The following is an interview with Aakar Patel, conducted by Sidheek C S

About yourself…

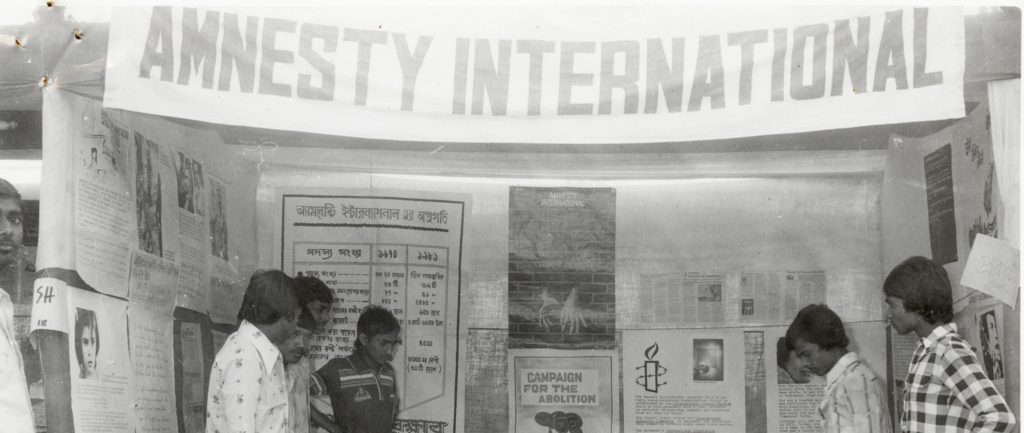

I am a Gujarati; 55 years old. I grew up in a business family. I was in Surat till the age of 25. I studied textile technology at the MS University, Baroda. At the age of 25 in 1995, I moved to Bombay and I got to work as a journalist. Then I was the editor of some newspapers including Midday at Hyderabad with the Deccan Chronicle, the Asian Age in Bombay. My last job as a journalist was as the editor of a Gujarati newspaper in Ahmedabad called Divya Bhaskar. I have been writing columns since, some books, and I work for Amnesty International India as its chair.

Into Amnesty International…

‘Amnesty’, globally, has many journalists in its ranks. The two kinds of people that ‘Amnesty’ tends to hire to run its programs units are journalists and lawyers. So I did not have too much of a problem in terms of making the transition. The standard at ‘Amnesty’ is much higher than the standard would be in a newsroom or in a newspaper or a magazine. But that is just a function of a step change. Generally speaking, I think that the move was, to my mind, very educational for me. I did not know too much about the civil society space till I joined Amnesty International. I think that the attraction towards it has remained strong, which is why I have been with ‘Amnesty’ and with civil society for a little more than 10 years now.

About Amnesty International..

I think that ‘Amnesty’ should be understood as the United Nations is understood. There is a secretariat, which is in London. But each country which has an ‘Amnesty’ section or a national office is independent in the work that it pursues. The rule during the Cold War was that people could not work on their own country. So the rule assumed that somebody working on Russia would need to be non-Russian to specialize and to work on it because of the perceived bias. That rule no longer exists. I would say that there is no external influence on the work that ‘Amnesty’ does anywhere in the world, including in India. The work that we choose to do reflects the concerns within the constitution of India and the guaranteeing of fundamental rights. The Indian state very casually uses national security and security apparatus to muzzle NGOs. Not just to muzzle NGOs, it also goes after the media, it goes after opposition leaders and uses whatever tools it has at its command. Some of these include national security, but they also include things like money laundering, CBI and the misuse of the ED. This is not proper for a democracy and I think any functional democracy needs to have a healthy environment in which civil society organizations and NGOs can thrive without fear of the government muzzling them or of the government attacking them in any way, which is quite common in India.

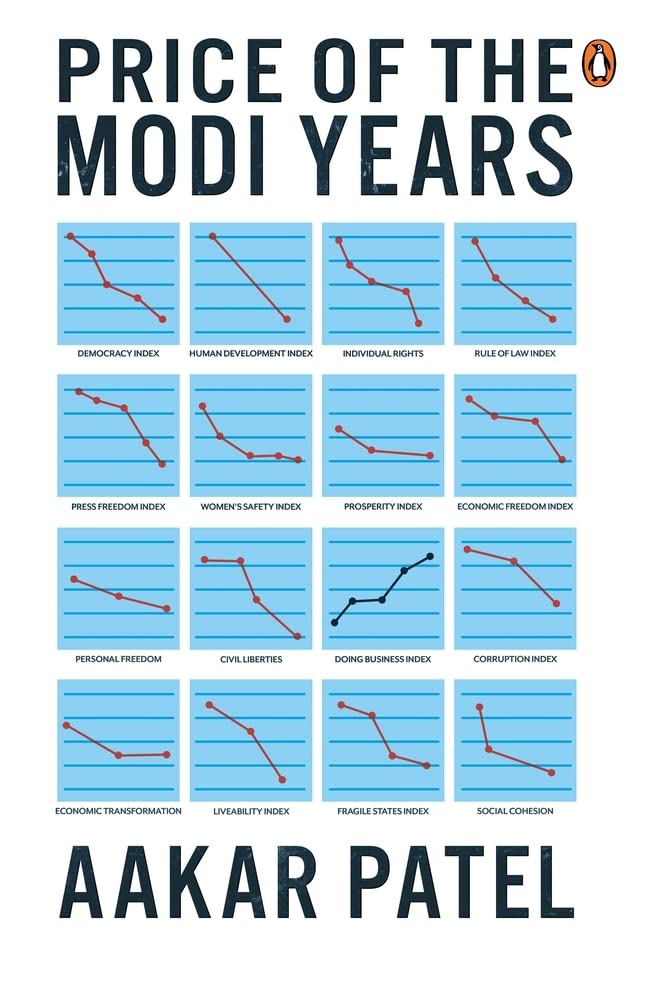

Your books..

I think that writers are motivated to write. What you write has to be of interest, not only to the reader but also to yourself. It is difficult to write a book, if one is uninterested in that subject. So to me, the authoritarian nature of the government in India, particularly after 2014, has been a subject of deep concern and deep interest. It is what this concern is what has motivated me to keep writing on the same subject for several years. So far as the government goes, I think the government, generally, does not have interest in books. In India, Kerala is the only state where a best-seller book sells 35~40,000 copies. In English, which is what I write in, a best-seller generally sells only 3000 ~ 4000 copies because people do not read or buy books. I would say that Malayalis are different. But, because of the fact that people do not read and buy books elsewhere, the government is not very bothered about what the books say. You could say a great deal of things which are antagonistic to the government in a book and it would not care. But if you were to say the same thing in condensed form in a tweet or on Facebook, the government would come after you if it became popular. That, I think, is the difference that for people who write books such as me, the problems from the government are far fewer than those activists who use mostly social media to communicate their work.

After the closure of Amnesty International – India Chapter..

We had a series of problems with the government. The earliest one that I can remember was a sedition case in 2016. The complainant was the ABVP. But it did not show up in court even once. The court closed the case after two years. Similarly, we expect that all the cases that have been filed against us, whether by the CBI or the ED, will, in time, be decided in our favor. One of the problems is that the justice system in India takes too long. But the hope is that, in time, we will come out fully acquitted. We have done nothing wrong. All the accusations that have been made against us are, frankly, malicious and meant to make us stop doing our work rather than anything else. I believe that we should be back in due course, hopefully this year or the next.

About the travel ban you have been subjected to…

There was my name was on the exit control list, but now it is not on the list any more. Of course, I do have to take the permission of three courts each time I travel. After that first time and the second time I was stopped, I have travelled abroad. I went to the United States twice last year to speak at Universities, and I went to Europe twice last year. I went to Turkey before that. So there is no ban as such.

The idea that anybody who has been accused of a crime should be put on this list, without their being told, is problematic. If you tell the person they are on the list and they cannot fly, they can move court and they can fight the order through the justice system. If you do not tell them and it is kept a secret, they spend all the money, they go to the airport and then they are told at the desk that they cannot fly. That is wrong and this is one thing that the government should change for all people, not just for me.

About help from overseas….

All human rights groups, international or local, tend to have, and operate, in a system of solidarity. So there is no real difference either in the way that they operate and there are no secrets because they are not competing. This is not like the corporate world where one company competes against another company to sell up, to sell its products or its services. All of us want the same thing. We want human rights to be upheld. We want human rights defenders not to be persecuted. To that extent, we extend to one another solidarity. That is how we help each other. Have they been sacrificial lambs? I would say no. There is no real coordination between international human rights groups and any government, whether in the, what we call, Global South or in Europe or the US. There is no real contact or a connection between what governments seek and what human rights bodies seek. What we want is that in each domain that we operate and in some that we do not, that the governments there follow international human rights law. In those countries that have a good sound constitution like I think ours does, we want the government to follow the constitution as closely as it can. There is no question that these bodies, these groups, would be seen as doing another government’s work because that is not the other government’s interest nor is it ours.

Evaluating the work done by Amnesty International – India…

Our history is quite old. It could be divided to several periods, going back to about more than 50 years ago when George Fernandes was a member – he was one of the earliest members of Amnesty International in India. The work we should see is of two kinds – one is research, where human rights violations – mostly by the state – are documented. The second part is trying to resolve the problem that the research shows, either by engaging with the government, advocacy as it is called, or through campaigning, through mustering of enough public opinion that the government recognizes that there is a problem, whether in law or in policy and moves to change it. On the first count, on the research, we have done reasonably well. I think that a lot of our work, including on things like Kashmir, where the Public Safety Act and AFSPA have been the subjects of our research. The Government of India itself has accepted a lot of the findings of these reports. Similarly, our work on under-trials, on the freedom of expression, on the rights of the Adivasis in the coal-mining areas. A lot of the research and the value of it is accepted, if not officially by the government, in such things as statements that it makes to Parliament, as we saw on the 1st of January 2018 when the Rajya Sabha was told that not a single case that the J &K police had filed against armed forces had resulted in a chargesheet and prosecution in a civilian court. This is basically the research that we had put up. So on that count, it is fine. On the count of campaigning on being able to effect change with the state, in the state, I would say that there is some scope for improvement there. One reason for that is that the government in India, like many of the governments in our part of the world, does not see engaging with human rights groups as being useful. The government sees us in adversarial terms, if not being openly hostile to us. This is wrong. That is not the way that democracies function and we hope that it changes and I think it will change in time.

Political liberties…

Partly, the situation of opposition work being pushed to exile, already exists. Many people who oppose or dissent with what the government says or does are in jail. Many who are not in jail do not speak up for fear of being in jail. Opposition politicians, including in places like Maharashtra and West Bengal, are sent to jail primarily because of the fact that they are the most outspoken against the policies of the government. Nawab Malik in Maharashtra would be an example. This is true also of those people in civil society who are jailed because of what they say. Omar Khalid, I think would be one. Siddique Kappan was somebody who should not have been jailed, should not have spent all those many months in jail, but was jailed, I think purely because of the fact that A, This government is very hostile to Muslims. And B, the idea that dissent should be punished and it should be punished without the justice system, is held fairly common with this government, which is one reason why the opposition is less outspoken than it would otherwise be. Maybe if not the threat of exile, the threat of a punishment in jail would definitely weigh on the mind of the opposition leaders when they speak against the government.

About the way forward in India for civil society…

They will continue doing the work that they do. India has a very vibrant civil society and a very diverse one. So if we look at many issues, we have actually won on some of the more serious things that we have fought for, including things like right to food, right to education, right to information and right to work under MNREGA. There are other bits where we have not done as well. Our work on human rights violations in places like Kashmir or now in Manipur, fighting against the laws that this government, in particular, has brought after 2014. We have been less successful in being able to push back against that. But I see no reason given the fact that India remains constitutionally a democracy. There is some space for us to work in. That space should be used as effectively in the future by civil society as it has been in the past.

In solidarity with Palestinian cause…

We should not have had Smotrich come to Delhi. He is part of a government full of war criminals. I think the government in India made a mistake in embracing Netanyahu, in the first instance, but particularly after the 7th of October and the genocide against the Palestinian people. India had, formally, held a sympathetic position on the issue of Palestine, for a long time. It is quite petty, childish and non-productive for the government of India to embrace the Zionist entity purely because of a dislike and a despise of its own Muslim citizens. It is quite dangerous, as well. It makes for very poor foreign policy. What India should be doing is to muster international opinion to make sure that the US stops arming Zionists, that there is sufficient pressure on the Zionist government to stop bombing civilians to make sure that the United Nations resolutions on the two-state solution are followed. India should be much more active than what it has been doing, so far, under the BJP.

Jignesh Mevani phenomenon …

I have not been to Gujarat too many times in the last few years. So, I do not know what the position on the ground is. His constituency is not very close to my house, my home is in Surat. But he is exceptionally talented. The ability Jignesh has to mobilize people and the way in which he did it, using the issues that he did, was extremely effective. It is not easy to defeat the BJP in a constituency there. The fact that he has managed it would indicate that he has something special in him. I can only hope that that special thing is retained, if not shared with more people in the opposition, so that they can learn from his victory. Generally, he is really bright and I wish that he has a larger role in politics in the future.

On Manto and your other literary pursuits…

There are not many writers who were writing a hundred years ago like Manto was, that are still read. There is almost nobody else, I can think of ,who is still relevant. Manto’s prime attraction to me comes out of his relevance, that the Bombay he is describing in the 30s and 40s is not very different from the Bombay that I have seen myself in the 90s.

The reason for that is that, though he is writing all those decades ago, he is able to capture something of that city which only a very very good writer or a writer of the highest caliber can capture, which is why he is not only still read, he is still relevant. To me, the more interesting bits of his writing are his non-fiction pieces, which are the ones that I translated. Many people have translated his fictional works and it is true that he is one of the great writers of short stories. But he is also an exceptional writer of essays as I discovered and as I tried to show to readers of English in my translation of his works.

Any future intentions in Journalism…

I continue to write columns but I have no interest in going back to journalism because I think civil society is too vast for me, at least a much more interesting space and a much more relevant space than journalism is. There are a few disappointing things about journalism not the least of which being that newspapers are in decline. All of my work in journalism had been in newspapers. It is very sad to see that, particularly in English, they have not only lost their readership, but they have also lost their relevance. So, I would prefer to stick with civil society.

(Aakar Patel is a journalist, activist and author. He currently serves as the chair of the Board of Amnesty International in India)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.