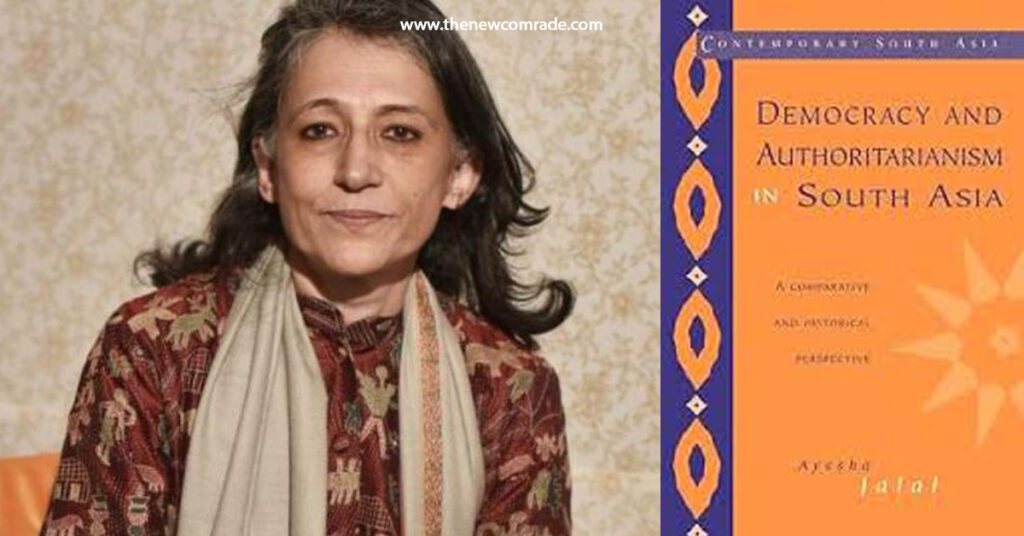

Ayesha Jalal, Democracy and Authoritarianism in South Asia: A Comparative and Historical Perspective, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995

Ayesha Jalal’s Democracy and Authoritarianism in South Asia: A Comparative and Historical Perspective, published in 1995, stands as a seminal intervention in understanding the complex and often contradictory political trajectories of post-colonial India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Esteemed for her rigorous scholarship and willingness to challenge established narratives, Ayesha Jalal, a distinguished historian at Tufts University with prior impactful works on modern South Asian political history and its dynamics, offers a nuanced analysis that moves beyond simplistic binaries. Her work commands attention not for providing comfortable answers but for reformulating the very questions we ask about state formation, political legitimacy, and societal conflict in the subcontinent.

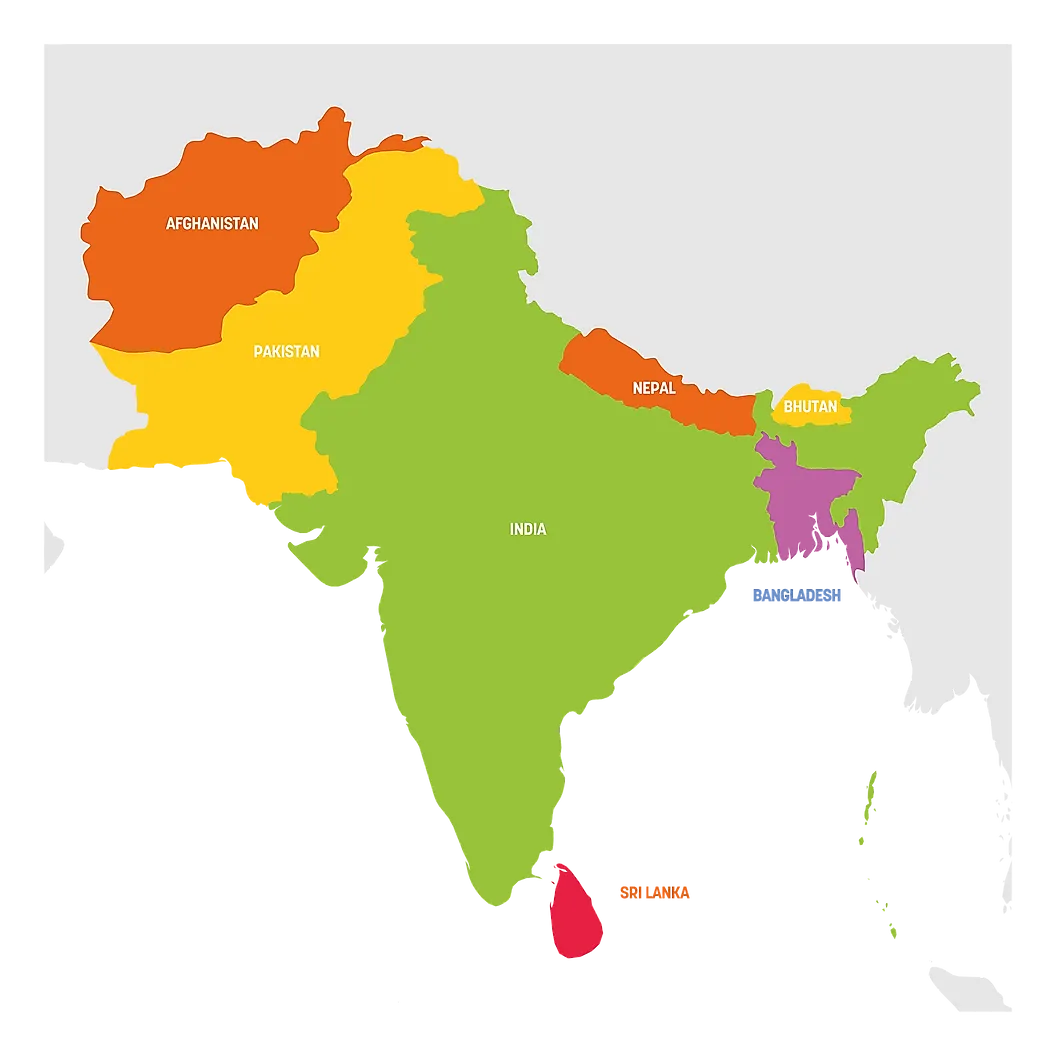

The book’s central, and perhaps most challenging, thesis is a direct refutation of the conventional wisdom that attributes the divergent political outcomes in South Asia — ’ostensible democracy’ in India versus ‘persistent authoritarianism’ in Pakistan and Bangladesh — solely to their shared British colonial legacy or inherent cultural dispositions. Instead, she argues that while formal political systems differed, the central political authorities in all three states faced remarkably similar threats. These included pressures from regional and linguistic dissent, religious and sectarian strife, and class and caste-based conflicts. Far from being mutually exclusive opposites, Jalal posits that democracy and authoritarianism in South Asia have been co-constitutive forces, often existing in a tense interplay, where democratic processes are used to legitimise centralised power and authoritarian measures are deployed to protect the so-called democratic state’s integrity.

The Great Rupture: Partition and the Shattering of a Subcontinental Unity

To fully grasp Jalal’s argument, one must first understand her framing of the 1947 Partition not merely as a political division but as a catastrophic severing of a deep, albeit flexible, historical unity. She contends that before the British consolidated their rule and imposed rigid administrative and census categories, South Asia possessed a rich tapestry of overlapping identities and political arrangements that allowed for accommodation. The idea of “India” as a geographical and civilisational space, she argues, long predated the colonial state. It was this historical fabric that Partition tore asunder with unprecedented violence.

Jalal eloquently captures this profound sense of historical disjuncture:

“Few political decisions in the twentieth century have altered the course of history in more dramatic fashion than the partition of India in 1947. To be sure, the end of formal colonialism and the redrawing of national boundaries was a tumultuous event, sending tremors throughout much of Asia and beyond. Yet perhaps nowhere was the shock felt more intensely or more violently than in the Indian subcontinent. Economic and social linkages, which over the millennia had survived periods of imperial consolidation, crises and collapse to weld the peoples of the subcontinent into a loosely layered framework of interdependence, were rudely severed. Political differences among Indians over the modalities of power-sharing, once independence had been won, sheared apart the closely woven threads of a colonial administrative structure that had institutionally integrated, if never quite unified, the subcontinent. That the culmination of some two hundred years of colonial institution-building should have sapped the subcontinent’s capacity for accommodation and adaptation is a telling comment on the ways in which imperialism impressed itself on Indian society, economy and polity. A rich and complex mosaic of cultural diversities which had evolved creative political mechanisms of compromise and collaboration long before the colonial advent, India through the centuries had managed to retain its geographical unity despite the pressures imposed by military invasion, social division and political conflict. There was little agreement on the basis of this unity or on its precise boundaries. Yet the idea of India as a distinctive geographical entity largely escaped the rigours of searching scepticism. Tracing its origins to the epic period in ancient Indian history, the concept of Bharat or Mahabharat had come to encapsulate a subcontinental expanse of mythical, sacred and political geography. Later the Arab and Persian exogenous definitions of Al-Hind or Hindustan, as the land beyond the river Sindh or Indus, became readily internalised and identifiable in the geographical lexicon of Indo-Islamic culture and civilisation. By and large the fluidity of the boundaries of geographical India were matched in the pre-colonial era by the flexibilities of political India.” (p.9)

This sweeping passage is foundational to Jalal’s entire thesis. By invoking pre-colonial concepts like Bharat and Hindustan, she views that South Asia’s identity was not a mere British creation but a long-standing, organic reality characterised by “flexibilities.” Her core critique here is aimed at the British colonial project, which, despite its “institutional integration,” ultimately destroyed the indigenous “creative political mechanisms of compromise and collaboration.” Partition, in this view, is the tragic endpoint of a colonial process that hardened identities and centralised power, making the pre-existing accommodative politics impossible. This framing allows Jalal to argue that the post-1947 states were all built upon this shared trauma and inherited a similar political DNA of conflict management through centralisation, regardless of whether they were formally “democratic” or “authoritarian”. The rupture was so total that it set the stage for the deeply insecure and over-centralised states that would follow.

Deconstructing the Partition Narrative and Divergent State Formation

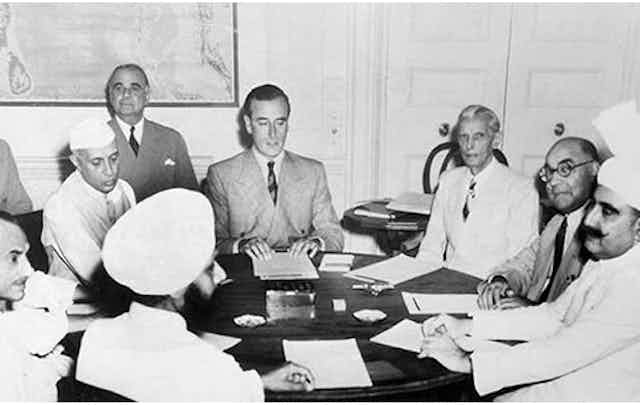

Jalal’s most significant contribution is her meticulous deconstruction of the political rationales that led to Partition. She moves beyond the simplistic story of the Muslim League’s “intransigent demand for a separate nation” and Congress’s “reluctant acceptance”. She argues that the final outcome — a “moth-eaten” Pakistan and a centralised Indian Union — was neither what the Muslim League had initially sought nor what Congress had “sorrowfully conceded”.

First, she reframes the Muslim League’s strategy under Muhammad Ali Jinnah. The famous 1940 Lahore Resolution, often cited as the definitive call for a separate state, was, in Jalal’s reading, a deliberately ambiguous and powerful bargaining tool. Its aim was to secure constitutional safeguards for Muslims within a united, but highly decentralised, confederal India. The real goal was not secession, but a reconfiguration of power that would give provinces significant autonomy.

“Designed to safeguard the interests of all Indian Muslims, the League’s communal demand for a Pakistan carved out of the Muslim-majority areas in the north-west and north-east of the subcontinent failed to contain the regionalisms of the Muslim provinces. These provinces lent support to the Muslim League in the hope of negotiating a constitutional arrangement based on strong provinces and a weak centre. This is why the Pakistan resolution of March 1940 had spoken of ‘Independent Muslim states’ in which the constituent units would be ‘autonomous and sovereign’. Jinnah had taken care to hedge this concession to Muslim-majority province sentiments. An unlikely advocate of provincialism, Jinnah was looking for ways to restrain the regionalisms of the Muslim-majority provinces so as to bring their combined weight to bear at the all-India level. The cabinet mission plan of May 1946 came close to giving Jinnah what he needed by proposing the grouping of Muslim and Hindu provinces at the second tier while restricting the confederal centre to only three subjects – defence, foreign affairs and communications. Significantly, on 16 June 1946 the All-India Muslim League rejected the mission’s offer of a sovereign Pakistan carved out of the Muslim-majority provinces in the north-west and the Muslim-majority districts of partitioned Punjab and Bengal and accepted the alternative plan for a three-tier confederal constitutional arrangement covering the whole of India.” (p.15)

This idea is central to Jalal’s argument. By highlighting the Lahore Resolution’s reference to “Independent… states” (plural) and their “autonomous and sovereign” nature, she reveals its strategic ambiguity. Jinnah was not a ‘separatist’ from the outset but a ‘confederalist’ seeking maximum provincial power. The crucial evidence she presents is the League’s acceptance of the 1946 Cabinet Mission Plan, which offered a three-tiered confederal India with a weak center, and its simultaneous rejection of a truncated, “moth-eaten” sovereign Pakistan. This demonstrates that Jinnah’s primary objective was to secure power for Muslims within a united India, using the “Pakistan” demand as leverage. The failure of this confederalist vision, she implies, was a refusal of the Congress leadership to accommodate these demands, a point that reverses the direction of the traditional narrative of blame.

If the League did not truly want Partition in the form it took, why did the Indian National Congress, ostensibly the ‘champion of a united India’, ‘agree’ to it? Jalal offers a provocative answer: for the Congress high command, ‘Partition’ was not a failure but a strategic victory. It allowed them to rid themselves of the League’s constant demands for decentralisation, and proceed with their own vision of a strong, centralised state, unencumbered by dissenting provinces or the complexities of power-sharing.

“Partitioning India and seizing control of the colonial state’s unitary central apparatus in New Delhi was the Congress high command’s response to the twin imperatives of keeping its own followers in line and integrating the princely states into the Indian union. From the Congress’s angle of vision, the League’s demand for a Pakistan based on the Muslim-majority provinces represented a mere fraction of a larger problem: the potential for a balkanisation of post-colonial India. It was convenient that in 1947 the communal question had shoved the potentially more explosive issue of provincial autonomy into the background. Cutting the Gordian knot and conceding the principle of Pakistan had a sobering effect on provincial autonomists in the Hindu-majority provinces and generated the psychological pressure needed to temper princely ambitions. Congress’s ability to turn partition into an advantage in state formation is highlighted by the successful integration of the princely states and the rapidity with which the process of constitution-making was completed.” (p.31-32)

This is a stunningly counter-intuitive claim that lies at the heart of Jalal’s thesis on Indian state formation. She portrays Partition not as a tragedy for Congress but as a calculated political masterstroke. The “Gordian knot” was not just the communal problem but the entire question of provincial autonomy and the integration of 562 princely states. By conceding a truncated Pakistan, Congress achieved its primary goal: a powerful, unitary central government. Partition, therefore, became a tool for consolidation, enabling the swift integration of princely states and the creation of a constitution that enshrined central dominance. This argument directly supports her broader claim that the Indian state, from its very inception, contained strong authoritarian and centralising tendencies, which were merely masked by a democratic framework.

The immediate aftermath of this politically engineered division created vastly different starting conditions for the two new states, which would have profound consequences for their political development. India, despite its losses, inherited the lion’s share of the colonial state’s machinery. Pakistan was forced to build its state from the ground up, under immense pressure.

“With partition India lost some of its key agricultural tracts and the sources of raw materials for its industries, especially jute and cotton, not to mention a captive market for manufactured products. The division of the assets deprived India of civil and military personnel, as well as of financial resources, complicating the task of resettlement of the millions fleeing East and West Pakistan, to say nothing of the integration of the 562 princely states. Yet India inherited the colonial state’s central government apparatus and an industrial infrastructure which, for all its weaknesses, was better developed than in the areas constituting Pakistan. It is true that unlike its counterpart the All India Muslim League, which had practically no organisational presence in the Muslim-majority provinces, the Indian National Congress had made an impact on the local structures of politics in the Hindu-majority provinces. However, it is an open question whether, in the process of transforming itself from a loosely knit national movement into a political party, the Congress in fact retained its pre-independence advantages over the Muslim League in Pakistan.” (p.5)

Here, Jalal provides the material and institutional basis for the divergent paths of India and Pakistan. The key phrase is that India “inherited the colonial state’s central government apparatus.” This inheritance provided a crucial degree of institutional continuity and stability, allowing the new Indian government to manage immense crises. Pakistan, by contrast, received a disproportionately small share of the administrative and military assets and had to construct a central authority almost from scratch. This structural weakness, she argues, made Pakistan far more vulnerable to extra-constitutional forces, particularly the military-bureaucratic oligarchy, which stepped in to fill the institutional vacuum left by a weak political class. The final sentence is a subtle but important provocation, suggesting that while Congress started with institutional advantages, its transformation into a ruling party eroded its hitherto moral and organisational authority.

The Ambivalence of Indian Democracy: Beyond the Facade

A major thrust of Jalal’s work is to dismantle the notion of Indian “democratic exceptionalism.” While she does not deny the reality of India’s regular elections and formal democratic institutions, she argues that these coexist with powerful authoritarian undercurrents. She points to the centralising tendencies embedded in the constitution, the use of emergency powers, and the state’s frequent resort to coercive measures to quell dissent. For Jalal, Indian democracy has often been procedural rather than substantive, prioritising the preservation of the central state’s authority over the genuine devolution of power or the protection of minority rights.

Jalal’s critique resonates with a powerful stream of scholarship from within India that challenged the state’s democratic credentials. She finds an intellectual precursor in the work of the eminent political scientist Rajni Kothari, who diagnosed a growing pathology in the Indian polity where the state apparatus itself became an obstacle to democratic deepening. As Jalal points out, Rajni Kothari’s work, State Against Democracy: in Search of Humane Governance, New Delhi, 1988, questions some of the long held axioms of India’s parliamentary democracy (p.264). This context is vital, as it frames Jalal’s analysis not as an isolated outlier but as part of a broader, critical conversation about how the post-colonial Indian state, for all its democratic symbolism, often acted in ways that were profoundly undemocratic.

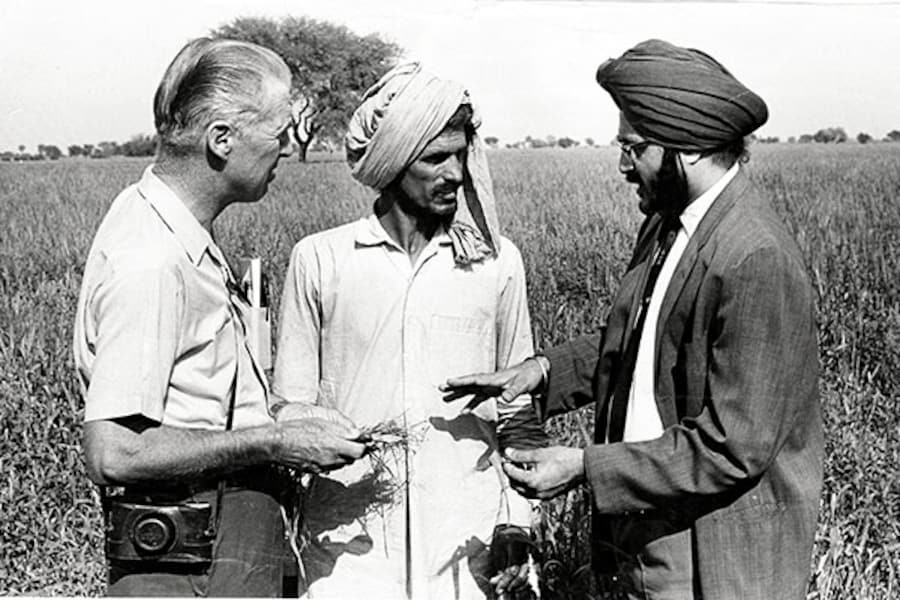

Jalal provides compelling evidence for this argument by examining the state’s developmental strategies, which, despite populist rhetoric, often reinforced central control and exacerbated socio-economic inequalities. She details how the promise of redistributive justice was subverted by a state that prioritised technological solutions and the interests of entrenched elites. For instance, the much-vaunted Green Revolution of the late 1960s was, in her analysis, a political and economic choice that had deep consequences for the nature of Indian democracy.

“The political sea-changes following the emergence of Indira Gandhi as the populist stabiliser were only partly reflected in the objectives of the fourth five-year plan for the period between 1969 and 1973. In a major departure from the Nehruvian years, planners no longer placed much hope in augmenting agricultural production through a fresh round of land reforms. Though land scarcity had no doubt become an important constraint, there was much to be said in favour of reforming the inequities in India’s rural product, credit and labour markets. Yet any such suggestion would have placed the planning commission and the political centre at loggerheads with middling to richer farmers, considerable segments of which continued to provide the Congress’s main support base while others had parted company and contributed in no uncertain way to the 1967 electoral shock. The discrepancies between political alignments and economic interests had been considerably sharpened by the time the fourth five-year plan was on the anvil. So far from matching Mrs Gandhi’s anti-poverty rhetoric and initiating redistributive programmes for the rural and urban downtrodden, the plan plumped for a technological package aimed at inducing the middling to upper landed strata to enhance their production of agricultural commodities. It is widely known that the US president Lyndon B. Johnson pushed Indian planners in this direction by his refusal to deliver shipments of grain to India in 1968 unless the government adopted new policies bolstering the interests of middling to rich farmers. Increased use of fertilisers and high-yielding varieties of seeds were supposed to usher in a ‘green revolution’. Handsome benefits accrued to America’s agro-based industries upon gaining entry into India’s huge market. But since land reforms in the early 1950s had barely grazed the agrarian power structure, the new technological innovations in Indian agriculture at best produced regionally disparate results. Parts of north-western India with better irrigation facilities, Punjab and Haryana in particular, saw a rapid growth in agricultural output but paid the price of increasing political polarisation in the countryside and greater rural-urban migration. There were large parts of rural India which were simply not visited by the ‘green revolution’ of the late 1960s.” (p.135-136)

This passage is a powerful indictment of the Indian state’s development model. It reveals a state prioritising technological fixes and accommodating powerful landed interests — even under pressure from foreign powers like the United States — over substantive social justice initiatives like land reform. The outcome, as Jalal describes, was not uniform progress but ‘regionally disparate results’ and ‘increasing political polarisation.’ This directly supports her thesis that the Indian state, despite its democratic trappings, operated in a highly centralised manner that created new fault lines of conflict. This top-down centralism was further reflected in the very mechanisms designed for grassroots development, which were hollowed out by bureaucratic control, rendering local democratic participation a mere formality.

“There was much ado about creating a village-level leadership, free of manipulation by political parties and exclusively engaged in extending the development effort through the education and organization of the lower levels of the rural strata. Yet for all practical purposes, the development effort at the local levels was squarely in the hands of block development officers and a team of badly trained and underpaid workers who took their orders from mainly conservative IAS officers and state ministers. The top-heavy character of the national planning organisation and the flimsy vehicles of implementation at the local levels of society flew in the face of the inherently disparate and decentralised tendencies informing India’s expanding political arenas at the level of the different regional economies.” (P.128)

Here, Jalal exposes the gap between the rhetoric of ‘village-level leadership’ and the reality of a development process dominated by a conservative, unaccountable bureaucracy. The ‘flimsy vehicles of implementation’ ensured that power remained with central and state-level officials, not with the people. This illustrates a core component of her argument: Indian ‘democracy’ was often procedural, focused on maintaining the authority of the ‘top-heavy’ state, rather than substantive, in which power is genuinely devolved. These examples of economic and administrative centralism provide a crucial backdrop for understanding the state’s handling of political and religious dissent.

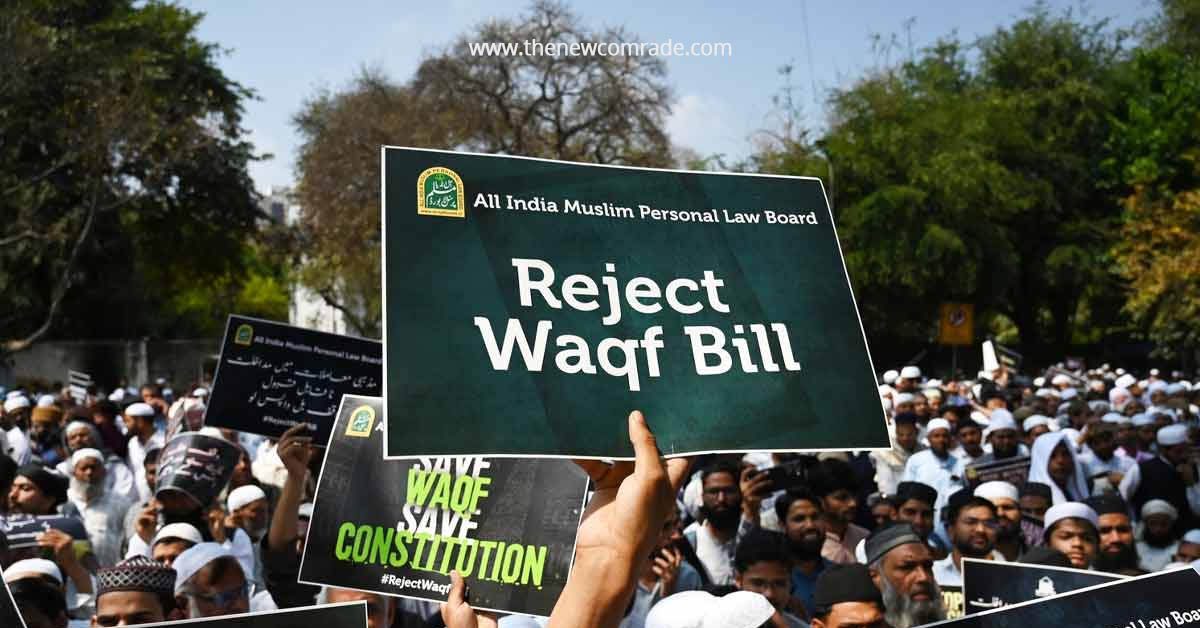

Her analysis of the rise of Hindu nationalism in the 1980s and early 1990s serves as a powerful case study for this argument. The campaign to build a temple at the site of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya revealed the fragility of India’s secular commitments and the state’s willingness to compromise with majoritarian religious fervour, blurring the supposed ideological line separating India from Pakistan.

“The sheer intensity of the Hindu movement to build a temple on the site of a mosque in Ayodhya made the Muslim campaign against the Shah Bano case look placid by comparison. Some extremist Hindu groups, notably the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, had for long been demanding that the Babri masjid be pulled down and a temple to Rama built in its place. The demand is based on the claim that Rama, the mythical hero of the great Hindu epic Ramayana, was born exactly on the spot where the mosque stands. Leading Indian historians have pointed out that the town of Ayodhya itself shifted from one place to another along with the political centre of gravity in the region. Moreover, there is no contemporary sixteenth-century evidence to substantiate the charge that Babur razed Ram’s temple to build the mosque. One of the first historians to write about such a demolition was a Mrs A. S. Beveridge in the late nineteenth century. It is not a coincidence that a historian’s discovery of the fact of a ‘temple-mosque’ controversy occurred about the time that the British were engaged in redefining the social and political meaning of broad religious categories in India. Anyhow those who emphasise faith over history have had no difficulty in accepting an artefact of British colonialism to make a point about a prior Muslim colonialism. On the eve of the 1989 elections the BJP took part in the transportation of ‘holy bricks’ to Ayodhya and a foundation laying ceremony for a temple to Ram near the mosque. The Congress government, afraid of losing some Hindu votes, did not stop the ceremony from taking place. Less than a year after the elections V. P. Singh’s decision to announce a policy of job reservations for backward castes seemed designed to divide the Hindu community by caste and thereby undermine the BJP’s electoral project of mobilising support by playing the communal card. Its leader, L. K. Advani, responded by undertaking a ratha yatra (a chariot journey) which critics quickly dubbed a riot yatra. After traversing large parts of northern India, Advani threatened to arrive in Ayodhya and start building the temple. The BJP had not only taken on its political rivals but challenged one of the main foundations of the Indian state. Those who were in charge of the state apparatus prevented the enactment of the BJP’s plan. Although a government in New Delhi proved to be a casualty of this episode the Indian state managed to scotch an attempted political coup by the extreme religious right. It did, however, appear to give an ideological cover to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s successful manipulation of caste and class-based interests in the state and parliamentary elections of 1991.” (p.244)

This detailed account of the Ayodhya dispute serves as Jalal’s key evidence for the deep-seated biases within Indian “secular democracy”. She first deconstructs the historical claims of the Hindu right, pointing out their dubious origins in colonial-era historiography — a clever way of linking contemporary conflict back to her theme of the colonial legacy. More importantly, she analyses the political dynamics: the BJP’s aggressive mobilisation, the Congress party’s cynical appeasement for fear of losing the “Hindu vote,” and the subsequent political chess match with V.P. Singh’s Mandal Commission policy. While she notes that the Indian state ultimately “scotched an attempted political coup,” her analysis reveals a system deeply rife with majoritarian pressure and political expediency. The episode demonstrates that the formal “secularism” of the Indian state could be easily compromised, and that religious identity politics — the very force supposedly defining Pakistan — was a potent and mainstream force in India as well, thus challenging the clean ideological binary between the two countries.

Appraisal, Limitations, and Enduring Legacy

The strengths of Democracy and Authoritarianism in South Asia are numerous. Its originality and willingness to provoke debate by challenging conventional wisdom are widely acclaimed. The analytical depth and sophistication with which Jalal dissects complex issues, moving beyond surface appearances, are consistently praised. Her interdisciplinary approach, weaving together political, social, and economic threads, and her critical engagement with the notion of Indian democratic exceptionalism, are also highlighted. Her call to redefine core political concepts like democracy, citizenship, and the nation-state within the specific South Asian context is considered a significant intellectual contribution.

However, the scholarly reception also points to several limitations and areas of contention. Her strong focus on structural factors occasionally underplays the agency of political leaders and the impact of elite choices, which can lead to a “victim narrative” for Pakistan where its authoritarian path seems almost predetermined. In its effort to highlight shared authoritarian undercurrents, there are concerns that the book might sometimes overgeneralise or flatten important distinctions between the countries, particularly in its assessment of Indian democracy, where civil liberties and institutional resilience have, historically, been demonstrably stronger than in its neighbours. Methodological questions have been raised regarding a potential selectivity in evidence to buttress her provocative claims about India. Naturally, given its 1995 publication, the analysis predates significant regional developments, such as the full-blown rise of Hindu nationalism to federal power in India, subsequent phases of democratic experimentation and regression in Pakistan and Bangladesh, and the nuclearisation of the subcontinent.

Despite these critiques and the passage of time, Jalal’s work retains remarkable relevance and continues to be an indispensable text for scholars and students of South Asian history, political science, and postcolonial studies. Its enduring legacy lies in its sophisticated analytical framework, which has profoundly shaped subsequent scholarship by encouraging a more critical and nuanced understanding of the region. Her emphasis on decentralisation, state capacity, and the interplay of historical legacies with contemporary challenges remains highly pertinent for understanding current political dynamics, including issues of federalism, civil-military relations, identity politics, and democratic backsliding across South Asia. The book serves as a powerful reminder of the need to contextualise democratic governance and offers valuable insights for policymakers and citizens alike.

Ayesha Jalal’s Democracy and Authoritarianism in South Asia is, thus, a masterful and essential work that fundamentally reframes the discourse on political development in the subcontinent. It compels readers to engage critically with the complex, often fraught, relationship between democratic aspirations and authoritarian impulses that continue to shape the region. While not without its points of debate, its historical depth, comparative insight, and challenging arguments ensure its place as a crucial reference point for anyone seeking to understand the intricate political fabric of South Asia.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.