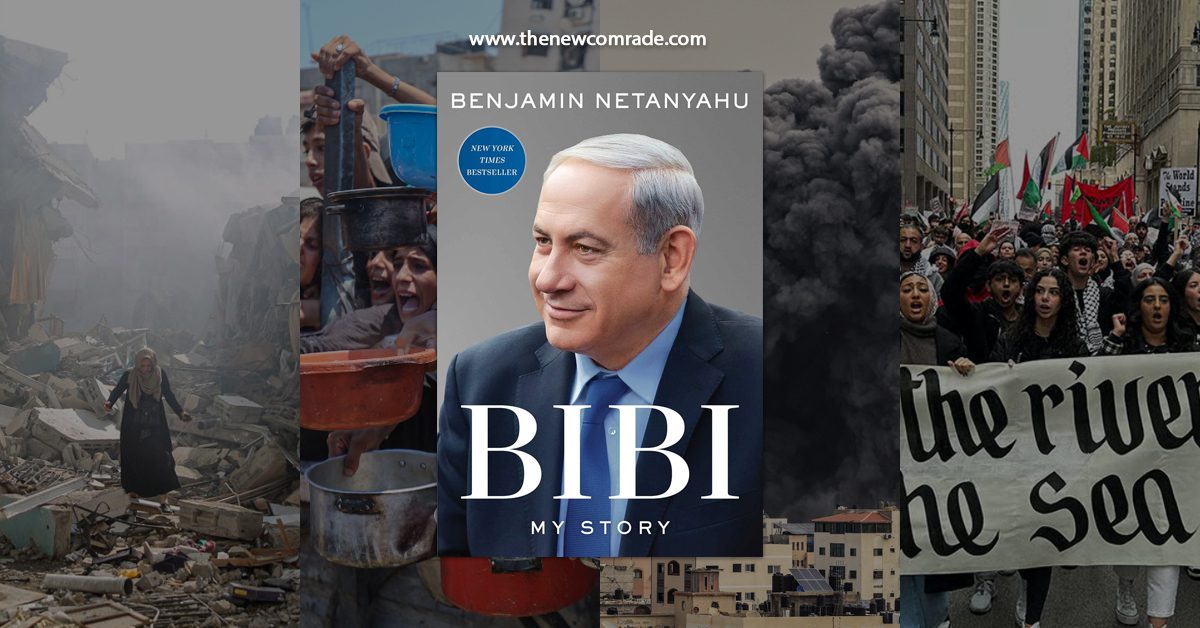

Benjamin Netanyahu’s autobiography, Bibi: My Story, is not merely a memoir of political survival; it is a monumental testament to the victory of the particular over the universal in the 21st century CE. It serves as the definitive textual rebuttal to the ethical lineage of Hannah Arendt, Albert Einstein, Isaac Deutscher, and Edward Said. Where these thinkers posited that the moral survival of the Jewish people—and indeed, humanity—depended on transcending the narrow boundaries of tribe and state to embrace a shared human condition, Netanyahu’s text is a fortress built to keep the universal at bay.

Reading Bibi requires us to resurrect the warning issued by Arendt and Einstein in their famous 1948 letter to the New York Times. They warned against the rise of the Herut party (the ideological forebear of Netanyahu’s Likud), describing it as “closely akin in its organisation, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties.” They feared a Zionism that worshipped the state, fetishised the military, and dehumanised the native population. Bibi: My Story is the documentation of how that feared fringe moved to the centre, becoming the dominant operating system of the Zionist State.

This review posits that Netanyahu’s narrative is a constructed mythology designed to erase the “Non-Jewish Jew” — Isaac Deutscher’s term for the Jewish revolutionary who embraces the world — and replace him with the “State Jew,” for whom the apparatus of power is the only true idol.

History as Trauma and Weapon

The narrative architecture of Bibi rests entirely on the shoulders of one man: Benzion Netanyahu. To understand the son, one must analyse the father through the psychoanalytic lens of Jacqueline Rose and the historiographical critique of Shlomo Sand. Benzion, a historian of the Spanish Inquisition and the secretary to Ze’ev Jabotinsky, instilled in his son a “catastrophic” view of history.

In the memoir, Netanyahu recounts his father’s teachings not as subjective interpretations, but as revealed truth. The lesson is singular: The world is structurally anti-Semitic; the Jew is eternally the victim; and the only guarantee of life is overwhelming force. This aligns with what Salow W. Baron called the “lachrymose conception of Jewish history”—a history of tears. However, unlike the religious tradition which responded to this suffering with prayer or ethical introspection (as Gershom Scholem might analyse in the context of Jewish mysticism), Netanyahu responds with the accumulation of power.

Shlomo Sand, in The Invention of the Jewish People, argues that Zionist nationalism reconstructed Jewish identity into a biological-political race moving through time. Netanyahu’s memoir embraces this essentialism without hesitation. He writes of the Jewish people as a singular, unified organism that has “returned” to its estate. There is no room in his narrative for the ruptures, the conversions, or the diverse diasporic histories that Sand highlights. For Netanyahu, history is a straight line from King David to himself.

Yakov M. Rabkin, in his critique of Zionist engagement with Judaism, would argue that Netanyahu’s reverence for his father’s secular, nationalist history represents a rupture with the Torah. Benzion’s Zionism, as depicted in the book, is atheistic in practice but messianic in structure. The “Messiah” is not a divine figure, but the Zionist entity itself. This displacement of the divine onto the state is what Hannah Arendt warned would lead to the “banality of evil”—not in the sense of the Holocaust, but in the bureaucratic normalisation of violence for the sake of the state.

Netanyahu describes his upbringing in Jerusalem and later in the United States as an education in “reality.” But through the lens of Maxime Rodinson, who viewed the Zionist entity through the framework of settler-colonialism, we see that Netanyahu was being educated in the logic of the settler. The indigenous population of Palestine — the “Arabs”—are largely absent from his childhood memories, appearing only as faceless threats or distant shadows. This constitutes the first act of what Edward Said called “The Permission to Narrate”: the erasure of the Other’s presence to clear the stage for the nationalist drama.

American Years

A significant portion of the early memoir is dedicated to Netanyahu’s time in the United States, specifically Philadelphia and MIT. Here, the critique of Ernest Mandel (on late capitalism) and Noam Chomsky (on American imperialism) becomes vital.

Netanyahu portrays himself as an outsider in America, a proud Zionist in a land of assimilation. He speaks with disdain for the ‘liberal’ Jew — the tradition of Einstein, Freud, and indeed Chomsky — viewing it as “naive” and “weak.” Isaac Deutscher celebrated the “Non-Jewish Jew” who lived on the margins of civilisation and thus had the clarity to critique power (Spinoza, Marx, Trotsky, Rosa Luxemburg). Netanyahu, in his Philadelphia years, consciously rejects this legacy. He is not interested in critiquing power; he is interested in acquiring it.

He describes his education at MIT and his time at the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) as the formation of his economic worldview. Here, we see the roots of his neoliberal ideology. Through Ernest Mandel’s Marxist framework, Netanyahu represents the fusion of the “Security State” with “Global Capital.” He adopts the language of the free market — efficiency, privatisation, deregulation — and applies it to the Zionist project. He views the state not as a collective responsible for the welfare of its citizens (the old Labour Zionist ideal, however flawed), but as a corporation that must be “lean” to compete.

Noam Chomsky has long argued that the ‘US-Israel’ relationship is sustained not just by a lobby, but by the strategic utility of Zionist entity to US hegemony. Netanyahu’s memoir inadvertently confirms this. He describes his early efforts in Hasbara (advocacy) as an effort to align the Zionist entity with American power interests. He learns to speak the language of the American Right — the language of “Western Civilisation” fighting “Barbarism.”

For Einstein, the security of a Jewish home depended on “satisfactory relations with the Arab people.” For the young Netanyahu, shaped by America’s Cold War mentality, security depended on total dominance and alignment with the Western imperial superpower. He adopts an Orientalist worldview where the East is chaotic and violent, and the West (Zionist entity and the US) is rational and moral.

Trauma of Entebbe: Politicisation of Grief

The emotional fulcrum of ‘Bibi: My Story’ is the death of his elder brother, Yonatan Netanyahu, during the raid on Entebbe in 1976. This event is the “primal scene” of Netanyahu’s political identity.

Here, we must engage the First Key New Exposure of the text: The deliberate construction of a “Cult of the Fallen” to justify political immunity and the rejection of compromise.

The memoir reveals how Benjamin Netanyahu — and his father Benzion — transformed Yonatan from a soldier into a secular saint of Revisionist Zionism. Moshe Zuckermann, in ‘Shoah in the Promised Land’, analyses how Zionist society sacralises the military to silence dissent. Netanyahu takes this further. In the book, Yonatan is depicted as the perfect Zionist: a warrior-philosopher who understood that “the only way to deal with terrorists is to kill them.”

By canonising Yonatan, Netanyahu creates a shield against the universalist critique. How could Judith Butler speak of the “grievability” of Palestinian lives when Netanyahu presents his own grief as absolute and exclusive!

The memoir exposes a psychological dynamic: Netanyahu believes he is living Yonatan’s unlived life. This leads to a messianic sense of destiny. Jacqueline Rose, in The Question of Zion, argues that Zionism is driven by a form of “collective insanity” born of trauma. Netanyahu’s narrative confirms this. He is not a politician making rational calculations; he is a brother on a permanent revenge mission against the forces of “Terror.”

This section of the book also reveals Netanyahu’s total refusal to acknowledge the Palestinian perspective on Entebbe or the hijackings of the 1970s. While the hijackings were desperate acts by a displaced people seeking visibility, to Netanyahu they are simply manifestations of “evil.” He strips the Palestinian resistance of all political context, reducing it to a mere pathology. This allows him to categorise all future Palestinian resistance — whether violent or non-violent (like BDS) — as a continuation of the same ‘irrational hate’ that killed Yonatan.

Pro-Zionist Leadership

In Bibi: My Story, Benjamin Netanyahu constructs a distinctive geopolitical map of the contemporary world, dividing leaders less by conventional ideology than by their alignment with the Zionist entity’s security doctrine and Zionist claims. Support for the Zionist entity, in Netanyahu’s narrative, is measured not primarily by rhetorical sympathy but by concrete policy decisions — especially those that reject Palestinian veto power over regional diplomacy, endorse Zionist territorial claims, and prioritise strength over concession. Through this lens, Netanyahu identifies a cohort of leaders he views as pro-Zionist or functionally anti-Palestinian, while casting others as ideological rivals whose policies, in his view, undermine Zionist entity’s survival.

Among all world leaders, Donald Trump occupies the most exalted position in Netanyahu’s memoir. Trump is portrayed as the most pro-Zionist president in U.S. history, a “trailblazer” who dismantled decades of diplomatic orthodoxy. Netanyahu credits Trump with recognising Jerusalem as the Zionist entity’s capital, acknowledging Zionist entity’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights, affirming the legality of Jewish settlements, withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal, and brokering the Abraham Accords. These moves are framed as revolutionary because they advanced peace without territorial withdrawal or Palestinian consent. Netanyahu repeatedly contrasts Trump’s approach with the traditional peace paradigm, presenting it as vindication of his long-held belief in “peace through strength” rather than land-for-peace. Trump’s unpredictability, while challenging, is depicted as an asset that unsettled Zionist entity’s adversaries and emboldened regional allies.

By contrast, Barack Obama is depicted as Netanyahu’s principal ideological antagonist among U.S. presidents. While not characterised as hostile to the Zionist entity’s existence, Obama is portrayed as captive to what Netanyahu calls a “distorted Palestinian narrative.” The memoir emphasises Obama’s insistence on settlement freezes, pressure for concessions, and pursuit of the Iran nuclear deal as policies fundamentally at odds with Zionist entity’s security needs. Netanyahu contrasts Obama’s reliance on soft power, culture, and diplomacy with his own emphasis on military strength, arguing that moral standing alone cannot protect a nation from destruction. Obama thus emerges as a well-intentioned but dangerously misguided leader whose worldview conflicted with Zionist realism.

Joseph Biden receives a more nuanced treatment. Netanyahu underscores their long personal acquaintance and Biden’s instinctive support for ‘Israel’s right to self-defence’, particularly at the outset of military confrontations. However, Biden is also shown as constrained by humanitarian concerns, domestic political pressures, and calls for ceasefires. In Netanyahu’s framing, Biden is friendlier than Obama but lacks Trump’s decisiveness. Supportive yet cautious, Biden embodies a transitional figure — personally sympathetic but institutionally bound to older diplomatic frameworks.

William Clinton is recalled primarily as a political adversary during Netanyahu’s first premiership. Netanyahu recounts Clinton’s active opposition to his 1996 electoral victory and portrays his administration as emblematic of a U.S. leadership style that prioritised international consensus and Palestinian negotiations over Zionist entity’s strategic imperatives. Clinton thus represents an earlier phase of American diplomacy that Netanyahu consistently resisted.

John Kerry functions in the memoir as a symbol of Washington’s traditional peace-process orthodoxy. Netanyahu invokes Kerry’s assumption that ‘Israeli-Palestinian peace’ must precede broader regional normalisation in order to reject it. The Abraham Accords are presented as an empirical refutation of Kerry’s logic, reinforcing Netanyahu’s claim that the Palestinian issue need not dictate Middle Eastern diplomacy.

Beyond contemporary U.S. presidents, Netanyahu reserves deep admiration for Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, whom he presents as ideological soulmates. Reagan is credited with restoring American strength and moral clarity, creating conditions for a robust U.S.–Israel alliance. Thatcher is portrayed as a principled defender of democracy and a personal admirer of Zionist ‘resilience’, famously praising Zionists as “fighters.” These leaders exemplify, in Netanyahu’s telling, a moral-strategic worldview aligned with Zionist self-assertion.

In Europe, Netanyahu singles out leaders who resist what he perceives as EU appeasement and institutional bias against Zionist entity. Angela Merkel is acknowledged for Germany’s steadfast commitment to Zionist entity’s security, though her support is described as constrained by European bureaucratic pressures. Viktor Orban and certain Central European leaders are framed as part of a “new Europe” sceptical of supranational institutions and more receptive to Zionist entity’s security concerns, particularly regarding Islamicism and Iran.

A key theme in Bibi: My Story is Netanyahu’s deliberate pivot beyond traditional Western allies. Narendra Modi of India is portrayed as a transformative partner who abandoned India’s earlier public posture vis-a-vis Palestine in favour of strategic cooperation rooted in security and civilisational pride. Netanyahu frames Modi as a nationalist leader who, like himself, sought to overturn inherited diplomatic dogmas.

Similarly, Shinzo Abe of Japan is presented as a pragmatic ally who strengthened ties with Zionist entity as part of a broader strategic realignment.

Perhaps the most consequential category of leaders in Netanyahu’s memoir are the Arab signatories and architects of the Abraham Accords. Figures such as Mohammed bin Zayed of the UAE and Mohammed bin Salman of KSA are portrayed as visionary pragmatists who recognised Zionist entity as partner rather than enemy. Though not Zionists, they are implicitly framed as anti-Palestinian in strategic terms, having prioritised their interests over Palestinian demands. Husein bin Talal of Jordan is also remembered as a pragmatic survivor who valued stability and quiet cooperation with Zionist entity despite public tensions.

In stark contrast, Palestinian leaders — especially Mahmoud Abbas — are consistently depicted as doctrinal opponents who reject Zionist entity’s legitimacy and obstruct his pace. Netanyahu frames Palestinian leadership as intransigent, reinforcing his justification for bypassing them diplomatically. This portrayal underpins his broader strategy of pursuing regional normalisation without Palestinian participation.

Bibi: My Story presents a world divided not between left and right, but between strength and concession. Pro-Zionist leaders, in Netanyahu’s telling, are those who accept his security logic, challenge diplomatic orthodoxies, and marginalise the Palestinian issue as a precondition for peace. Anti-Palestinian positioning thus becomes synonymous with realism, while support for Palestinian claims is framed as naïveté or moral confusion. The memoir ultimately serves as both personal vindication and ideological manifesto, mapping a global alliance system anchored in power, nationalism, and Zionist self-assertion.

Sayeret Matkal and the fetishisation of the Commando

Netanyahu dedicates significant space to his time in Sayeret Matkal, the elite commando unit. He describes operations across the borders of Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria.

Through the lens of Fayez Sayegh and Walid Khalidi, these chapters read not as heroic adventure, but as the logbook of a trespasser. Netanyahu recounts crossing into sovereign Arab territories with impunity. This reflects the Zionist disregard for International Law regarding sovereignty, a concept central to the universalist critique. For Netanyahu, the “Law” is a tool for the weak. The strong make their own law.

Tony Judt famously critiqued Zionist entity’s reliance on military prowess instead of political legitimacy. Netanyahu’s memoir illustrates this perfectly. He derives his authority from his ability to wield the knife. He describes the “adrenaline” of combat, the “brotherhood” of the unit. It is a celebration of what Vladimir Jabotinsky called “Iron Wall” — the belief that Arabs must be crushed into submission before any dialogue can occur.

However, the memoir exposes a paradox. While Netanyahu celebrates the “daring” of the commando, Arendt’s concept of “Banality of Evil” suggests that true danger lies in thoughtlessness of the actor. Netanyahu describes the mechanics of raids — gear, timing, bullets — but never asks the political question: Why are we fighting? What is the root cause? He fights “terrorists,” never concerned if he is fighting the victims of his own entity’s 1948 ethnic cleansing (Nakba).

Diplomatic Debut: Weaponising Holocaust

Following his education and military service, Netanyahu enters the diplomatic arena as the Zionist entity’s Ambassador to the UN. This period marks the refinement of his rhetorical strategy, which Norman Finkelstein has termed “Holocaust Industry.”

This leads to the Second Key Exposure: strategy of equating Palestinian Liberation Movement with Nazism to bypass International Law.

Netanyahu recounts his speeches at the UN with immense pride. He details how he shifted the narrative from “Territory” to “Survival.” By framing the PLO not as a liberation movement but as the spiritual successors to the Nazis, Netanyahu effectively argues that Zionist entity is exempt from the laws of nations. You do not negotiate with Nazis; you destroy them. You do not apply the Geneva Conventions to the SS.

Primo Levi, a survivor of Auschwitz and a universalist humanist, warned against the misuse of the Holocaust memory. He feared it would be used to justify new oppressions. Netanyahu does the same. He weaponises the Holocaust to shut down debate. In the memoir, he dismisses the UN — the very institution avowedly established to prevent another Holocaust — as a “house of lies” because it dares to critique Zionist entity.

Moshe Zuckermann argues that this “Shoah-isation” of the conflict traps Zionist entity in a permanent state of victimhood. Netanyahu’s memoir shows he is the architect of this trap. He recounts showing foreign diplomats artefacts of Jewish history to prove “we were here first,” utilising a positivistic, archaeological nationalism that Shlomo Sand debunks. For Netanyahu, stones have more rights than the living Palestinians.

Oslo Years: Architecture of Obstruction

As the narrative moves into the 1990s and Oslo Accords, the urge of Netanyahu becomes acute.

Avi Shlaim, in ‘Iron Wall’, argues that the Zionist entity never intended to allow a Palestinian state. Netanyahu’s memoir confirms this with startling candour. He describes Oslo Accords as a national suicide note signed by “naive” ones like Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin.

He frames his opposition to Oslo through the lens of ‘Civilisational Alliance’. He argues that bringing Arafat to Gaza was importing a “Trojan Horse” of Islamo-fascism into the West. While Edward Said truly described Oslo as a surrender of Palestinian rights and saw the process as a restructuring of the occupation, Netanyahu, conversely, saw it as a surrender of Jewish land. Netanyahu reveals his role in the incitement against Rabin — though he fiercely denies the term “incitement” — by recounting the rallies at Zion Square. He portrays himself as the victim of a smear campaign following Rabin’s assassination. Amos Oz and David Grossman famously held Netanyahu morally accountable for creating the atmosphere of hate. Netanyahu’s defence is legalistic: “I never said to kill him” ; though as Arendt put it, a leader is responsible for the forces they unleash. Netanyahu unleashed the demon of ethno-religious nationalism to topple Oslo, and he refuses to acknowledge that demon.

The memoir exposes how he utilised the wave of Palestinian suicide bombings in the 1990s to destroy the Zionist ‘Left’. He reduced the complex equation of the occupation (oppression breeds resistance) to a simple binary: “They kill because they hate”, which is a causal factor in the hallmark of his ideology. Baruch Kimmerling called this “Politicide” — the denial of the Palestinian political existence.

By the end of the first third of the book, the reader encounters a fully formed Benjamin Netanyahu. He is a man armed with a “catastrophic” history inherited from his father, traumatised by the loss of his brother, trained in the arts of American public relations, and ideologically committed to the “Iron Wall.”

He has successfully constructed a worldview where Universalism is synonymous with weakness, International Law is a weapon of the enemy, and Human Rights are a luxury that the Jewish people cannot afford. He stands poised to take power, armed with the conviction that he alone sees the “truth” that the world — and the Zionist ‘Left’ — is too blind to see.

Netanyahu’s thinking is the thinking of 1948, of 1939, of 1492. It is a thinking of walls, trenches, and eternal war. “There is a way that seems right to a man, but its end is the way to death.” — Proverbs 14:12

Technocratic Occupation and Neoliberal Citadel

The narrative shifts from theoretical to operational. The aspiring guardian of the state becomes its architect.

This period, spans his first term as Prime Minister (1996–1999), his time as Finance Minister, and his return to power in 2009, represents the systematic dismantling of the “Hope” that briefly flickered during Oslo years. We see Netanyahu not merely as a politician seeking survival, but as a technician of what Giorgio Agamben termed as the “State of Exception.” He normalises a reality where the Palestinian is permanently suspended between life and death, stripped of rights, while the Zionist “Start-Up Nation” is hermetically sealed within a neoliberal bubble, insulated from the consequences of its own military footprint.

Wye River Deception: Performance of Peace

Netanyahu’s recounting of his first term, particularly the Wye River negotiations with Arafat and Clinton, serves as a masterclass in bad faith diplomacy. He portrays himself as a realist trapped in a room with dreamers and terrorists where he had gone not to implement Oslo; rather to suffocate it.

Netanyahu boasts of his “reciprocity” principle — “If they give, they will get; if they do not give, they will not get.” This soundbite masquerades as fairness, while stark power asymmetry was the ground reality. By demanding ‘security’ from a stateless authority (‘Palestinian Authority’) while simultaneously expanding settlements that undermined that ‘security’, Netanyahu engineered a failure.

He reveals a deep contempt for the “Peace Industry.” He views the American diplomatic corps not as neutral arbiters but as a naive bunch who believe that conflicts are misunderstandings. To Netanyahu, the conflict is a zero-sum game. He describes shaking Arafat’s hand with physical revulsion. For Netanyahu, Arafat has no face, only a target on his back.

Finance Minister: Neoliberalism as a Weapon of Separation

Perhaps the most self-congratulatory chapters of the book concern his tenure as Finance Minister (2003–2005). Netanyahu describes his slashing of the welfare state and his unleashment of free-market capitalism as the salvation of Zionist entity. He frames this through the Schumpeterian lens of “creative destruction.”

Netanyahu’s “Economic Peace” was never about uplifting Palestinians; it was about insulating the Zionist economy from the occupation. By integrating Zionist entity into the high-tech global market (“Start-Up Nation”), he severed the economic dependency Zionist entity once had on Palestinian labour. Netanyahu constructed a reality where Tel Aviv could boom while Gaza collapsed, and the average Zionist would feel no economic reverberation. He replaced the “Socialist Zionist” covenant (which, for all its exclusions, valued collective welfare) with a stark individualism. This eroded the internal Jewish solidarity that Martin Buber and early bi-nationalists hoped might eventually extend to their Arab neighbours. In Netanyahu’s neoliberal vision, there is no “society” — there are only consumers and soldiers.

Wall and Matrix of Control

He touches upon the construction of ‘Security Fence’ (in reality Apartheid Wall) during the Second Intifada. Netanyahu claims credit for pushing this barrier, framing it purely as a ‘counter-terrorism’ device. It created a vertical occupation — controlling the water below and the airspace above — while slicing the Palestinian territory into non-viable cantons.

Netanyahu’s narrative completely ignores the International Court of Justice’s 2004 advisory declaring the wall illegal where it cuts into the West Bank. This reinforces the theme established in Instalment I: International Law is a fiction to Netanyahu. His map is not drawn by the UN Charter; it is drawn by security needs and biblical claims. The wall allows the Zionist “Self” to look in the mirror and see only itself, blocking out the reflection of the suffering “Other” just meters away.

Bar-Ilan Speech: Empty Signifier

In 2009, under pressure from the Obama administration, Netanyahu delivered the Bar-Ilan speech, nominally accepting a “demilitarised Palestinian state.” In the book, he treats this speech as a tactical manoeuvre, a way to get the Americans off his back.

Netanyahu, here, used the word “State,” but he strips it of all meaning — no control over borders, airspace, electromagnetic spectrum, or alliances. It is sovereignty in name only.

This is the ultimate stabbing of the principle of self-determination. By offering a “state minus,” Netanyahu effectively codified the Bantustan model critiqued by Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela. He recounts this period with a smirk, proud of how he navigated the “trap” set by Obama. He sees the triumph of a delay tactic.

Obama Years: Clash of Paradigms

Conflict with Barack Obama takes up a massive portion of this narrative. Netanyahu frames this personal animosity as a clash of policies, but it is fundamentally a clash of cosmologies.

When Netanyahu recounts lecturing Obama in the Oval Office in 2011 — cameras rolling — he is performing for the “Base.” He is the defiant Jew refusing to bow to the Caesar of the West – the client state leader asserting dominance over the imperial patron to mask his deep dependency on that patron’s arms and veto power. Netanyahu portrays Obama’s desire for a settlement freeze as an obsession with “bricks and mortar.”

Perplexing Error

Netanyahu commits a fundamental historical error, betraying a striking lack of familiarity with early Arabian socio-religious realities, when he asserts: “The Kureish were a formidable Jewish tribe in Arabia. Unable to defeat them, Mohammed signed a peace deal with them. Once his force was strong enough, he abandoned the deal and destroyed the Jewish tribe.” (p. 290).

This claim collapses under even the most elementary historical scrutiny. It rests on categorical misidentification, anachronistic reasoning, and polemical reductionism, rather than on evidence-based historiography. Most notably, it conflates the Quraysh of Makkah — a predominantly polytheistic Arab mercantile confederation — with the Jewish tribes of Madinah, entities that were socially, geographically, religiously, and politically distinct. No credible historian has ever classified the Quraysh as a Jewish tribe. The “peace deal” invoked in this narrative can only plausibly refer to the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah (628 CE), concluded between Mohammed (SAAWS) and the Quraysh — not with any Jewish group. Far from being a ruse born of military weakness, the treaty represented a strategic and reciprocal diplomatic accord, acknowledged as binding by both parties. Its eventual collapse resulted from violations committed by Quraysh-allied tribes, not by Muslims — a fact documented in all historical sources. The subsequent entry into Makkah was marked by minimal violence and a general amnesty, rendering the accusation of treacherous annihilation historically untenable.

Relations between Prophet Mohammed (SAAWS) and the Jewish tribes of Madinah were governed by the Constitution of Madinah. This document explicitly affirmed Jews as a political community while guaranteeing full religious autonomy. Conflicts with specific tribes — viz. Banu Qaynuqa’, Banu Nadir, and Banu Quraydah — emerged within contexts involving treaty violations, military collusion with hostile forces, and acute internal security threats during an existential phase of Madinan state formation. Significantly, these measures were neither universal nor indiscriminate; Jewish individuals and communities continued to live in Arabia under Muslim rule.

Portraying these historically contingent events as acts of religious extermination implicitly celebrates treaty infidelity, yet another manifestation of his moral stance. Contemporary scholarship increasingly situates these episodes within frameworks of early state formation, wartime jurisprudence, and alliance politics, rather than confessional hostility.

The argument exemplifies how Islamophobic polemics substitute ideological conjecture for historical method, projecting modern moral binaries and conspiratorial intent onto a vastly different socio-political milieu. The grossly false claim that Prophet Mohammed (SAAWS) deceitfully destroyed a “formidable Jewish tribe” is not merely misleading; it is historically and historiographically indefensible and extremely ill-intentioned.

Iran Fixation: Great Diversion

Throughout the middle section, “Iranian Threat” rises like a monolith. Netanyahu compares Iran to Nazi Germany incessantly. The function of this threat in his narrative deserves scrutiny through the lens of Carl Schmitt’s Concept of the Political. Schmitt argued that a sovereign defines himself by his enemy. By elevating Iran to the status of an existential, cosmic evil (new Amalek), Netanyahu achieves two goals:

- Minimisation of Palestine: If the real threat is a nuclear Holocaust from Tehran, then the occupation of the West Bank is a trivial zoning dispute. The suffering of a Palestinian child in Hebron cannot compete with the spectre of a mushroom cloud over Tel Aviv.

- Permanent Emergency: It justifies permanent militarisation in the Zionist entity.

Netanyahu recounts his address to Congress in 2015 — bypassing the President — as a Churchillian moment. In reality, it was the moment he burned the bridge of bipartisan support to align Zionist entity fully with the forces of the American Right. He sacrificed the support of the Jewish Diaspora for the conditional love of Christian Evangelicals, whose support is based on eschatological fantasies rather than human rights.

By the end of this era, the “State Jew” has fully eclipsed the “Non-Jewish Jew.” Netanyahu has constructed a state that is economically robust, militarily formidable, and morally hollowed out.

He has replaced “Peace Process” with “Conflict Management.” He has replaced a narrative of integration with an architecture of segregation. He has convinced his people that they can live in a villa in the jungle, forever watching the “wild beasts” through the scope of a rifle.

Then, as the narrative moves toward Trump years and Abraham Accords, a new danger emerges – the fortress is so secure that the captain has begun to believe he is the state itself. The hubris of the “King of Israel” begins to rot the entity’s institutions from within.

Hubris of the Sovereign, Return of the Repressed

In the final third, the narrative undergoes a subtle but profound genre shift. It transitions from a political memoir to a hagiography of the self. Having convinced the reader of his ideological supremacy (Instalment I) and his technocratic indispensability (Instalment II), Benjamin Netanyahu moves forward to establish his ontological necessity. He is no longer just the Prime Minister; he is the avatar of the Nation.

This final era creates a claustrophobic political reality where the interests of the ‘State’ and the legal-political survival of one man become indistinguishable. Through the lens of Ernst Kantorowicz’s “King’s Two Bodies”, Netanyahu attempts to fuse his physical body (vulnerable to indictment, aging, and error) with the political body of the Zionist entity (eternal, sovereign, and immune) — a slide into what Jan-Werner Müller calls “exclusionary populism” — that “I alone represent the people” and implying that all opposition is illegitimate.

Trump Years: Simulacrum of Peace

The chapters detailing his relationship with Donald Trump are written with a sense of triumphant vindication. Netanyahu describes the moving of the US Embassy to Jerusalem and the recognition of sovereignty over the Golan Heights as historic corrections.

However, the centrepiece is the Abraham Accords. Netanyahu frames these normalisation deals with the UAE, Bahrain, and others as the ultimate refutation of the “Palestinian Veto.” He argues that he proved the world wrong: his objectives could be achieved without the Palestinians.

It was nothing more than a deal rooted in arms deals and surveillance technology (Pegasus diplomacy).

Netanyahu’s jubilation in these chapters exposes a fatal blindness. He believed he had successfully turned the Palestinian question into a “non-issue,” rendering the Palestinians as what Achille Mbembe terms a “surplus population” — invisible, managed, and contained. By celebrating deals that cemented the occupation, Netanyahu was pressurising the cooker.

Internal Enemy: War on Truth

As the narrative approaches the present day, the tone becomes increasingly paranoid. The corruption investigations (Case 1000, 2000, 4000) are dismissed by Netanyahu as a “witch hunt” and an “attempted coup” by the legal establishment.

Here, the book effectively declares war on the institutions of the Zionist state itself. The police, the prosecution, and the media are recast as the “Deep State” or the “Leftist Elites.” Hannah Arendt, in Truth and Politics, warned that the greatest danger of totalitarian thinking is not just the lie, but the destruction of the very capacity to distinguish between fact and fiction. Netanyahu’s memoir engages in this destruction. He portrays objective legal scrutiny as subjective political persecution.

By delegitimising his own entity’s judiciary, Netanyahu paves the way for the “Judicial Coup” of 2023 (which occurs after the book’s publication but is its logical conclusion). He breaks the social contract. He signals to his base that the Rule of Law is merely another tool of the “weak” — the “Non-Jewish Jews” in the Supreme Court — to shackle the “strong” national will.

Coalition of the Margins: Legitimisation of Kahanism

Perhaps the most glaring omission in the memoir is the cost of his political survival: the mainstreaming of Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich. To survive, Netanyahu had to invite the ideological heirs of Meir Kahane — whom the Zionist entity itself once designated as “terrorists” — into the cockpit of national leadership. A “Judeo-Nazi” phenomenon emerging from the occupation, this alliance shackled the ‘state’ to messianic fundamentalists who view conflict not just as strategic, but further as theological too.

Netanyahu presents his coalition building as masterful politicking — a Faustian bargain. By empowering those who openly advocate for expulsion and Jewish supremacy, Netanyahu stripped away the last veneer of Zionist entity’s “democratic” claim, exposing the ethno-nationalist core for the world to see.

Ghost Chapter: Collapse of the Conception (07.10.2023)

‘Bibi: My Story’ ends on a note of confidence, with Netanyahu poised to return to power, promising order and security. However, history has appended a horrific postscript that cannot be ignored. The events of October 7, 2023, serve as the unwritten “Ghost Chapter” that retroactively falsifies the entire thesis of the book.

The incidents of October 7, 2023 was the direct result of the “Conception” (Konseptzia) that Netanyahu champions in these pages: the belief that Palestinian resistance could be bought off with Qatari cash, that a high-tech wall could replace a political solution, and that the Palestinians could be “managed” indefinitely.

The “Iron Wall” that Jabotinsky theorised and Netanyahu built crumbled in hours. The high-tech sensors, the “Start-Up Nation” surveillance, and the military prowess were rendered useless by low-tech gliders and sheer human will.

This moment represents the “Return of the Repressed”. One could not imprison two million people in a “ghetto” (Gaza) for nearly two decades, bomb them periodically (“mowing the grass”), and expect eternal quiet. Netanyahu’s hubris — the belief that he could control the flames without getting burned — led the entity into its darkest hour. The memoir reads, in retrospect, not as a manual for victory, but as a logbook of Titanic’s captain, boasting about the ship’s unsinkability as he steers it into the ice.

Ruins of the Fortress

Closing ‘Bibi: My Story’, one is left with a portrait of a man of immense talent and intellect, corrupted by a fatal lack of empathy and a rigid adherence to a worldview that history has outpaced.

Netanyahu spent his life fighting the “Non-Jewish Jew” and sought to create a “New Jew”: a fortress, an iron wall, a sovereign power beholding to no one. He succeeded. He built that Jew. He built that ‘State’.

The result is a damage of biblical proportions. Zionist entity today, shaped in his image, is more isolated than ever, internally fractured, and locked in a cycle of violence. The surroundings have become an even worse place.

Albert Einstein and Hannah Arendt, in their 1948 letter, feared a Zionism that would divorce itself from the moral dictates of humanity. Benjamin Netanyahu’s autobiography is the documentation of that divorce. But as the smoke rises over Gaza and the kibbutzim of the south, the verdict of history suggests that the Fortress of Mirrors has shattered, leaving the inhabitants to face the terrifying reality of the world they created, but refused to see.

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. State of Exception. Translated by Kevin Attell, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Ahmad, Eqbal. Terrorism: Theirs and Ours. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2001.

- Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Viking Press, 1963.

- Arendt, Hannah. “Truth and Politics.” Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought. New York: Viking Press, 1968.

- Arendt, Hannah, Albert Einstein, et al. “New Palestine Party: Visit of Menachem Begin and Aims of Political Movement Discussed.” The New York Times, New York, 4 Dec. 1948, p. 4.

- Baron, Salo W. History and Jewish Historians: Essays and Addresses. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1964.

- Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? London: Verso, 2009.

- Chomsky, Noam. The Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinians. Boston: South End Press, 1983.

- Deutscher, Isaac. The Non-Jewish Jew and Other Essays. London: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by Richard Philcox, New York: Grove Press, 1963.

- Finkelstein, Norman G. The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering. London: Verso, 2000.

- Hazzard, Shirley. Countenance of Truth: The United Nations and the Waldheim Case. New York: Viking, 1990.

- Hever, Shir. The Political Economy of Israel’s Occupation: Repression Beyond Exploitation. London: Pluto Press, 2010.

- Judt, Tony. “Israel: The Alternative.” The New York Review of Books, New York, 23 Oct. 2003.

- Kantorowicz, Ernst H. The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Khalidi, Rashid. The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2020.

- Khalidi, Walid. All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992.

- Kimmerling, Baruch. Politicide: Ariel Sharon’s War Against the Palestinians. London: Verso, 2003.

- Klein, Naomi. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007.

- Leibowitz, Yeshayahu. Judaism, Human Values, and the Jewish State. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Levi, Primo. The Drowned and the Saved. New York: Summit Books, 1988.

- Levinas, Emmanuel. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Translated by Alphonso Lingis, Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1969.

- Mandel, Ernest. Late Capitalism. London: Verso, 1975.

- Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics. Translated by Steven Corcoran, Durham: Duke University Press, 2019.

- Netanyahu, Benjamin. Bibi: My Story. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2022.

- Pappe, Ilan. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2006.

- Rabkin, Yakov M. A Threat from Within: A Century of Jewish Opposition to Zionism. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2006.

- Rodinson, Maxime. Israel: A Colonial-Settler State? New York: Monad Press, 1973.

- Rose, Jacqueline. The Question of Zion. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Said, Edward W. The End of the Peace Process: Oslo and After. New York: Pantheon Books, 2000.

- Sand, Shlomo. The Invention of the Jewish People. London: Verso, 2009.

- Sayegh, Fayez A. Zionist Colonialism in Palestine. Beirut: Research Center, Palestine Liberation Organisation, 1965.

- Schmitt, Carl. The Concept of the Political. Translated by George Schwab, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Shlaim, Avi. The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2000.

- Weizman, Eyal. Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. London: Verso, 2007.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.