Read the Part 1 here

In the previous article, we have mentioned that while studying the history of Bayt al-Maqdis, a consistent norm (Sunnah) of history is manifested to us, viz. Bayt al-Maqdis is like heart beneath ribs or a crown among cities and that it is not possible to reach it except through the surrounding capital cities. In the last article, we also discussed about the stages in the conquest of Jerusalem by Umar (RA) and its liberation by Salahuddin. From this, it must be clear that it is not possible to conquer Bayt al-Maqdis except after the conquest of Damascus and that it is not possible to liberate Bayt al-Maqdis except after purging Damascus and Cairo of the corrupt rulers. Liberation of Bayt al-Maqdis turns out to be just a matter of time, once Egypt and Levant are unified.

While the previous article dealt with its liberation, this article seeks to examine stages of the loss of Bayt al-Maqdis. of which there are three major ones – first crusade, sixth crusade and that done over a century now, ie., during the British occupation during its campaign against the Ottoman state after World War 1. During these stages of defeat, it was not possible for the enemies to reach Bayt al-Maqdis except through creation of turmoil, treachery or occupation of the two important capital cities around it, that is, Cairo and Damascus and during a later stage, Istanbul.

At the eve of first crusade, Egypt and Levant were divided. Egypt was under the rule of ‘Ubaydis (Fatimids) who were Ismaili Shiites and Levant was under Seljuks, who were Sunni. Levant itself was embroiled in a conflict between Seljuks and ‘Ubaydis. Both of these dominions had lost their powerful rulers. Seljuk rule had broken down in Levant after the demise of Malik Shah (d. 1092 AH, 485 CE), and ‘Ubaydi rule had entered into a particular phase called the era of the Viziers once their Caliphs became weak. The situation worsened further when ‘Ubaydis entered into alliance with the crusaders against Seljuks. Through this alliance, crusaders seized control and dominance over northern parts of Levant and soon after this they betrayed ‘Ubaydis and snatched Bayt al-Maqdis from them.

Thus, Bayt al-Maqdis was lost as the power capitals around it were in a miserable condition, with a weak Caliph in Baghdad, weak and quarrelling Seljuk rulers in Levant, and a weak ‘Ubaydi Caliph in Cairo. It was to remain for around 100 years under Crusader occupation which virtually turned Bayt al-Maqdis into a pig pen. The historical law mentioned in the beginning of this article appears in stark relief throughout the course of all subsequent crusade campaigns. Though the first crusader campaign succeeded in occupation of Bayt al-Maqdis, the second campaign came after liberation of al-Raha (Edessa) at the hands of Imad ad-Din Zengi. But, when this was achieved, Imad ad-Din had passed away and the matter was taken up after him by his son Nur ad-Din Mahmud, who allied with the ruler of Damascus. At that time, Damascus was in a truce with the crusaders, but the crusaders violated their treaty and attacked Damascus. This compelled Damascus to confront crusaders and this, besides other reasons, led to failure of the second campaign of crusaders.

The third crusader campaign came after liberation of Bayt al-Maqdis by Salahuddin. This was the biggest and fiercest crusader campaign. However, this came when Egypt and Levant were unified under Salahuddin. Thus, this enormous campaign failed and they were unable to occupy Bayt al-Maqdis. As for the fourth crusader campaign, its course was altered due to circumstances of internal European disputes. Thus, instead of coming to east it headed towards Byzantine Istanbul and seized it.

As for the fifth crusader campaign, it was one that affirmed the stark reality of the aforementioned historical law. The campaign was followed by a new thinking based on study of the previous campaigns. Accordingly, they identified the first necessary step as gaining control over Egypt. The lesson was clear – it would not be possible to seize Jerusalem and steadily maintain its possession without first controlling Egypt and seizing Cairo. Ibn Wasil gives an account of their mutual consultations as follows: “They convened to consult on what to start with, for the realisation of their objective. Intelligent ones among them pointed out that the first goal of crusader occupation should be occupation of Egypt.” Then they said:

“Salahuddin had control over the Mamluks, and managed to free Jerusalem and the coastal lands from Europeans only by virtue of his authority over Egypt, and he had strengthened himself through its men. Hence, it is in our interest to first aim for Egypt and possess it. Then there would not be any other hindrance for us in seizing al-Quds and other lands.” [1]

Unfortunately Salahuddin had passed away by then. His brother Saif ad-Din was also killed in an offensive launched by the Crusader campaign upon Damietta. Levant came under the rule of his son Eisa, and Egypt under his son Mohammad, also known as Kamil. In an incident with various powerful implications, al-Kamil proposed to the Crusaders that they should leave Egypt and in exchange he would hand over to them all cities that Salahuddin had liberated, including Bayt al-Maqdis, barring Karak and Shoubak castles. Crusaders were divided over this offer. Some of them agreed, seeing it as an invaluable opportunity. While others refused this and observed that it was not possible to guard the possession of Jerusalem without control over Egypt, and this latter opinion prevailed. Thus, Kamil had no option other than to resist the crusaders. After long battles his army and the armies of his two brothers who came to his aid were able to vanquish the fifth crusader campaign. It was within the reach of Kamil to annihilate the whole crusade army of this campaign, but because of his cowardly nature and weak character he refused to do so and allowed them to retreat unharmed.

It is worth noting here that al-Kamil’s policy and the crusader’s rejection of the offer made by him, affirms what that Cairo is a key to Bayt al-Maqdis and that, from a political and military perspective, it is more important than Bayt al-Maqdis ; though in terms of religion and sanctity, Jerusalem is undoubtedly far greater. However, balance of power is estimated in terms of resources and effective authority – wealth and men.

After this, it did not take much time for discord and differences to brew up among the three brothers – al-Kamil Muhammad of Egypt, his brother Eisa of Levant and al-Ashraf Musa of northern Iraq and al-Jazira (Kurdistan). Eisa allied with Jalal ad-Din al-Khwarizmi; and al-Kamil allied with Frederick II, of the Holy Roman Empire and it was to him that al-Kamil made the offer to relinquish Bayt al-Maqdis and all lands liberated by Salahuddin.

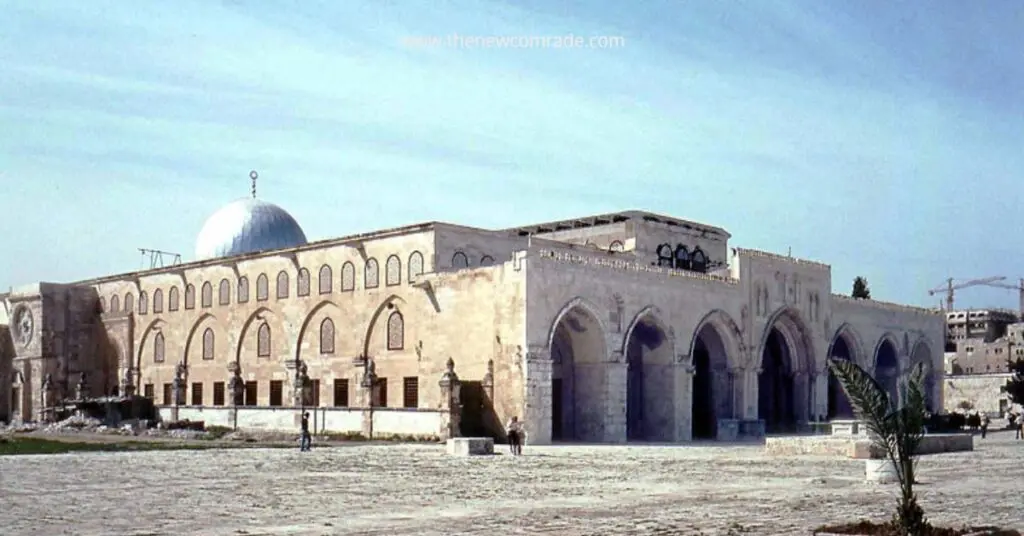

Eisa died in the year 624 AH, and al-Kamil took possession of his dominions. Also, Frederick was excommunicated by the Pope, and the crusaders in Levant opposed him and even offered al-Kamil to fight against Frederick, who had only a small number of knights (600) with him. Despite all this, al-Kamil handed him Jerusalem just to fulfil a promise and merely for the sake of alliance and friendship. Thus, Frederick accepted Bayt al-Maqdis with only six hundred knights and without any fight or loss of men, merely through negotiations. There were no gains for al-Kamil. This is one of the strangest stories of betrayal in history. Further, as a token of courtesy to Frederick, al-Kamil even prohibited the Muezzin of Bayt al-Maqdis from making the Azan. Al-Kamil informed his friend Frederick that he had imprisoned the leading Muslim religious scholars who had opposed the surrender of Bayt al-Maqdis. He even identified a scholar who issued a religious ruling permitting surrender of Bayt al-Maqdis to the crusaders. Al-Kamil imprisoned one of his army commanders, Saif al-Din Abi Zakri, who advised him: “Unite with your brother and nephew against this enemy so that it would not be said that the ruler gifted Jerusalem to the Europeans”[2]. After this, al-Kamil forcefully dispersed a sit-in protest near his tent, and they carried away the lamps and curtains of al-Aqsa.

After the death of al-Kamil, intense disputes ensued between the cousins, who inherited the mutual hostility of their fathers. There was constant shifting of battle lines between them. Ultimately their attitudes headed to the worse in a dramatically wretched manner. Despite this, Dawud, son of Eisa, was able to liberate Bayt al-Maqdis in 637 AH – though this was done merely to annoy his cousin Ayyub, son of al-Kamil then ruler of Egypt. In alliance with his uncle al-Saleh Ismail, he handed over Bayt al-Maqdis to the crusaders again in the year 641 AH. Further, al-Saleh Ismail promised the crusaders a part of Egypt in exchange of defeating Ayyub.

When these rulers handed over Jerusalem to the crusaders, they had made treaties with them to the effect that control of Bayt al-Maqdis would be retained by Muslims and status quo would be maintained. But the crusaders were least concerned in observing these pacts. Ibn Wasil, the historian, portrays the situation there:

“I entered Bayt al-Maqdis and saw monks and priests on the Noble Rock, and there were bottles of wine with sacrificial inscriptions upon them. When I entered Masjid al-Aqsa, there was a hanging bell. Azan and Iqama were prohibited there and disbelief was openly proclaimed” [3].

In the end, Ayyub of Egypt was able to crush his cousins and reunite Egypt and Levant. He allied with the Khwarizmids and succeeded in liberating Bayt al-Maqdis in 642 AH. This was after his victory in the Battle of Gaza over the alliance of his cousins and the crusaders. The historian, Sibṭ ibn al-Jawzī describes the scene of retreating army: “They all marched forth behind the flags of the crusaders, crosses being drawn on the heads of the Muslims with them and wine in their hands. [4]

Bayt al-Maqdis remained in the hands of Muslims until the English occupation, i.e, for seven centuries. During these seven centuries, Egypt and Levant were controlled by the same power – first under Mamluks and then under Ottomans. Bayt al-Maqdis, along with the two holy cities of Makkah & Madinah, were governed from Cairo and Damascus in the Mamluk era, Istanbul in the Ottoman era.

Once Istanbul was weakened and corruption afflicted it, the British were able to seize Cairo – the second most important city in the Ottoman empire after its capital, Istanbul. It was from Cairo that the British army which occupied Jerusalem had set out. This army had fought Ottomans in Levant and opened the way to occupy Jerusalem.

Prior to the British, a similar attempt was made by Napoleon Bonaparte. He occupied Cairo first and, from there, advanced with his army to Levant with the intention of occupying Bayt al-Maqdis, but the political situations were not favourable for accomplishing his mission.

The occupation of Bayt al-Maqdis took place thirty-five years after the occupation of Cairo. The British, exploited all resources available to them in Egypt, in terms of wealth, men, and even horses and donkeys that they usurped from the Egyptians for the purpose of this occupation and embarked upon World War 1 leading to fall of the Ottoman state and along with it the fall of Bayt al-Maqdis.

A cursory glance of the memoirs of Theodore Herzl, founder of the Zionist project, tells us about the same historical law. Herzl was extremely eager to establish a state for Zionists at Jerusalem by means of his influence upon the decisions of the important capitals that determined its destiny, be it directly, as is the case of Istanbul, or indirectly through capital cities like London, Berlin, Vatican, and Moscow – which would pressure Istanbul.

This discussion, God willingly, will be taken up in the subsequent article.

[1] Ibn Wasil, Mufarrij al-Kurub, 258/3

[2] Ibn Shaddad, al-A’laq al-Khatira, (History of Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine), p. 224

[3] Ibn Wasil, Mufarrij al-Kurub, 333/5

[4] Sibṭ ibn al-Jawzī, Mir’at al-Zaman, 381/22

Translated by- Thafasal Ijyas