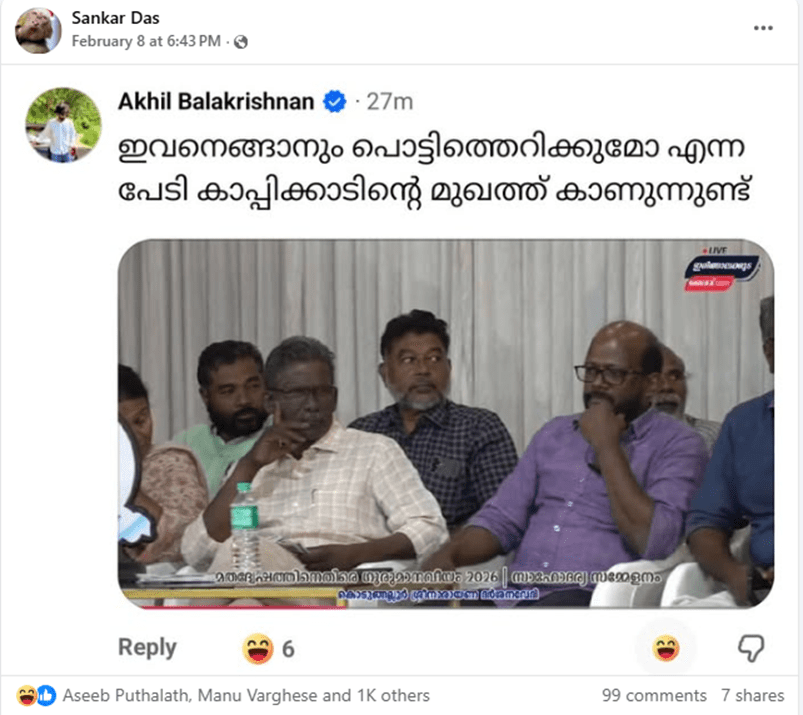

A meme that recently circulated across Kerala’s social media sphere is deceptively simple: journalist Dawood Chalikkal (commonly known as C Dawood) sitting beside noted Dalit intellectual and activist Sunny M. Kapikkadu at an event in Kodungallur commemorating the egalitarian ideals of Sree Narayana Guru. Yet, what transformed the photograph into viral fodder was not the event’s message of human equality but a meme authored by a self-described CPI(M) supporter- captioned as though Sunny were nervously wondering when this “Dawood guy” might “explode himself.” Celebrated across several left-affiliated “cyber-comrade” profiles, the meme condenses into a single image a deep-seated anxiety that has pervaded Kerala’s political imagination since the global “War on Terror.” The joke’s punchline rests entirely on the Muslim body coded as a potential explosive- an embodied sign of danger whose very presence is enough to unsettle the secular stage. It reveals not humor but the ordinary Islamophobia that now circulates freely between Hindutva and Left camps alike, exposing how both formations reproduce the same securitised gaze toward Muslim existence.

Some readers will be tempted to dismiss this argument as yet another instance of Muslims “playing the Islamophobia card,” a familiar accusation levelled whenever Islamic figures challenge dominant narratives. The script is well known: any objection to hate speech masquerading as “criticism” is framed as hypersensitivity, or as an attempt by so‑called “fundamentalists” to shield themselves from scrutiny by invoking the collective injury of “all Muslims.” This defensive move, however, is precisely what scholars like Mahmood Mamdani describe as the post‑9/11 sorting of Muslims into “good” and “bad” subjects of critique, where only those Muslims who accept their community’s criminalization are deemed reasonable participants in public debate. In such a landscape, a Muslim journalist like Dawood Chalikkal- who is also a member of the Jamaat‑e‑Islami Hind’s Kerala state council- does not enter the Kerala public sphere as a neutral professional but as a figure already overdetermined by suspicion, his political and theological affiliations read through the global grammar of “Islamism” and “terror.” By treating Dawood’s insistence on naming anti‑Muslim hostility as mere victimhood, Kerala’s commentariat reproduces what Ramon Grosfoguel[i] identifies as the coloniality of power: a system in which Western‑derived security discourse -war on terror, extremism, fanaticism -organizes which bodies are seen as legitimately political and which are imagined as permanent security risks.

It is against this broader architecture of Islamophobia that the recent targeting of Dawood Chalikkal must be understood, particularly after his prominent interventions on MediaOne TV’s daily news analysis program Out of Focus Dawood’s pointed criticism of the CPI(M)‑led LDF government’s attitude toward minorities, especially Muslims, coincides with growing public unease over the Home Ministry’s hostile posture toward Muslim‑populated regions and policing practices that disproportionately implicate Muslims in criminal cases such as gold smuggling, concerns sharpened by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan’s own comments associating ‘anti-Nationalism’ with the Muslim majority Malappuram district in an interview with The Hindu. These anxieties are echoed by figures like former Nilambur MLA P. V. Anvar, who broke with the ruling establishment while accusing senior officials of targeting “a particular community” through selective criminalization, thereby corroborating the patterns that Dawood and his colleagues bring to light in their broadcasts. Dawood’s editorial work, then, does not operate in a vacuum; it exposes how a state that presents itself as secular and progressive can nonetheless participate in what Mamdani[ii] calls the “securitization” of Muslim life, where entire districts and social spaces are governed under the sign of latent threat rather than equal citizenship. His presence on a channel like MediaOne- which itself has faced institutional pressure and hostility- renders him doubly suspect: as a Muslim journalist and as part of a media institution identified with Muslim community interests, he becomes a convenient figure onto whom the Left can displace its own anxieties about being accused of Islamophobia.

From the CPI(M)’s perspective, Dawood Chalikkal’s most unforgivable act is not personal antagonism but his sustained ideological audit of the party’s self‑image as the sole custodian of secular reason and subaltern interests. At the core of his critique is what he calls a political “double standard”: the party forges alliances with Muslim organizations at the national level to oppose the BJP, yet vilifies the very same formations within Kerala as “communal” when it needs to consolidate a Hindu‑majoritarian vote bank. In his analysis, this is not merely tactical inconsistency but a deep structural mirroring of the Sangh Parivar’s “minority‑hostile attitude,” in which Muslims are alternately instrumentalized and demonized depending on electoral expediency. This duplicity becomes starkly visible in controversies like the Nilambur by‑election and the party’s aggressive defense of leaders such as M. Swaraj, where any Muslim critique of Left governance is swiftly recoded as sectarian deviation. When Dawood unearthed the 1999 Assembly submission of former CPI(M) MLA N. Kannan- who spoke of the “Talibanisation” of Malappuram and alleged that Muslim shopkeepers were pressured not to sell black cloth to Sabarimala pilgrims- he highlighted how the party’s current denunciations of “communal propaganda” sit uneasily with its own historical record of pathologizing Muslim communities. Drawing on his long observation of the party’s persecution of dissenters like M. V. Raghavan, Dawood frames these episodes as evidence that the CPI(M) has hollowed out internal democracy and replaced class‑based organization with a sophisticated form of ethnicized dominance, particularly linked to Thiyya power in regions such as Nadapuram.

The party’s response to this intellectual and political challenge has been anything but subtle. In July 2025, during a CPI(M) Wandoor Area Committee protest against Dawood’s remarks referencing N. Kannan’s Assembly speech, party workers led slogans threatening to “cut off” his hand, a chilling invocation of bodily mutilation that was later formally distanced by state leaders but remained central to the public performance of rage. Journalists’ unions such as the Kerala Union of Working Journalists (KUWJ) condemned the protest as an assault on press freedom, while MediaOne lodged a police complaint detailing the abusive slogans and direct threats issued against its Managing Editor. Simultaneously, Dawood faced a deluge of cyber‑attacks and smear campaigns branding his analysis as “communal hate speech,” an attempt to invert the charge and position the Muslim critic as the real purveyor of bigotry. This pattern of “collective discipline and punishment”- mass mobilizations, threats of violence, calls for legal action- illustrates how a party that claims to uphold rational debate deploys what Mamdani would identify as sovereign power: the capacity to decide which voices may speak as legitimate critics and which must be neutralized as enemies of the political community. In Dawood’s reading, the hostility he faces is not an aberration but part of a longer global history in which communist parties, when confronted with internal dissent, have frequently opted for expulsion, vilification, or worse rather than allow alternative epistemologies to flourish.

Baburaj Bharagavathy’s reflections on the Dawood episode sharpen this contradiction. For him, the responses to the “cut off his hand” slogan reveal that freedom of expression in India is not a neutral, universal value but a concept structured by the power of the nation‑state and its dominant blocs. When Muslim organizations protest films like Vishwaroopam or burn copies of Mathrubhumi over blasphemy, the same secular commentariat rushes to declare a crisis of āviṣkāra svātantryam (freedom of expression), blaming “religion” for its suppression. Yet when CPI(M) activists publicly threaten a Muslim managing editor with amputation, the reaction is softened into the language of an unfortunate misstep, a stain on the party’s otherwise progressive record. In Baburaj’s reading, this asymmetry is not a mere double standard but a structural contradiction: Muslim experiences of injury are rarely admitted into the domain of “freedom of expression” and “media freedom.” The refusal to see Dawood’s case as a paradigmatic attack on expressive freedom is itself a symptom of Islamophobia.

If the Wandoor protest dramatized the bodily vulnerability of a Muslim journalist under Left rule, the statewide mobilization by the CPI(M)’s youth wing, the DYFI, across approximately 200 block centers marked the sheer scale of organizational power that can be marshalled against a single dissenting individual. The immediate pretext was Dawood’s commentary on Bhagat Singh, but he interprets the episode as symptomatic of a deeper intolerance toward challenges to the Left’s monopoly over historical memory and revolutionary symbolism. For Dawood, this is not just a dispute over a national icon; it is a struggle over what Sayyid terms “hegemonic narrations” of the political, wherein certain actors- here, the CPI(M) and its intellectual ecosystem- claim exclusive authority to define who counts as progressive, secular, or revolutionary. By deploying the DYFI’s vast network to stigmatize his interpretations as “communal” or “extremist,” the party constructs Dawood as a convenient Muslim “other” whose critique can be dismissed as identity‑driven, thereby shoring up its own claim to universal reason. In this sense, the protests function as a form of epistemic policing: they seek to enforce boundaries around legitimate knowledge of figures like Bhagat Singh, while disciplining those who insist on reading these icons through alternative ethical lenses. Dawood, by contrast, insists on his right to critique historical and political figures from his own ideological standpoint, refusing the demand that Muslims must either be silent or echo the Left’s script to be considered part of the enlightened public.

For writer Wahid Chullippara, the CPI(M)’s current ferocity toward Dawood Chalikkal cannot be understood apart from the party’s exposure in the so‑called “kafir screenshot” conspiracy around the Vadakara Lok Sabha campaign. Dawood was among the earliest to publicly state that the fabricated screenshot—framed as a communal appeal by a Congress‑affiliated Muslim youth leader urging voters to back a “true Muslim” against a “kafir (infidel) woman” (KK Shailaja)—originated not in Muslim League circles but within CPI(M)‑aligned cyber networks, a claim that subsequent police reports and media investigations have substantially corroborated. Wahid argues that what unsettles the party is not merely Dawood’s accusation, but the precision with which he situates this episode as part of a long‑term strategy in which the CPI(M) systematically manufactures and harvests Islamophobic fear to maintain its electoral base, making it easier for sections of its vote to drift toward the BJP when convenient. In his reading, this is a party that has rarely confronted questions of caste or Muslim marginalization from below, yet has no hesitation in donning a Hindu cultural common sense as its default idiom, even when performing “anti‑fascist” politics. The “kafir screenshot” becomes emblematic: a covert communal operation run from Left cyber cells, later disowned and redirected onto a Muslim scapegoat, in order to polarize constituencies while preserving the party’s secular halo. From this perspective, the vulgar social‑media campaign now unleashed against Dawood, and the studied silence of leaders like M. Swaraj -who otherwise lecture journalists on ethics- appear as acts of revenge by a party caught red‑handed in one of its dirtiest political maneuvers, lashing out at the journalist who refused to let the conspiracy pass as an electoral footnote.

Dawood’s own formulation of this conflict, articulated in a widely discussed interview with Samakalika Malayalam, cuts to the heart of the matter. Describing the CPI(M) as a party that claims “intellectual hegemony,” he portrays himself as someone who “wounds these dominant realms of knowledge,” and suggests that for the party, “ignorance” can function simultaneously as ornament and authority. This is an incisive way of naming what both Sayyid and Grosfoguel analyse as the coloniality of knowledge: a configuration in which certain epistemic communities -here, the secular‑Left intelligentsia- position their worldview as the only rational, scientific, and emancipatory standpoint, while relegating religiously grounded or minority‑located critiques to the realm of irrationality or communal passion. Dawood’s insistence that he is not habitually targeting the CPI(M), but rather scrutinizing those in power as part of his basic journalistic duty, is an attempt to reinsert himself into the category of legitimate critic rather than deviant Muslim subject. He frames his work as an audit of authority, not as partisan vendetta: if the CPI(M) is currently at the center of his analysis, it is because they control the state apparatus and must therefore be answerable to rigorous public questioning. In doing so, he exposes the asymmetry in how critique is racialized and religionized: when the party attacks Muslim organizations or media, it is cast as principled secular vigilance; when a Muslim journalist interrogates the party, he is rendered suspect, communal, or extremist. This double standard is precisely what a decolonial reading of Islamophobia urges us to see not as a series of unfortunate misunderstandings but as a structural pattern in which Muslim political speech is persistently de‑legitimized.

References

[i] Ramón Grosfoguel and Eric Mielants, “The Long‑Durée Entanglement Between Islamophobia and Racism in the Modern/Colonial Capitalist/Patriarchal World‑System,” Human Architecture 5(1), 2007.

[ii] Mahmood Mamdani, Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, the Cold War, and the Roots of Terror (Pantheon, 2004).

Salman Sayyid, Recalling the Caliphate: Decolonization and World Order (Hurst, 2014).

Salman Sayyid, “Answering the Muslim Question: The Politics of Muslims in Europe,” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology (or similar; open‑edition PDF).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.