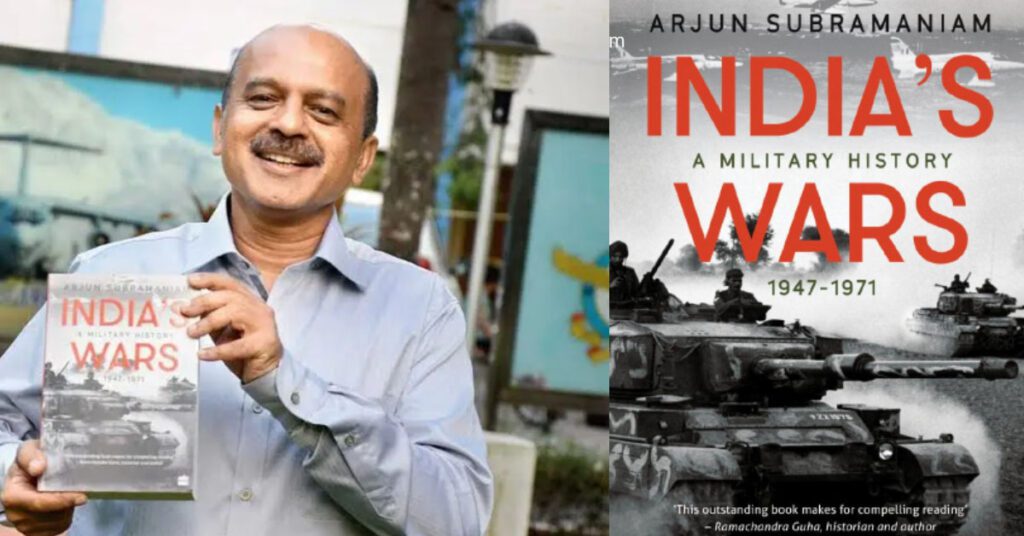

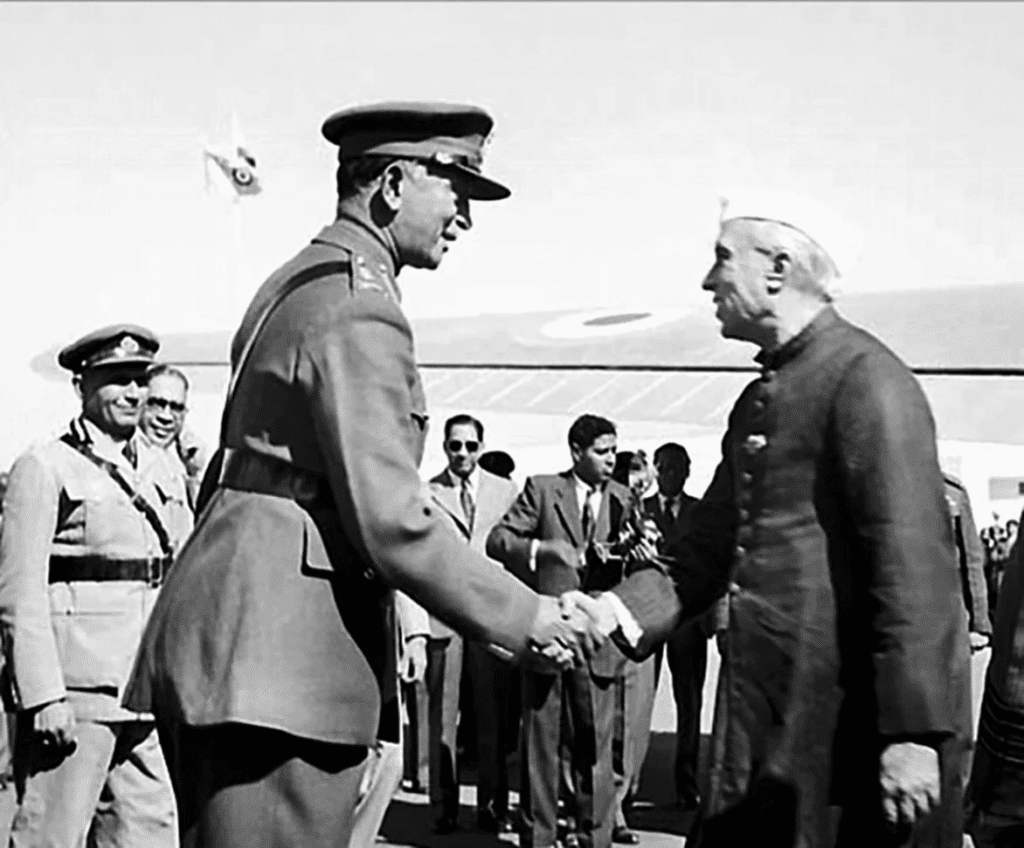

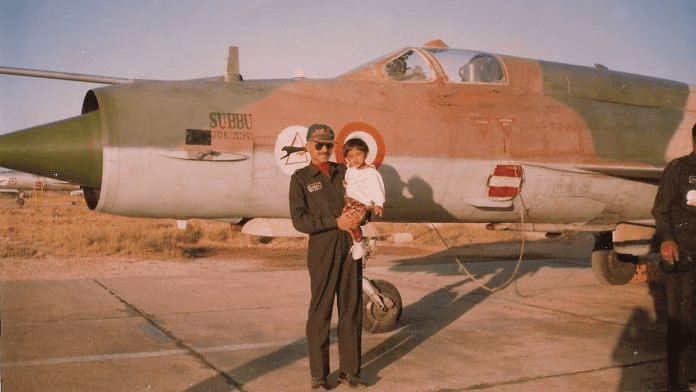

The landscape of modern Indian military history has long been an opaque, sparse and challenging terrain for the curious reader. For decades, it has been dominated by two unappealing extremes: the dense, dry, and often sanitised official histories commissioned by the government, and the chest-thumping, frequently jingoistic popular accounts that prioritise patriotic fervour over critical analysis. A comprehensive, yet readable single-volume narrative of India’s foundational conflicts has remained a conspicuous void. It is this void that Air Vice Marshal Arjun Subramaniam (Retd.), a decorated fighter pilot who transitioned into a military historian, seeks to fill with his work, viz. India’s Wars: A Military History, 1947-1971. This is not a mere chronicle of battles won and lost; it is an exploration of how a nascent nation-state, born amidst the chaos of Partition, forged its identity, secured its borders, and established its power through the crucible of conflict. Subramaniam has produced a text that goes to lengths in its operational detail, its ground-breaking tri-service perspective, and its human portrayal of war, probably establishing a new benchmark for military historiography in India, even as its practitioner’s focus occasionally narrows its analysis of the complex political tapestry against which these wars were fought.

A Historiographical Mission

Before delving into the conflicts themselves, it is essential to understand the intellectual mission that animates this book. Subramaniam is not just a historian; he is an advocate. He begins with a powerful lament for the marginalisation of military history in India’s dominant discourse. He argues that a nation that fails to critically and honestly engage with its military past risks a form of strategic amnesia. He writes with a clear sense of purpose, aiming to craft a narrative that seeks to correct this imbalance. In his preface, he states his ambition plainly: to write a history that is “analytically sober, intellectually engaging …” (p. xxv).

This mission shapes his entire approach. He meticulously synthesises a vast array of sources—official war diaries, regimental histories, memoirs—but his most vital and original contribution comes from his extensive use of oral history. By interviewing veterans from the foxholes, the cockpits, and the bridges of naval vessels, he rescues the human element from the dry data of official reports. He seeks to tell the story of the Indian military as an institution defined by its core values. He identifies this as “a story of a ‘professional’ and ‘secular’ fighting force that has time and again risen to the occasion to safeguard the core values of the Indian state …” (p. xxv). This dual commitment—to analytical sobriety and to celebrating the professional ethos of the armed forces—is the powerful engine that drives the narrative forward.

Kashmir, 1947-48

The story begins in the maelstrom of 1947, with a military cleaved in two by Partition and an officer corps depleted by the departure of the British. The first test came almost immediately in Jammu and Kashmir. Subramaniam’s prose vividly captures the frantic, ad-hoc nature of India’s response to the advance by tribal militias. The narrative of the initial airlift to save Srinagar is gripping. He details the spirit of Lieutenant Colonel Dewan Ranjit Rai, who, upon landing at the besieged airfield, “led his small band of warriors from the front in a desperate bid to halt the raiders’ advance,” ultimately sacrificing his life but buying precious time (p. 61).

Beyond tales of individual heroism, Subramaniam provides a sharp analysis of the war’s strategic conduct. He highlights the leadership shown by commanders on the ground, such as Brigadier Pritam Singh, whose year-long defense of the besieged town of Poonch reflected tactical ingenuity and sheer endurance. He describes how Singh and his men held out against odds, a feat that was a “classic example of a commander leading from the front and inspiring his men to achieve the impossible” (p. 80). Yet, this operational success is contrasted with the political decisions made in New Delhi. Subramaniam is critical of the decision to take the issue to the United Nations and accept a ceasefire when, he believes, Indian forces held the momentum. He quotes the exasperated General K.M. Cariappa, who felt the army was “in a position to clear the whole of J&K of the enemy,” viewing the ceasefire as a politically imposed strategic blunder that would embed the conflict for generations (p. 91). This chapter powerfully establishes a recurring theme: the complex and often fraught relationship between military means and political ends.

National Trauma in 1962

If the first Kashmir War was a crucible, the 1962 Sino-Indian War turned to be a national humiliation. Subramaniam’s account of this conflict is the book’s most searing and analytically incisive section. He unflinchingly dissects the “Himalayan Blunder,” attributing it to a catastrophic cascade of failures at the political, diplomatic, and military levels. He is scathing in his critique of the political leadership, particularly Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and his controversial Defence Minister, V.K. Krishna Menon. He argues their worldview was a dangerous mix of idealism and hubris, leading to the disastrously ill-conceived “Forward Policy” that pushed unprepared troops into untenable positions. He writes, “The politico-bureaucratic combine in Delhi pushed a reluctant military, suffering from neglect and poor leadership, into a disastrous conflict with the Chinese” (p. 165).

The book brings to life the horrific conditions faced by the Indian soldier, sent to fight a modern, well-equipped army in the freezing altitudes of the Himalayas without proper acclimatisation, winter clothing, or even adequate weaponry. Yet, amidst this strategic ruin, Subramaniam finds stories of valour, like the Battle of Rezang La. Here, C Company of 13 Kumaon, led by Major Shaitan Singh, fought to the last man against overwhelming Chinese forces. Subramaniam writes that of the 123 men in the company, 114 were killed (p. 211).

Subramaniam’s most original and forceful argument in this section concerns the political decision not to use the Indian Air Force (IAF) in an offensive role. As a former aviator, he brings an expert’s eye to this matter. He contends that while airpower may not have changed the final outcome on the ground, it could have inflicted significant costs on the Chinese. Failure to use the IAF, he argues, stemmed from a paralysing fear of escalation in New Delhi. “The non-use of combat air power,” he concludes, “was a cardinal blunder and a demonstration of strategic timidity that is difficult to justify even five decades after the event” (p. 222). The 1962 war was traumatic and a wake-up call, shattering India’s illusions and forcing a massive modernisation of its armed forces.

The Learning Curve of 1965

The 1965 Indo-Pakistani War is presented as a crucial, if messy and inconclusive, chapter in the Indian military’s evolution. It was a war born of Pakistani miscalculation, rooted in the belief that India remained a soft state, demoralised by its defeat in 1962. Subramaniam details how Pakistan’s Operation Gibraltar (the infiltration of disguised army corps into certain points in Kashmir) and Operation Grand Slam (an armoured thrust) were rebuffed.

The narrative is filled with accounts of combat, particularly the great tank battles that defined the conflict. The Battle of Asal Uttar stands out. Here, Indian armoured units, employing their Centurion tanks with tactical skill, lured a larger force of technologically superior Pakistani Patton tanks into a trap. Subramaniam describes the battlefield as a “graveyard of Pattons,” a decisive victory that “blunted Pakistan’s main offensive and turned the tide of the war in the western sector” (p. 317). He also highlights the coming-of-age of the IAF, which, though still grappling with coordination issues, engaged the Pakistan Air Force in aerial duels, with pilots like Squadron Leader Alfred Cooke earning the moniker “Sabre-slayer.”

However, Subramaniam offers a sober assessment, characterising the war not as a clear victory but as a stalemate that exposed continuing weaknesses. The most significant of these was the poor level of inter-service cooperation. “Jointmanship,” he notes, “was still a nascent concept, and the army and the air force fought their own wars with little synergy or coordination” (p. 343). The 1965 war was thus a vital learning experience. It demonstrated a newfound resolve and resilience, but it also starkly illuminated the doctrinal and organisational reforms still required to transform the Indian military into an integrated and decisive fighting force.

Bangladesh, 1971

The 1971 war is the grand climax of the book, the moment when all the lessons of the previous decades—in politics, strategy, and joint operations—coalesced into a victory. Subramaniam portrays the war not simply as a military campaign but as the execution of a masterful strategy, a perfect “symphony of war.”

He gives credit to the political leadership of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, praising her strategic patience and clarity. Faced with a political crisis in East Pakistan, she resisted the urge for immediate action. Instead, she used the intervening months to prepare the military meticulously and to conduct a diplomatic campaign that isolated Pakistan and secured a treaty with the Soviet Union, effectively deterring American or Chinese intervention. These political actions created the perfect conditions for military success. When asked by the Prime Minister when the military would be ready, Army Chief Sam Manekshaw famously replied, “I guarantee you a 100 per cent defeat in that case,” insisting he needed months to prepare (p. 396). Gandhi’s willingness to trust her commanders and give them the time they needed was a hallmark of fruitful civil-military relations.

When the war finally began, the Indian military operated with a synergy unseen hitherto. Subramaniam’s tri-service perspective is at its most potent here. He details how:

• The Indian Army, alongside the Bengali Mukti Bahini, executed a “blitzkrieg”-style campaign, bypassing heavily defended Pakistani garrisons and racing for the strategic heart of East Pakistan: Dhaka. The audacity of commanders like Lieutenant General Sagat Singh, who used helicopters to leapfrog his forces across the mighty Meghna River, is highlighted as a key to unhinging the entire Pakistani defence.

• The Indian Air Force achieved complete air supremacy over the eastern skies within 48 hours, a “remarkable feat” that allowed it to systematically destroy Pakistani military infrastructure and provide unfettered support to the advancing army (p. 427).

• As for the Indian Navy, in the west, its missile boats launched night attacks on Karachi harbour, crippling the Pakistani Navy in Operations Trident and Python. In the east, it imposed a “stranglehold blockade” that cut off all hope of reinforcement or escape for the Pakistani forces (p. 445).

It was this “orchestrated and executed tri-service campaign” that led to the surrender of 93,000 Pakistani soldiers in Dhaka after a war of just thirteen days (p. 465). The 1971 victory was the apotheosis of the Indian military’s journey, the moment it came of age as a regionally dominant force.

Blind Spots

‘India’s Wars’ is not without limitations, which stem directly from the author’s background as a military professional. The book’s primary analytical lens is, understandably, military effectiveness, and political decisions are often judged almost exclusively by their impact on the battlefield. The sustained and sharp criticism of Nehru’s leadership, while entirely valid from an operational standpoint, could have been enhanced by a wider exploration of the non-military pressures he faced: the imperatives of domestic routine politics, compulsions of maintaining economic activity, and declared commitment to non-alignment. The book details the military consequences of his policies but is less invested in exploring their complex political origins. This results in a portrayal of the political leadership that sometimes lacks the nuanced context afforded to military figures. The practitioner’s frustration with political dithering occasionally overshadows the historian’s imperative for holistic analysis.

Furthermore, this focus can lead to a slightly one-dimensional portrayal of India’s adversaries. The strategic calculus and internal political dynamics of Pakistan and China are not examined with the same depth as India’s own. The opponent sometimes appears more as a set of military problems to be solved rather than a complex political entity with its own rationale and compulsions. A more developed interactive picture of the conflicts would have strengthened the analysis further.

An Indispensable Chronicle

Arjun Subramaniam has produced a book that is both a serious resource and a gripping read. His command of operational detail and his championing of a tri-service narrative is ground-breaking.

‘India’s Wars: A Military History, 1947-1971’ is an indispensable work for any student of Indian history, strategic studies, or international relations. It attempts to reclaim military history from the margins. By giving voice to the soldiers, sailors, and airmen who fought these wars, and by providing an analysis of India’s military learning curve, Subramaniam does more than just recount history; he illuminates the complex process by which an institution was forged in the heat of combat. It seems to be the most accessible military history of India’s formative years yet written, and it sets an enduring standard for the field, though subtly reflective of the political discourse of the Modi-RSS era in which it is brought out.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.