In the global vocabulary of political science, the concept of a power grab evokes vivid and unmistakable images: tanks rolling through city streets, presidential palaces being stormed, and generals proclaiming martial law on national television. It is traditionally understood as an event, a violent rupture in the political fabric, an overt and extra-constitutional seizure of power. In his searing 2021 investigative work, The Silent Coup: A History of India’s Deep State, Josy Joseph presents a chillingly different, and arguably more insidious, narrative of democratic subversion.

Josy Joseph is a journalist and author. He used to be Security affairs correspondent of the Indian English daily Hindu , journalist with Malayalam portal Azhimukham and a founder of ‘Confluence Media’, a platform-agnostic investigative journalism organisation. He is an adjunct faculty at ‘O. P. Jindal Global University’. He challenges this conventional understanding, arguing that the Indian state, long overstated for a supposed robust civilian control over a its military, has been undergoing a “silent coup”—one that is not event-based but procedural, not military but bureaucratic, and executed not by suspending the Constitution but by systematically hollowing it out from within.

Joseph’s central thesis posits that a powerful, largely unaccountable “deep state,” composed of India’s non-military security and intelligence establishment, has been progressively weaponised by successive political executives. This process, he contends, has served to dismantle democratic norms, criminalise dissent, and consolidate power, pushing the “world’s largest democracy” towards a dangerous form of electoral authoritarianism. This is not a conspiracy theory of a shadow government, but a meticulously documented analysis of how the legitimate instruments of state security have been repurposed for political ends. The coup is “silent” because it operates under the veneer of legality, using the established machinery of the state — the police, federal investigative agencies, and intelligence bureaus — to achieve fundamentally anti-democratic objectives.

This article seeks to make a hermeneutic analysis of the key arguments presented in The Silent Coup. It attempts to interpret and synthesise Joseph’s multifaceted arguments by exploring four core pillars of his thesis. First, I would try to deconstruct Joseph’s delineation of this “silent coup” and the anatomy of the deep state that executes it. Second, I would analyse his argument that the politicised “war on terror” has served as the primary incubator for the deep state’s impunity and its most corrosive practices. Third, I would examine the systemic xenophobic bias that, according to Joseph, provides the ideological fuel for its discriminatory actions. Finally, I try to explore his conclusion that the resultant decay of institutional integrity — co-optation of media, deference of judiciary, and compliance of bureaucracy — completes the framework of this silent, ongoing subversion.

The Silent Coup is more than a work of journalism; I find it to be a profound political treatise that offers a vital theoretical framework for understanding the nature of democratic backsliding in the 21st century CE, where the architecture of the state itself becomes the primary tool of its own undoing.

Deconstructing “Silent Coup”

Josy Joseph’s most significant theoretical contribution is his reframing of the principal threat to Indian democracy. He decisively shifts the analytical focus away from the military barracks and into the labyrinthine corridors of power in New Delhi, locating the danger within the very institutions constitutionally mandated to protect the republic. This is not a future threat, but a present reality. The book’s jacket starkly declares the premise: “You do not need a military coup to subvert democracy… In India, it has already been subverted” (jacket of the book). This subversion is insidious precisely because it is silent; it eschews the drama of a violent takeover in favour of a quiet, procedural corrosion that leaves the façade of democratic institutions intact while eviscerating their substance.

The actors in this silent coup are not soldiers in fatigues but civil servants in formal attire, police officers in khaki, and intelligence operatives in the shadows. Josy Joseph meticulously identifies the key components of this deep state, viz., Intelligence Bureau (IB), India’s overarching domestic intelligence agency; Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), its external intelligence counterpart; Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), a politically compromised body; the National Investigation Agency (NIA), a post-26/11 creation to combat “terror”; and Enforcement Directorate (ED), which is mandated to investigate financial ‘crimes’ and has become the favoured tool for harassing political opponents. These agencies, Joseph argues, have undergone a dangerous mutation. They have transitioned from being professional bodies into becoming “storm-troopers” for the political executive of the day (p.7). Their primary operational mandate has, subtly but surely, shifted from protecting the public to securing the regime.

The sheer scale of this non-military establishment is a crucial element of Joseph’s analysis, transforming the concept of a “deep state” from a small, conspiratorial cabal into a sprawling, bureaucratic behemoth. As he quantifies, “There are about four million members in the non-military security establishment distributed across the country—from state police to tax collectors. In the seven decades since founding of the state of India, millions have suffered at the hands of the police; several families have been destroyed by intelligence agencies or fallen victim to motivated tax raids; thousands of under-trials await their turn at justice, many of them youngsters, who are thrown behind bars …; and rival politicians are caught in the crosshairs of a ruling regime’s ambitions. It is an endless vicious cycle.” (p.18) This quotation is not merely a statistic; it is a hermeneutic key to understanding the pervasive and systemic nature of the problem. Joseph is describing a Leviathan that is not hidden but operates in plain sight, its power touching the lives of ordinary citizens, activists, and political rivals through the mundane but terrifying processes of state action.

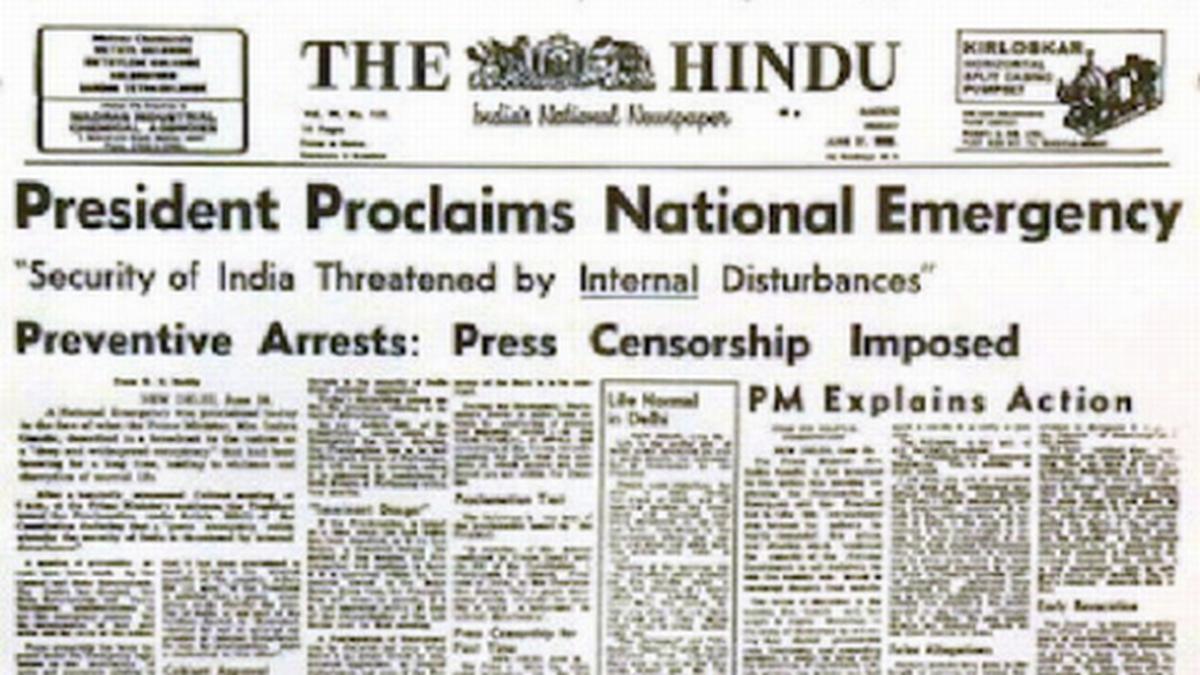

Crucially, Joseph is careful to present this as a systemic decay with a long history, not a recent phenomenon exclusive to one political party or alliance. He traces the origins of this systemic abuse through decades. It was, he asserts, the Congress party, particularly under the tenure of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, that “sketched the blueprint to manipulate the security establishment for political gains” (p.34). The ‘Emergency’ period (1975-77) was a dress rehearsal, a moment when the state’s coercive apparatus was openly and brazenly used to crush all opposition. However, Joseph’s critical insight is that what was once an episodic, overt abuse of power has, over time, become a normalised, systemic, and covert feature of Indian governance. He argues that while the Congress party may have laid the foundation, the BJP government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has perfected, scaled, and industrialised this model, integrating it into the very architecture of the state as a default mode of operation.

The methodology of this silent coup is procedural, its most potent weapon being the law itself. It involves the selective application of draconian statutes, launching of politically motivated investigations, pervasive use of surveillance to intimidate and blackmail, and cultivation of a climate of fear that chills free speech and dissent. In one of the book’s most memorable and chilling phrases, Josy Joseph asserts, “The process is the punishment” (p.152). An activist, a journalist, or a political opponent need not be convicted of a crime to be neutralised. The ordeal of a prolonged investigation — replete with early morning raids on their home, seizure of personal devices, freezing of bank accounts, and endless, financially draining court appearances — is sufficient to break their spirit, bankrupt their resources, and delegitimise them in the public eye. The deep state’s power, therefore, lies not in its ability to secure convictions — ED, for instance, has a notoriously low conviction rate — but in its immense capacity to harass and silence any voice deemed inconvenient to the ruling establishment. This systematic hollowing out of due process, Joseph contends, is the very essence of the silent coup, a subversion far more difficult to identify and counter than an open military takeover because it maintains the comforting, yet deceptive, façade of a functioning democracy.

War on Terror: Incubator of Impunity and Fabrication

Central to Joseph’s thesis is the argument that India’s long, complex, and often brutal “war on terror” has served as the primary incubator for the deep state’s institutional overreach and its most corrosive practices. Faced with intractable ‘insurgencies’ in Punjab, Kashmir, and Northeastern states, and series of devastating urban bomb blasts, the Indian security establishment, he argues, was pressured by both political masters and a fearful public to deliver results. In this high-pressure environment, it increasingly adopted “sinister solutions” to demonstrate efficacy (p.45). These solutions included fabricating evidence, staging fake “encounters” (extrajudicial killings), and, in some of the most damning allegations, even creating fictitious organisations to later claim credit for dismantling them. Over time, Joseph posits with grim irony, “militancy became a flourishing, multi-faceted business enterprise” (p.61). It morphed into an industry fuelled by vast, unaccountable funds, political imperatives for spectacular headlines, and the personal ambitions of careerist officers, where success was measured not by justice delivered but by enemies neutralised and narratives controlled.

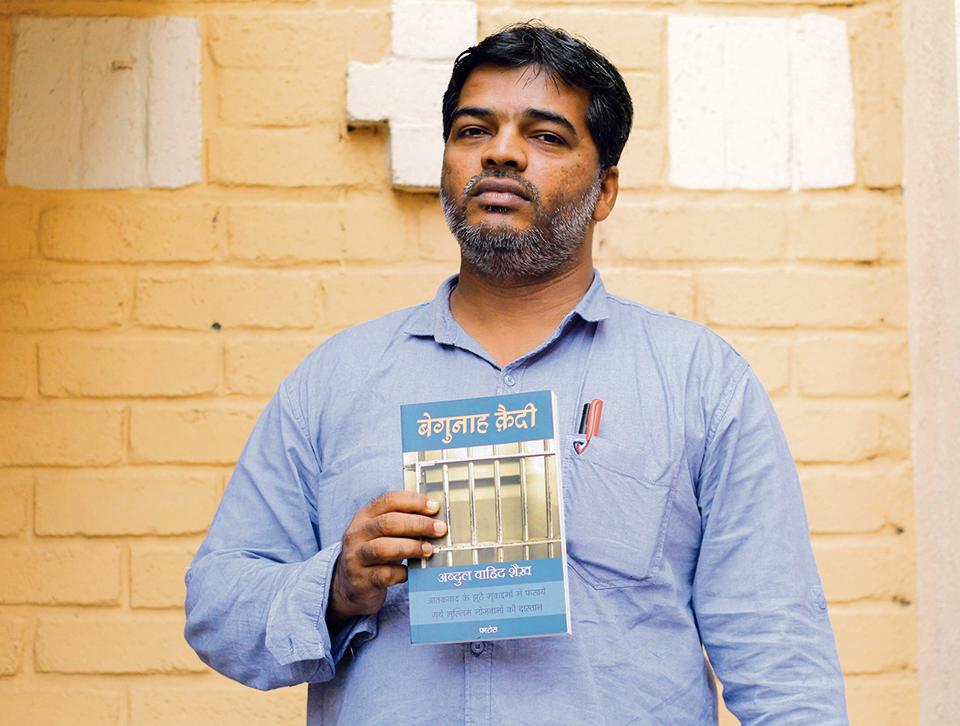

The book’s overarching narrative is framed by the harrowing ordeal of Wahid Sheikh, a Mumbai schoolteacher who serves as the human face of the system’s pathology. Sheikh was repeatedly arrested, systematically tortured, and implicated in a series of terror cases, including the 2006 Mumbai train bombings, before eventually being acquitted by the courts after years of imprisonment. Joseph uses his story as a microcosm to illustrate a chillingly cynical model employed by security agencies. He quotes an inside source who explains the grotesque logic: “It was a simple plan – create a fake ‘terrorist’, arrest him, ruin his life and show him off to the public as a success of the war on terror. This model, of creating a fake incident or a fake ‘terrorist’, is among the dirty secrets of the Indian security establishment” (p.162). This model is sustained by a deep-seated culture of impunity and a set of unprofessional, often illegal, investigative techniques. Joseph details the widespread use of torture to extract confessions and the reliance on dubious “deception-detection tests” like narco-analysis, which have been widely discredited by the scientific community. He describes how Wahid’s narco-analysis session was allegedly manipulated, with his drugged answers selectively edited to fit a pre-written confession. Joseph writes, “What Wahid went through, and complained about to the court, was yet another dark secret of India’s criminal justice system. There are several questions over the scientific accuracy of deception-detection tests… and the debate continues” (p.88). In the hands of a determined and unaccountable agency, these pseudo-scientific methods become powerful tools for manufacturing “evidence” to legitimise politically motivated arrests and secure convictions based on falsehoods.

The breakdown of professional ethics extends to the very foundations of intelligence gathering. Joseph provides a startling anecdote that reveals a frightening level of incompetence bred by a system that prioritises headlines over facts. “One time, central intelligence agencies received, and issued an alert for, a threat on the pilgrimage site of Sabarimala in Kerala, creating a public furore. Soon enough, though, a vigilant IB official established that a police inspector of the state Special Branch had received the information from one of his relatives, who also happened to be his paid informant. The IB official got the informant’s number and called him. The surprise call gave the man no time to prepare, and he blurted out: ‘I saw the threat in my dreams.’” (p.28-29) This almost farcical incident serves a serious hermeneutic purpose. It demonstrates how, within the deep state’s echo chamber, unsubstantiated information, rumour, and even dreams are laundered to formal intelligence alerts, creating public panic and justifying further state action. It points to a systemic rot where the mechanisms for verification have collapsed under the weight of a culture demanding constant threat narratives.

This operational decay is enabled and codified by a legal framework of exceptionally draconian ‘anti-terror’ laws. Joseph meticulously lists them and their impact, showing how the state has armed itself with instruments that dispense with the normal requirements of due process. “Since ‘Independence’, India has struggled with ‘insurgencies’ and, more recently, with ‘terror’. The result has been a state that reacted with increasingly draconian ‘anti-terror’ laws. The list of such legislations is very long… The collective output of these laws is staggering. For example, under TADA, at least 76,000 people were detained… 95 per cent of the trials under TADA ended in acquittals. Thus, the law had an overall conviction rate of less than 1.5 per cent… According to data presented in the Rajya Sabha in February 2021, only 2.2 per cent cases filed under UAPA between 2016 and 2019 ended in convictions. Almost 2,000 people were arrested under the law during this period.” (p.113-114) This detailed quotation provides the empirical backbone for Joseph’s “process is the punishment” thesis. The abysmal conviction rates are not a sign of the laws’ failure, but of their true purpose. They are not designed to secure just convictions but to enable the state to detain, harass, and neutralise individuals for years, effectively punishing them without a guilty verdict. The UAPA (Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act), in particular, with its stringent bail conditions, has become the deep state’s weapon of choice against activists, students, and dissenters, trapping them in legal limbo. The weaponisation of the counter-terrorism apparatus has thus had a devastating impact. It has not only destroyed countless innocent lives but has also, paradoxically, weakened India’s actual security by diverting vast resources towards fabricating cases and away from genuine intelligence gathering and professional policing.

Xenophobic Core: Systemic Bias and Targeting of Minorities

If “war on terror” provided the operational framework for deep state’s expansion, Joseph argues that a deep-seated xenophobic bias, specifically an institutionalised prejudice against India’s vast Muslim minority, provides its ideological fuel. He contends that the Indian security establishment, far from being a neutral arbiter of law, is afflicted with an “ingrained anti-Muslim prejudice” (p.112). This bias, he demonstrates, is not merely the sum of individual bigotries but is a structural feature of the system, manifesting in two interconnected and mutually reinforcing ways: the systemic and shocking underrepresentation of Muslims within the security forces, and the consequential, disproportionate targeting of the community in ‘counter-terrorism’ operations.

Joseph presents stark data to substantiate this claim of a demographic deficit that fosters an institutional echo chamber. The “High-Level Committee on Social, Economic and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India”, headed by Justice Rajinder Sachar, found that just over 3 percent of the paramilitary force was Muslim. Only 3 percent of the Indian Administrative Service was Muslim.” (p.25) Elsewhere, he notes the minuscule percentage of Muslims in police forces across various states where they form a significant part of the population, such as “2.3% of sub-inspectors in Uttar Pradesh” and just “1% of the Maharashtra state police” (p.115). Interpreted hermeneutically, these numbers are not just statistics; they are evidence of a structural exclusion that has profound consequences. This imbalance creates a mono-cultural security apparatus where prejudice can flourish unchecked, leading to a default institutional worldview where, as Joseph puts it, “‘right-wing Hindutva bombers never existed… [but] there were Muslims plotting against the nation everywhere'” (p.114).

This institutional bias inevitably translates into operational bias. Joseph meticulously documents a recurring pattern where, in the aftermath of a bomb blast, the default, almost pavlovian, response of investigative agencies is to round up dozens of local Muslim youth, often without a shred of credible evidence. These mass arrests serve an immediate political purpose: they project an image of swift, decisive action and placate a public and media baying for blood. The individuals caught in this dragnet, like Wahid Sheikh, become disposable pawns in a larger political game. Their lives are irrevocably damaged, they are publicly branded as terrorists, and they often spend years, sometimes decades, languishing in prison before being unceremoniously acquitted for lack of evidence. The damage, however, is already done.

This ingrained prejudice creates a fertile ground for the kind of false narratives and institutionalised Islamophobia that Joseph sees as a core feature of the deep state’s mindset. He argues that this is not a passive bias but an active, self-perpetuating cycle of misinformation. “A member of the Indian security establishment is often brought up on fake narratives about Islam, half-baked analyses and an environment that is actively hostile to Muslims. More often than not, it is the most Islamophobic voices that jump in with twisted narratives, eager to find Muslim perpetrators to a crime at hand. There is such a build-up of false narratives and fake stories that the security establishment and mainstream media are floating in fake information, wrong claims and a frightening level of Islamophobia.” (p.30) This passage connects the institutional structure to its ideological output. The lack of internal diversity (as shown by the Sachar Committee data) allows these fake “narratives” to circulate and solidify into operational “truths”, creating a system that is primed to see Muslim perpetrators behind every incident.

Joseph powerfully contrasts this aggressive and often fabricated pursuit of Muslim suspects with the establishment’s conspicuous reluctance and even sabotage of investigations involving Hindu elements. He details how probes into major bomb blasts perpetrated by Hindutva groups, such as the Samjhauta Express, Mecca Masjid, and Malegaon blasts, were often slow-walked, undermined, or allowed to collapse as key witnesses turned hostile under mysterious pressure. This glaring dual standard, he argues, is not accidental or incidental. It is a core feature of the silent coup, which seeks to align the state’s formidable coercive power with a majoritarian political project. The consequences of this xenophobic security policy are profound and devastating. It deepens the alienation of India’s largest minority community, systematically erodes their faith in the impartiality of the state, and, in a tragic irony, creates a genuine grievance that could become fertile ground for actual radicalisation. By treating an entire community of over 200 million people with suspicion, the deep state not only perpetuates grave injustice on an industrial scale but also critically undermines social cohesion, a foundational component of true national security.

The Decay of the Republic: Erosion of Institutional Checks and Balances

The silent coup, as described by Josy Joseph, is a parasitic enterprise; it can only thrive by weakening its host. The final sections of his book paint a grim but coherent picture of this systemic decay, where the deep state’s influence extends beyond its own ranks to compromise, co-opt, or intimidate the other institutional pillars of democratic process designed to hold executive power accountable. Judiciary, media, and bureaucracy, in Joseph’s analysis, have, in large part, either been enlisted as partners in the subversion or have abdicated their professional roles, creating a self-reinforcing ecosystem of authoritarian control.

Joseph reserves some of his sharpest and most sorrowful criticism for the Indian mainstream media, an institution he knows intimately. He argues that a vast and influential segment of the mainstream media, particularly the cacophonous world of television news, has disastrously abandoned its watchdog function to become a “cheerleader for the government” and a willing, uncritical amplifier of the deep state’s narratives (p.215). In this corrupted information ecosystem, unsubstantiated leaks from anonymous agency sources, baseless accusations against government critics, and manufactured intelligence reports are laundered through pliant media channels and presented to the public as established, verified facts. Journalists who dare to question the official narrative or conduct independent investigations are harassed, intimidated, sued, and targeted with retaliatory investigations by the very agencies they seek to hold accountable. The media, in this formulation, is no longer a “fourth pillar of democracy” but an essential partner in the silent coup, tasked with the crucial functions of “manufacturing consent and legitimising the state’s excesses” (p.216).

The judiciary, long considered the ultimate bulwark against executive overreach in India, has also, in Joseph’s disquieting view, shown signs of a troubling deference to the state, particularly in recent years. He identifies a pattern of judicial decisions where the courts appear to prioritise the state’s often-vague claims of “national security” over the fundamental rights of citizens. This is exemplified by the increasing judicial acceptance of evidence submitted by agencies in “sealed covers,” a practice that denies the accused the basic right to see or rebut the allegations against them, making a mockery of the principles of natural justice. This, combined with a general reluctance to grant bail in cases filed under draconian laws, like UAPA, effectively allows the executive to indefinitely incarcerate its critics. Joseph argues that in many crucial cases, “the courts have often looked the other way, or worse, sided with the executive” (p.189). While he is careful to acknowledge that pockets of courageous judicial resistance remain, the overall trend he documents points towards a judiciary that is increasingly unwilling or unable to effectively check the untrammelled power of the deep state.

This institutional erosion is completed by what Joseph terms a “compliant bureaucracy” (p.88). Motivated by a combination of fear of punitive transfers or career stagnation, and the promise of lucrative post-retirement sinecures, many civil servants have, according to his analysis, abandoned their professional mandate to uphold the rule of law. Instead, they choose the path of least resistance, faithfully serving the political executive’s will, no matter how partisan or legally dubious. They become the quiet, unassuming facilitators of the silent coup, subverting established processes and enabling the capture of institutions from within their own ranks.

This trifecta of a compromised media, a deferential judiciary, and a pliant bureaucracy creates a formidable, near-impenetrable environment where the deep state can operate with almost total impunity. The “stubborn refusal to hold anyone in the security world accountable” is a recurring lament in the book (p.240). Officers who fabricate evidence, torture suspects, or stage extrajudicial killings are rarely, if ever, punished. More often, they are rewarded with promotions, gallantry medals, and public praise, sending a clear and chilling signal throughout the system: loyalty to the political regime will be protected and rewarded, while adherence to constitutional principles and due process is a professional liability. This, Joseph concludes, is the final and most dangerous stage of the silent coup, where the entire institutional framework of the republic is systematically repurposed to serve a creeping authoritarian agenda, all while maintaining the outward appearance of a constitutional democracy.

A Republic on the Brink

Josy Joseph’s The Silent Coup: A History of India’s Deep State is a monumental and deeply unsettling work of investigative journalism that transcends mere reportage to offer a powerful and disturbing political theory for our times. It is a meticulous chronicle of how a vibrant, noisy democracy was dismantled not with a single, decisive blow, but through a thousand procedural cuts, administered silently and relentlessly by the very hands sworn to protect it. The book’s central arguments — that a non-military deep state has been weaponised by the political class; that “war on terror” has been used as a pretext for fabricating evidence and normalising impunity; that this entire system is fuelled by a deep-seated, structural xenophobic bias; and that it has been enabled and sustained by decay of other democratic institutions — combine to form a compelling, coherent, and chillingly persuasive thesis.

Joseph’s work serves as a powerful indictment of the Indian establishment that cuts across party lines, arguing that the silent coup is the bitter fruit of decades of systemic rot, which has now been dangerously accelerated and institutionalised. He makes it clear that merely changing the government at the ballot box will not suffice to remedy the ailment. The problem he diagnoses is not just political; it is profoundly structural. What is required, he implicitly suggests, is a fundamental reform of the entire security apparatus, establishment of robust and independent accountability mechanisms, and a renewed, fierce commitment from all pillars of the state — and society — to the foundational principles of constitutional democracy.

Ultimately, The Silent Coup is a vital and urgent warning. It is a clarion call to citizens, scholars, and jurists to recognise the subtle, insidious nature of modern authoritarianism, which often cloaks itself in the comforting language of national security and the mundane procedures of law. Josy Joseph’s meticulous documentation and concerned analysis provide a definitive, if terrifying, account of the architecture of systemic subversion in contemporary India. He makes it devastatingly clear that the greatest threat to the Indian republic may not come from external enemies or uniformed generals, but from the shadowy Leviathan within, a deep state that is methodically and silently executing a coup against the public. The scholarly value of The Silent Coup lies in its masterful, hermeneutical achievement: it teaches us how to listen for the silence that precedes a state’s death, making audible the quiet, procedural grinding of the gears as a republic is hollowed out from the inside.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.