Freedman, Russell. The War to End All Wars: World War I. New York: Clarion Books, 2010.

Russell Freedman’s The War to End All Wars: World War I is a non-fiction work that offers a comprehensive, yet highly accessible, exploration of the pivotal conflict of the early 20th century. Primarily aimed at young adult readers, Freedman transcends the typical boundaries of the genre. With its clear, engaging prose, abundant archival photographs, and powerful primary source accounts, the book stands as a testament to Freedman’s skill in rendering complex historical events comprehensible and emotionally resonant. Freedman, is a recipient of the Newbery Medal and celebrated for his historical narratives such as Lincoln: A Photo-biography. The book, comprising 192 pages and published by Clarion Books in 2010, is not an exhaustive academic to me, but rather a thoughtfully curated and dynamically presented overview. It succeeds in balancing the grand geopolitical forces that propelled the world into war with the intimate, harrowing experiences of those who lived—and died—through it. Dedicated to his father, who served in France during the war, there is an underlying personal resonance, though without compromising objectivity. This is a sobering, educational, and unflinching account that solidifies its place as a stand-out in historical literature.

One of the book’s foremost strengths lies in Freedman’s exceptional ability to humanize the “Great War” without oversimplifying its immense complexities. He skillfully interweaves official histories and strategic overviews with vivid first-hand accounts—culled from soldiers’ diaries, letters, and memoirs—to illustrate the initial patriotic fervor, its rapid dissolution, and the profound disillusionment that followed. The book is richly illustrated with over 100 black-and-white archival photographs, maps, and period posters. These visuals are far more than mere decorations; they serve as a “moving visual counterpart” (as often noted by critics), adding a visceral and immediate dimension to the often abstract horrors of combat and trench life.

The narrative unfolds chronologically and thematically across fifteen chapters, guiding the reader from the geopolitical tensions preceding the war to its flawed conclusion and enduring legacy. Freedman commences by painting a detailed picture of Europe in the early 20th century, a continent outwardly at peace, prosperous, and interconnected through international trade and royal lineage, yet simmering with deep rivalries. He meticulously unpacks the underlying forces of burgeoning nationalism, aggressive militarism, and entangled imperial ambitions, all of which contributed to an increasingly fragile balance of power. Germany’s post-1871 unification and its ambitious naval expansion, coupled with France’s resentment over Alsace-Lorraine and Russia’s expansionist aims, are presented as critical elements in the escalating arms race and the formation of competing military alliances: The Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy) and the Triple Entente (France, Russia, Britain). This intricate web of pacts meant that a localized conflict had the potential to ignite a continental, and then global, conflagration.

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie by Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, is presented as the critical spark that ignites this powder keg, rather than the singular cause. Freedman meticulously details how Austria-Hungary’s punitive ultimatum to Serbia, backed by Germany, triggered a fatal chain reaction. Russia mobilized to support Serbia, compelling Germany to mobilize against both Russia and France, leading to declarations of war in rapid succession. Germany’s controversial invasion of neutral Belgium, a key component of its Schlieffen Plan to swiftly defeat France, then prompted Great Britain to declare war, thus drawing all major European powers into the conflict.

Early chapters vividly capture the initial euphoria and widespread, albeit tragically naive, expectation of a short, glorious victory. Soldiers marched off to war amidst cheers and nationalist fervor, convinced they would be home by Christmas. Freedman sharply contrasts this optimism with the brutal reality that quickly emerged on the battlefield. The introduction of modern weaponry—such as long-range artillery, rapid-fire machine guns, and elaborate barbed wire defenses—rendered traditional cavalry charges and open-field assaults suicidal. These technological advancements, rather than ensuring a swift victory, led to unprecedented casualty rates and the rapid devolution of the war into a deadly stalemate. Freedman illustrates this with stark figures, noting the staggering 100,000 men killed in the first month alone, and over 600,000 on the Western Front by the end of 1914. The core of the book delves into the infamous stalemate of trench warfare along the Western Front, stretching an unbroken 475 miles from the English Channel to the Swiss Alps. Chapters like “Life and Death in the Trenches” graphically depict the monotonous, terrifying, and squalid daily existence endured by soldiers. Freedman uses powerful, unvarnished quotes from soldiers’ letters and diaries to convey the visceral reality of mud, rats, lice, disease (like trench foot and trench mouth), and the omnipresent stench of decay and overflowing latrines. “No man’s land,” the desolate expanse between opposing trench lines, is portrayed as a desolate killing field, crossed only at immense cost during “over the top” offensives that frequently yielded minimal gains for catastrophic losses.

Freedman recounts the appalling nature of major battles with harrowing detail, focusing on their human cost rather than just strategic maneuvers. The First Battle of the Marne, a chaotic engagement where Parisian taxis rushed reinforcements to the front, is presented as the “Miracle of the Marne” that saved Paris and halted the initial German advance, leading directly to the digging of the first trenches. The German assault on Verdun in 1916, intended as a “war of attrition” to “bleed France white,” is meticulously detailed, showcasing the sheer pulverization of the landscape and the half-million casualties suffered by both sides. Similarly, the British-led offensive on the Somme, launched to relieve pressure on Verdun, resulted in the bloodiest day in British military history on July 1, 1916, with over 20,000 killed or missing and 40,000 wounded, for negligible territorial gains. These accounts are punctuated by soldier testimonials, such as the haunting report of a British officer near Ypres, who “had to argue with many of them as to whether they were dead or not” after a gas attack.

“The Technology of Death and Destruction” explores the continuous innovation driven by the stalemate. Poison gas, first introduced by Germany at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, added a new dimension of terror and suffering, causing suffocation, blindness, and agonizing blisters. Tanks, initially clumsy but terrifying to German troops when deployed by the British in 1916, would evolve into a significant offensive weapon by 1918. Aviation rapidly transitioned from reconnaissance to aerial combat (“dogfights”) and bombing, creating new heroes like Germany’s Red Baron and America’s Eddie Rickenbacker.

Freedman also broadens the scope beyond the Western Front, though acknowledging its central importance. He discusses the vast and devastating Eastern Front, where Russia suffered immense losses against Germany and Austria-Hungary, ultimately leading to the collapse of the Csarist regime and the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. The catastrophic Gallipoli campaign in 1915, an Allied attempt to knock Turkey out of the war, is presented as another example of costly failure. The war at sea is covered through Britain’s naval blockade, which starved Germany, and Germany’s retaliatory unrestricted submarine warfare, most notably the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, which began to turn American public opinion against Germany.

The entry of the United States into the war in April 1917, spurred by Germany’s resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare and the Zimmermann telegram, is portrayed as the critical turning point that decisively shifted the balance of power in favor of the Allies. While America mobilized its relatively small army, the Allies faced severe setbacks in 1917, including French army mutinies and horrific British casualties at the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), where the battlefield dissolved into an impassable morass of mud. However, the eventual arrival of American “doughboys” at a rate of 120,000 per month bolstered Allied morale and forces, proving their mettle at engagements like Château-Thierry and Belleau Wood, and playing a crucial role in halting the final German offensive in 1918.

The war’s conclusion in 1918 is presented with clarity, detailing Germany’s “Last Offensive” under General Ludendorff, its initial successes, and its eventual collapse under sustained Allied counter-attacks, including the significant Meuse-Argonne campaign involving American forces. The surrender of Germany’s allies, and revolutionary outbreaks within Germany itself, led to Kaiser Wilhelm II’s abdication and the signing of the armistice on November 11, 1918.

Freedman concludes with a sombre assessment of the war’s staggering human cost—65 million men mobilized, 8.5 million killed, 21 million wounded, and millions more civilians lost to famine and disease. The final section, “Losing the Peace,” critically examines the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919. Dominated by the punitive demands of France’s Clemenceau, the treaty placed sole responsibility for the war on Germany, imposing crippling reparations, territorial losses, and severe military restrictions. Freedman powerfully argues that these harsh terms—the “war guilt” clause, the economic burden, and the national humiliation—created deep resentment and instability in Germany, directly setting the stage for the rise of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist (Nazi) party, and ultimately leading to World War II. French Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch’s prescient declaration, “This is not peace. It is an armistice for twenty years,” encapsulates the tragic irony.

“Cheating of Sharif Husain” and the Deliberate Division of Muslims

Russell Freedman’s “The War to End All Wars” masterfully illuminates the intricate and often duplicitous machinations of the Allied powers, particularly Britain and France, during World War I. While ostensibly a global conflict, the war served as a pivotal moment for imperial ambitions, nowhere more evident than in West Asia. Freedman meticulously details how the British deliberately deceived Sharif Husain of Makkah with conflicting promises, simultaneously orchestrating a grander imperial project to dismantle the Ottoman State and create lasting divisions among Muslims by fostering artificial nationalisms. This calculated strategy ensured that a unified Arab or Muslim power would not emerge, securing Western dominance for decades to come.

Freedman presents the British relationship with Sharif Husain of Makkah as a stark narrative of deliberate deception, driven by wartime expediency and entrenched imperial ambition. He meticulously outlines three crucial and contradictory British promises that ultimately formed the foundation of this betrayal.

Promise to Arabs (Husain-McMahon Correspondence)

By 1915, the war in West Asia had devolved into a costly stalemate, marked by significant Allied setbacks, notably the disastrous Gallipoli campaign. In search of a new avenue to undermine the Ottoman State, which was allied with Germany, the British turned their attention to the potent force of Arab nationalism. Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, initiated a secret correspondence with Sharif Husain bin Ali, the Ottoman Governor of the Hejaz Province, which contained the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah.

Freedman elaborates on McMahon’s enticing offer: if Husain would launch an Arab revolt against the Ottoman army, Great Britain would support the creation of a vast, independent Arab state after the war. This proposed state would encompass the overwhelming majority of the Arab-speaking lands of the Ottoman State, with only vaguely defined coastal areas excluded. Freedman underscores the hope this promise ignited among many Arab leaders.

Believing implicitly in the British pledge, Sharif Husain ignited the Arab Revolt in June 1916. Arab forces, bolstered by the legendary British liaison T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”), waged a remarkably effective guerrilla campaign against Ottoman forces. They captured strategically vital ports and relentlessly disrupted Ottoman supply lines, playing an indispensable role in the eventual Allied triumph in the region.

Secret Betrayal (Sykes-Picot Agreement)

Freedman’s narrative takes a dark turn as he reveals the simultaneous and cynical deception at play. Even as McMahon was extending promises of independence to the Arabs, Britain was secretly negotiating a clandestine pact with its primary ally, France. In 1916, Mark Sykes, representing Britain, and François Georges-Picot, representing France, literally drew lines across a map of West Asia, carving up the very lands that had been pledged to the Arabs.

Sykes-Picot Agreement, as Freedman explains, proposed a starkly different post-war reality. France was to acquire direct control over modern-day Syria and Lebanon. Britain, in turn, would seize control of Iraq and Jordan, alongside a special sphere of influence in Palestine. The envisioned independent Arab state, so grandly promised to Husain, was effectively shrunk to a small, landlocked territory in the interior.

Freedman articulates about this unequivocal and cynical betrayal. The British harbored no genuine intention of honoring their commitment to Husain. Instead, they strategically exploited the Arab Revolt as a powerful tool to weaken and defeat the Ottomans, all the while secretly planning to divide the spoils with the French. The Arabs were fighting for a unified independence that the British had already, in secret, decided to deny them.

Third Promise (Balfour Declaration)

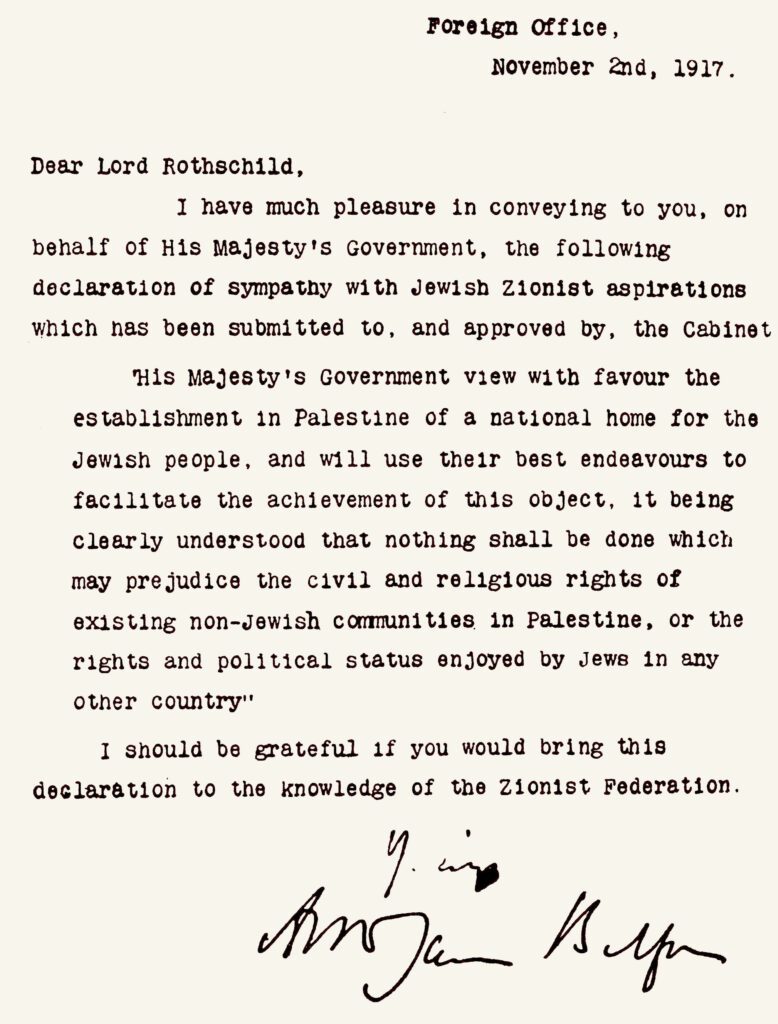

To compound the layers of deception, Freedman introduces the Balfour Declaration of 1917. In this public statement, the British government declared its support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”

This promise, made to the international Zionist movement, directly contradicted the earlier assurance given to Sharif Husain that Palestine would be an integral part of his independent Arab state. Furthermore, it also clashed with the Sykes-Picot plan, which had designated Palestine as an internationally administered zone. Freedman makes it clear that this declaration, too, was not born of altruism but was a calculated geopolitical move to garner Jewish support for the Allied war effort.

In essence, Freedman portrays the “cheating of Sharif Husain” not as an accidental oversight or an unfortunate by-product of war, but as a meticulously calculated British policy. It was a strategy of telling three different groups three fundamentally different things to secure their crucial support during the war, with absolutely no intention of honoring all of these conflicting commitments.

Imperialist Project of Creating Divisions

Freedman explicitly links these broken promises to a much broader and more insidious imperial strategy: the permanent dismantling of the Ottoman State and its replacement with a fragmented, easily controllable region. This was the essence of the classic “divide and rule” policy, strategically applied to shatter Muslim unity.

Fomenting Nationalism as a Weapon

The book explains that the British astutely recognized the immense power of nationalism. The Ottoman State was a vast, multi-ethnic, and multi-religious state, whose cohesion was largely maintained by the authority of the Sultan-Caliph in Istanbul. The British identified that by actively encouraging and arming burgeoning nationalist sentiments, they could provoke the empire’s collapse from within.

The ultimate division the British ruthlessly exploited was that between Arabs and Turks. They aggressively promoted the concept of “Arabism” and the vision of an independent Arab future to incentivize Arab leaders to break away from the Turk-led Ottoman state. T.E. Lawrence was instrumental in this strategy on the ground, personally reassuring Arab leaders of British support and skillfully stoking their ambitions for independence.

Freedman also highlights the critical religious dimension of this strategy. The Ottoman Sultan held the revered title of Caliph, the spiritual leader of the Sunni Muslim world. By inciting an Arab revolt against the Caliph, the British were deliberately attempting to shatter the religious and political unity of the global Muslim community, thereby further debilitating their formidable enemy. Lawrence himself acknowledged this in an intelligence memo, stating the Arab revolt was “beneficial to us because it marches with our immediate aims, the break-up of the Muslim ‘bloc’ and the defeat and disruption of the Ottoman State.” The British Foreign Department of India even articulated this desire for “a weak and disunited Arabia, split up into little principalities… incapable of coordinated action against us.”

True to its intentions, Great Britain pulled the mat from under Sharif Husain’s feet once he declared Caliphate for himself. Sequential developments that were created by them, saw him being exiled and removed from power, until his death and burial in Jerusalem.

Creating Artificial States to Ensure Division

Freedman powerfully argues that the Sykes-Picot Agreement was far more than a simple division of spoils; it was the foundational blueprint for the post-war West Asia, specifically designed to create a new imperial order rather than liberate Arabs.

The borders arbitrarily drawn by Sykes and Picot were entirely artificial, paying no heed to the complex ethnic, tribal, and religious realities on the ground. For instance, they deliberately amalgamated Shiites, Sunnis, Arabs and Kurds into the new British mandate of Iraq.

Freedman elucidates the cynical imperial logic underpinning this strategy: a region populated by numerous small, weak, and internally divided states would be infinitely easier for Britain and France to control than a single, large, and unified Arab nation. These newly formed states would be perpetually dependent on their European “protectors” to maintain power and to manage their inherent internal conflicts. This guaranteed long-term Western influence and effectively pre-empted the emergence of any indigenous regional power capable of challenging European dominance. As Lawrence observed in a secret memorandum, there was an urgent need “to divide Islam.”

Russell Freedman’s “The War to End All Wars” unequivocally presents the British actions in West Asia as a masterful demonstration of cynical imperial strategy. “Cheating” of Sharif Husain was not an accidental or unfortunate by-product of the war; it was, in fact, the central tactical maneuver within a much larger and deliberate imperial project.

The British strategy can be summarized as follows:

Use ‘Nationalism’: Encourage Arab ‘nationalism’ to effectively weaponize Arabs against Ottomans.

Betray ‘Nationalists’: Secretly conspire with allies to divide the very lands promised to these partisans.

Create Divisions: Draw artificial borders that forcibly group rival ethnic, tribal, and religious communities into new, often contentious states and also divide the same ethnicities, language communities and tribes into rival entities in the process, thereby ensuring their inherent weakness and dependence on imperial patronage.

Secure Control: The ultimate outcome is a thoroughly fractured West Asia, no longer unified under the Ottoman State, but now effortlessly susceptible to British and French political and economic domination.

Freedman concludes by highlighting the tragic and enduring legacy of this policy. The arbitrary borders and the fundamentally conflicting promises made during World War I sowed the deep seeds of conflict and instability that have, regrettably, plagued West Asia for over a century, continuing to shape its geopolitical landscape to this day. The “War to End All Wars” ironically laid the groundwork for countless conflicts to come, a stark testament to the profound and destructive impact of imperial ambition.

Freedman further explains the genesis of the “stabbed in the back” myth and the failings of the League of Nations: “The Allies had chosen to deal with officials of Germany’s newly formed Weimar Republic, leaving the German army uninvolved. The army now protested that it had never actually surrendered but had simply agreed to a cease-fire, and at the time of the armistice was still in possession of vast conquered territories. Former military leaders and their supporters sought to blame Germany’s defeat on cowardly and traitorous liberal politicians, rather than on the exhaustion of the German war machine. The army, they claimed, had been “stabbed in the back.” President Wilson was disappointed in his hope that the League of Nations would preserve world peace. Established by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, the League was beset with problems from the beginning. Germany was accepted as a member in 1926 and Russia joined in 1934, but ironically, even though Wilson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 1919, the United States refused to join the international organization. Once the war was over, many Americans felt that the country’s intervention in Europe had been a mistake, never to be repeated. Wilson travelled the United States, trying to win support for both the treaty and the League. But many senators were opposed to the treaty as written, and American isolationists wanted to keep the United States out of world affairs. Despite Wilson’s efforts, Congress failed to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. As a result, the United States, which had suddenly become the world’s most powerful country, never became a member of the League of Nations.” (p.164).

The book underscores how “the war to end all wars” tragically failed to achieve lasting peace, instead sowing the seeds for even greater global upheaval and defining the course of the century after that and beyond.

Major Themes and Strengths:

• Human-Centric: Freedman consistently prioritizes the experiences of individuals caught in the conflict. Through evocative quotes and personal accounts, he gives voice to the soldiers and civilians on all sides, fostering a deep emotional connect with the historical events.

• Visuals: The liberal use of over 100 carefully selected archival photographs, maps, and illustrations is a cornerstone of the book’s effectiveness. These visuals are integral to the storytelling, making the abstract horrors and realities of the war tangible and immediate.

• Clarity and Accessibility: Freedman possesses an exceptional talent for distilling complex geopolitical, military, and technological concepts to clear, concise, and engaging prose, making the book accessible to a broad audience, without sacrificing historical integrity.

• Historical Balance and Nuance: The book avoids jingoism or oversimplification, presenting a balanced view of the conflict. Freedman highlights the blunders and failures of leadership, the senseless waste of life, and the shared suffering of all combatants, while also acknowledging acts of courage and rare moments of humanity, such as the 1914 Christmas Truce.

• Focus on Legacy and Consequences: Perhaps the book’s most compelling aspect is its unwavering focus on the long-term impact of World War I. Freedman meticulously traces how the war’s unresolved issues, the flawed peace treaty, and the dissolution of empires directly contributed to the geopolitical landscape of the inter-war period and the eventual outbreak of World War II, making the historical narrative urgently relevant to understanding contemporary global dynamics.

Major Quote:

One of the most powerful passages, capturing the book’s overarching theme of the war’s senseless escalation and the initial misjudgment of its nature, comes from pages 18-19:

“And so Europe was caught up in a war that few had expected and almost no one wanted. Even today, historians continue to debate the tangled and confusing causes of the conflict, the series of accidents, blunders, and misunderstandings that swept the nations of Europe toward war in the summer of 1914, whether war might have been avoided, and which persons or nations were most responsible. Wars in the past had often been caused by countries seeking more land or natural resources, or acting out of suspicion and fear of their rivals. And once a country is fully armed and poised to attack, war, it seems, is hard to avoid.”

This quote encapsulates Freedman’s argument that World War I was a confluence of factors—accidental blunders, ingrained rivalries, and an unavoidable logic of mobilization—rather than a singular, easily attributable cause. It underscores the tragic inevitability once the intricate alliance system was triggered and nations were “armed to the teeth.”

Russell Freedman’s The War to End All Wars: World War I is an essential and deeply affecting work of historical non-fiction. It does far more than simply recount facts; it immerses the reader in the lived experience of the Great War, making its immense scale and profound tragedy both comprehensible and emotionally resonant. Freedman’s masterful storytelling, combined with meticulous research and powerful visual elements, renders a complex historical period accessible to young adults and compelling for general readers. This book serves as a vital reminder of the catastrophic costs of nationalism, militarism, and fractured diplomacy, and eloquently demonstrates why World War I remains a defining event, whose legacy continues to shape our current world. It is highly recommended for anyone seeking a powerful and enduring account of “the war to end all wars” that ironically paved the way for even greater global conflicts.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.