From the beginning of the rise of the particularistic, appropriated form of Islam as represented by the early proto-Islamic groups, there existed a tension within the Sunni form of Islam: whether that of the immigrant Muslims or that of the Black American Sunni groups. The popular opinion as represented by the majority of Muslims- amongst a major portion naturally comprised of the Sunnis- does not recognize the members of Nation of Islam or Moorish Science Temple as Muslims, and they tried to place their Islam as authentic. While these immigrant Muslims were not a single, unified faction, a universalistic interpretation of Islam as contrary to the particularistic Islam disseminated by Noble Drew Ali and Elijah Muhammad, would contrast with the aforesaid appropriated form in various instances.

Most of the scholars who analyzed African-American Islamic thought have undoubtedly identified this tension, but not all of them have invented their own academic approach to address this tension. Fatimah McCloud, in her treatment of the history of African-American Islam, recognizes this tension as central to African-American Islamic thought and brings it to the position of a methodical assumption around which, the whole work revolves. McCloud analyses the aforementioned tension in African-American Islamic thought by employing the concepts of ‘asabiyyah’ and ‘ummah’- which were originally purported by the medieval Islamic scholar Ibn Khaldun- into the framework for African-American Islamic history1.

McCloud shows that this conflict occupies a position that is central to the rise and evolution of twentieth century African American Islam. McCloud’s assumption calls for the attention of scholars specialized in African-American Islamic history to give more importance to the issue related with this conflict as she did. This is what Damani Keita Davis seems to have in mind when she remarked McCloud’s work as “a final but important work.”2

Keita Davis would later explain this tension in her own words: “The conflict between these two positions are manifested in the continuous tension that has existed within the African-American Islamic movement, particularly between those that conform to orthodox standards and those that adhere Black-nationalist forms of Islamic expression. The former seeks to establish a unified Muslim identity with the global world of Islam, while the latter concentrates on the need for an empowered Black self-identity and community.”3

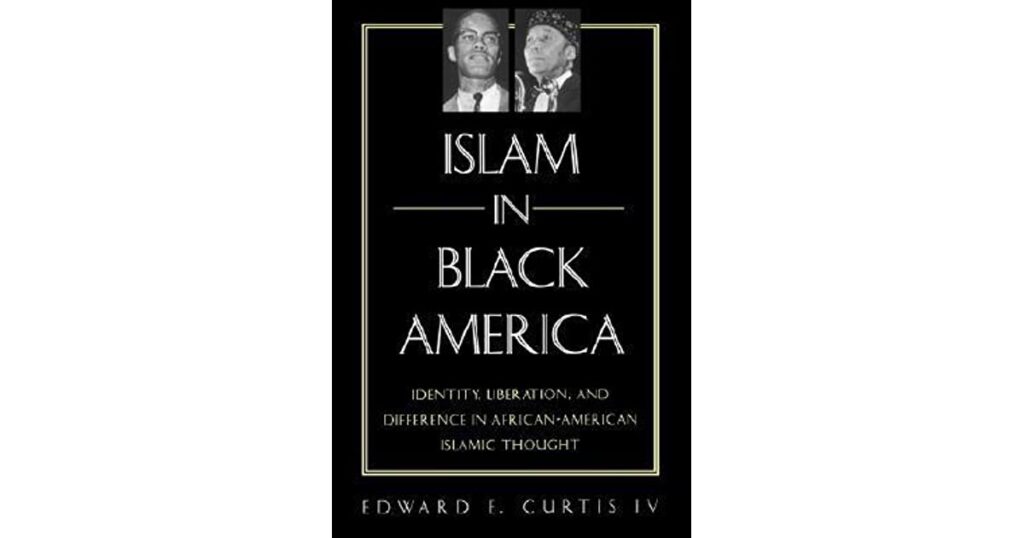

Edward Curtis places the beginning of this tension, or at least the existence of both of these contrasting impulses, to the beginning of African-American Islam itself.4 He identifies them as exactly ‘Universalism’ and ‘Particularism’ in African-American Islamic thought, which the primary focus of one of his works is.5 Curtis’ decision to identify this tension by these specific words came from his reading of African-American Islamic thought in relation to the particular socio-historical context this tension was seen. Since he understands the importance of the context in this historical study, his work naturally comes at the top level, in relation to its significance to this article.

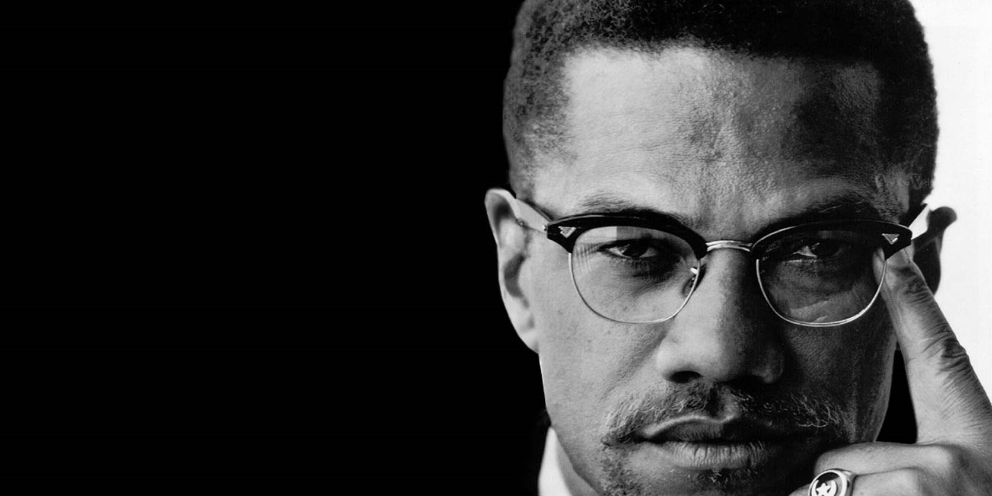

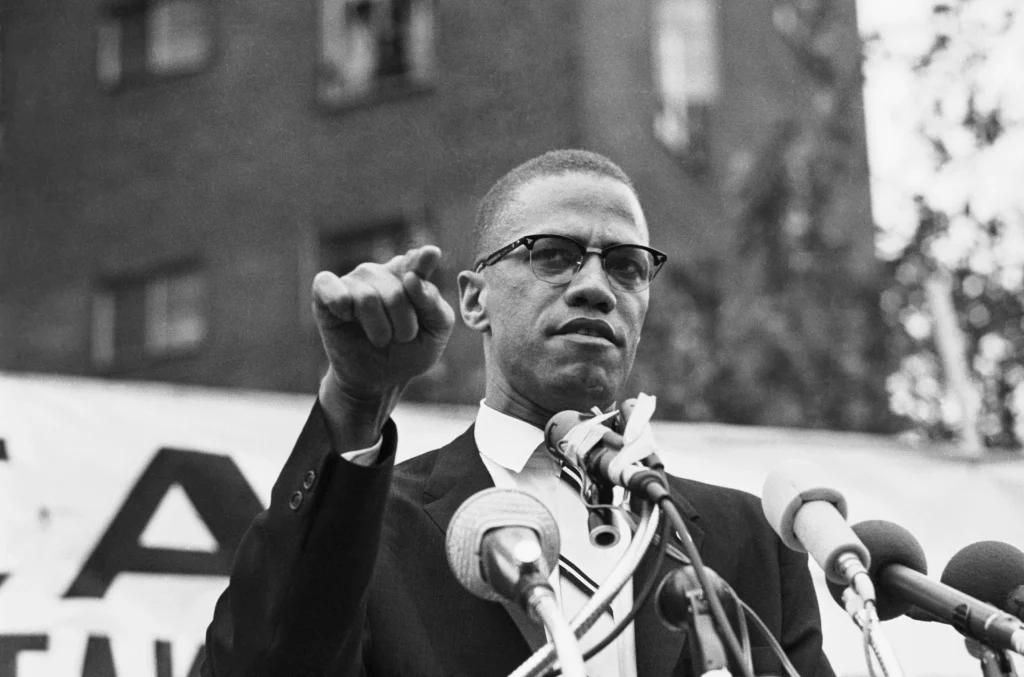

Whether it is McCloud or Curtis, or any others who identified this tension in African- American history, they all certainly note that this tension is more relevant in its influential capacity and is visible in the life of Malcolm X. Malcolm’s life is highly characterized by this tension. And it is the presence of this tension in Malcolm’s intellectual life and his actions, that constitutes a consequential role in making him one of the most controversial figures in the whole history of African-American Islam. Discussions and scholarly debates to understand Malcolm is a cumulative phenomenon. This article intends to put forth an idea: one possible way to understand Malcolm and his discourse, is to identify the play of aforesaid tension in his life and how he responded to it.

In the Hands of the Savior

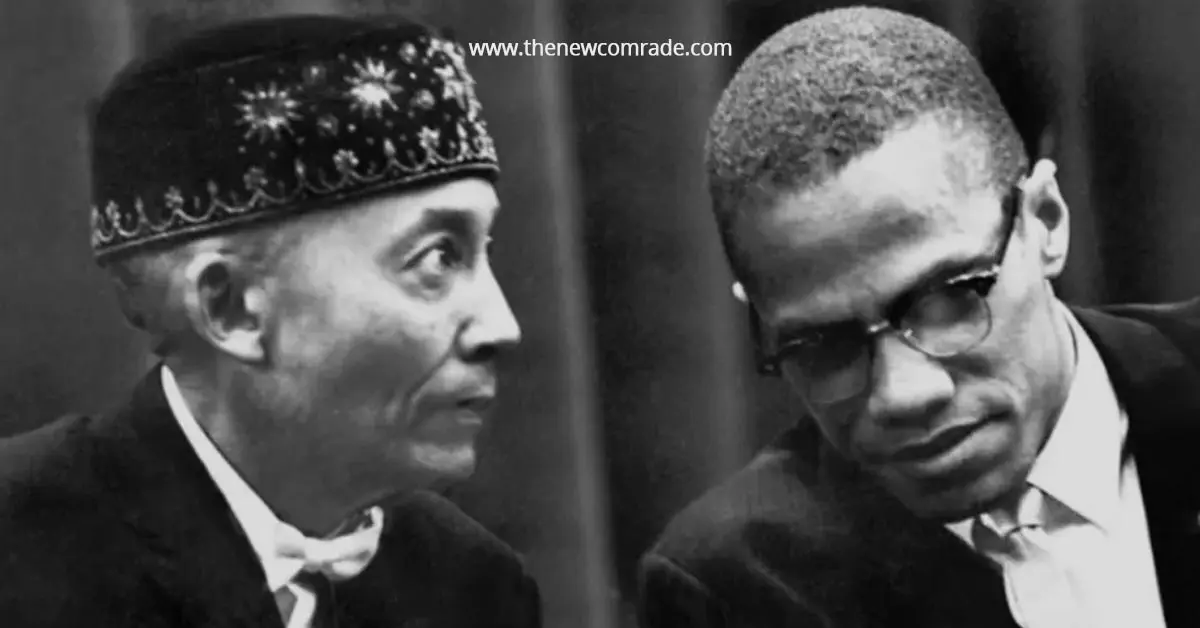

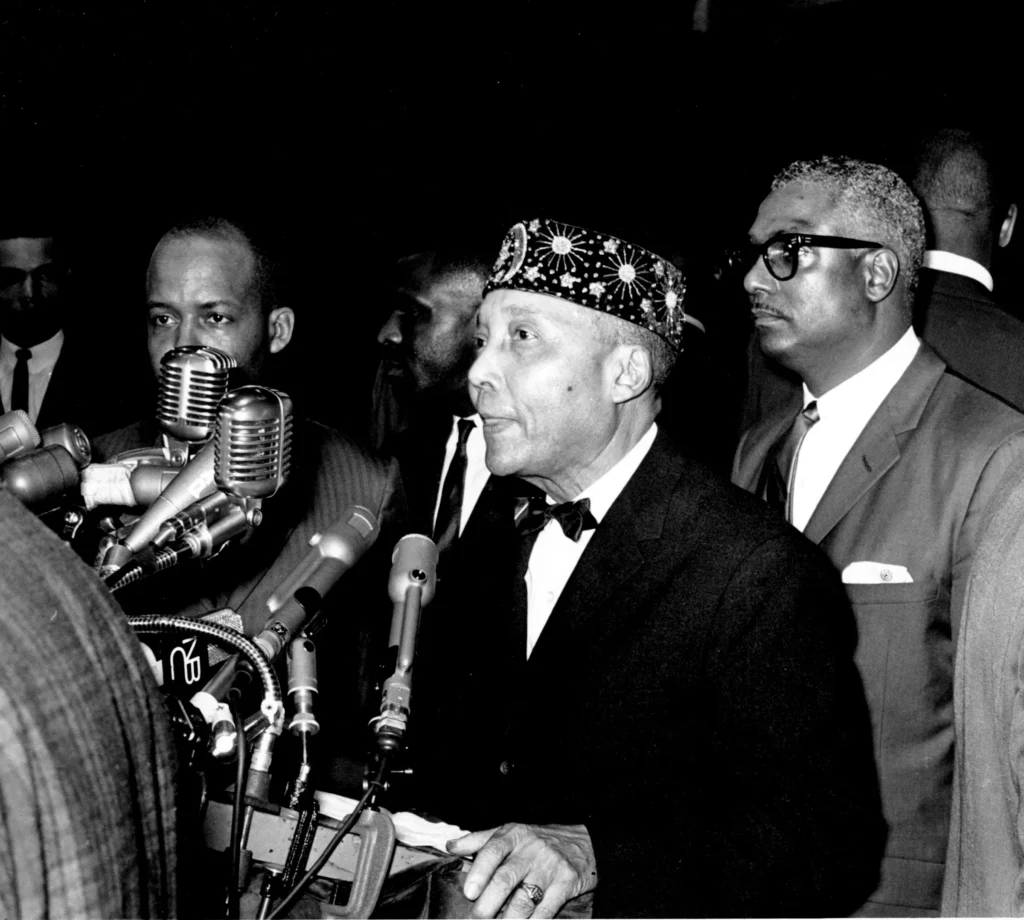

Adorning the position of the Prophet of the God in Flesh, Fard Muhammad, Elijah Muhammad posited himself as the only legitimate authority to interpret Islamic traditions. In the process of developing the particularistic Islam and the appropriation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad “had not only rejected Christianity, he had also rejected the right of anyone to interpret Islamic traditions except himself.”6 In doing so, Elijah Muhammad constructed an invisible barrier in the way of the aforementioned tensions and effectively obliterated any chances to be questioned. Commenting on Elijah Muhammad’s lack of expertise and scholarship in Sunni Islam, Curtis says: “By rejecting their challenges and offering his own interpretations of Islam, he effectively ended any possible debate and asserted his own prophetic authority. He embraced a particularistic form of Islam that he could control”.

As the sole authority to interpret this form of Islam rested with Elijah Muhammad, most of the followers adored him and his version of particularistic interpretation without any interrogations. These devotees were thankful for their “savior” who liberated their minds from the self-hatred and hopelessness that had entrapped them. It was in this particularistic Islam that these oppressed classes found solace and a sense of belonging. They were happy for the newly-found dignity and a religion that they could relate with a past of rich heritage that was exclusively their own. As such, most of them were not in a position to subvert this take or to question the Prophet, who himself was out

of question.

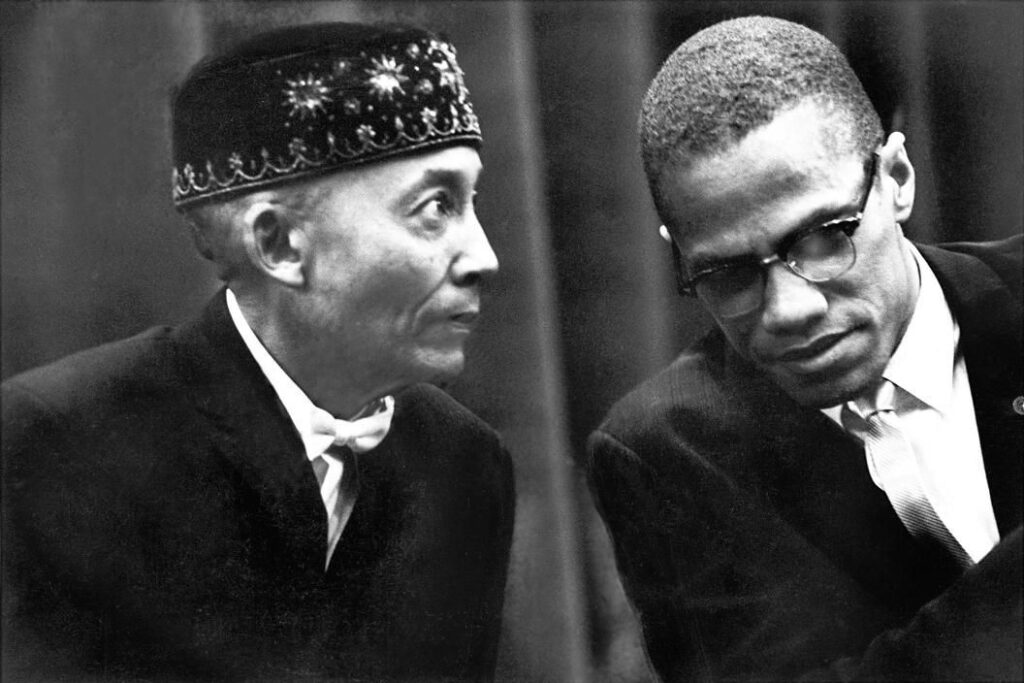

However, the existence of this tension would become too obvious to ignore that some would find themselves in positions to question Elijah Muhammad. Those who questioned the authority of Elijah Muhammad were more independent of him. One such follower who had identified himself as a devoted follower and expressed his deep commitment and loyalty towards his mentor and savior, but who would ironically become the carrier of this conflict or of these contrasting ideas in the very process of trying to avoid this conflict. This is what Curtis take in mind when he writes: “Malcolm confronted Muhammad’s critics on their own terms. That is, by trying to use Old World Islamic traditions to justify Muhammad’s beliefs. In so doing, however, he came to care far more about Muslims outside of the movement and about the traditions of Old World Islam.”

It is the writer’s contention that, this feature of Malcolm, to address or debate with seemingly contrasting ideologies and his willingness to present himself in a position which describes his ideas and standings wherever necessary, that would create diverse identities of Malcolm and his influences in people belonging to diverse social affiliations. As a result, many would easily misunderstand and miscalculate Malcolm and quote him in support of a variety of causes. “He is quoted as authoritative by sociologists and politicians. He is honored by black nationalists and white liberals. He is acclaimed by socialists, rightists and leftists. He is revered by Christians, Muslims and people with no religion at all.”7

Malcolm’s engagement with the proprietors of universalistic Islam would lead him to new horizons and would cause significant ramifications in his intellectual thought. This moment is highly important to the whole history of African-American Islam. While having the appearance of a devoted follower of Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm had always presented a keen mind in thinking and learning of different versions of Islam, even years before his split from the Nation of Islam.

There is scholarly consensus on the fact that Nation of Islam would not have achieved its level of success and popularity it came to enjoy if it wasn’t for Malcolm. This is a two-way bridge, since if it wasn’t for Elijah Muhammad and Nation of Islam, Malcolm would not have probably achieved his intellectual and social awareness and commitment. Malcolm would confirm this even during his later periods. In fact, this loyalty of Malcolm has always shadowed, at least in a minimal level, this conflict of particularistic and universalistic interpretations to engage in a more open level, and might have prolonged his separation from the Nation.

Whereas, it is not the intent of this article to provide a biographical sketch of Malcolm, it seems necessary to summarize at least some significant events in Malcolm’s life. Malcolm was born into a family, who were members of the UNIA of Marcus Garvey. White racist groups like the Ku Klux Khan and Black Legion had always haunted this family and in 1931, Malcolm’s father was killed in Michigan. For the next few years, Malcolm had to live in different foster care homes after his mother had finally given in to the psychological torture.8

The next significant period in Malcolm’s life was centred around Boston and New York, where he actively participated in the Black youth culture of the time. From 1940 to 1944, he followed his peers into hustling, drug racketing and pimping and made a reputation for himself, earning him many nicknames, Detroit Red being the prominent one. Malcolm, while remembering these times of his life for his autobiography, would say that he doesn’t intend to narrate any events from this period of his life to entertain the reader. It is clear that, just as his early encounters with the institutionalized anti-Black racism, these times would also contribute much to his persona and perceptions of the American reality. This period in Malcolm’s life have been subjected to scholarly studies in a distinct sense as different to other periods in his life.

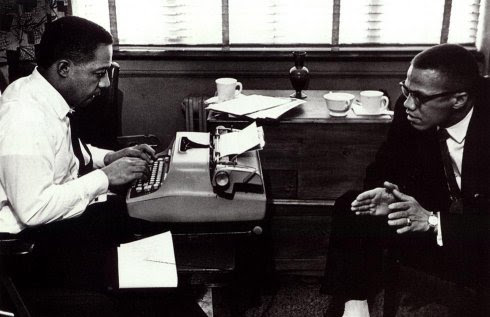

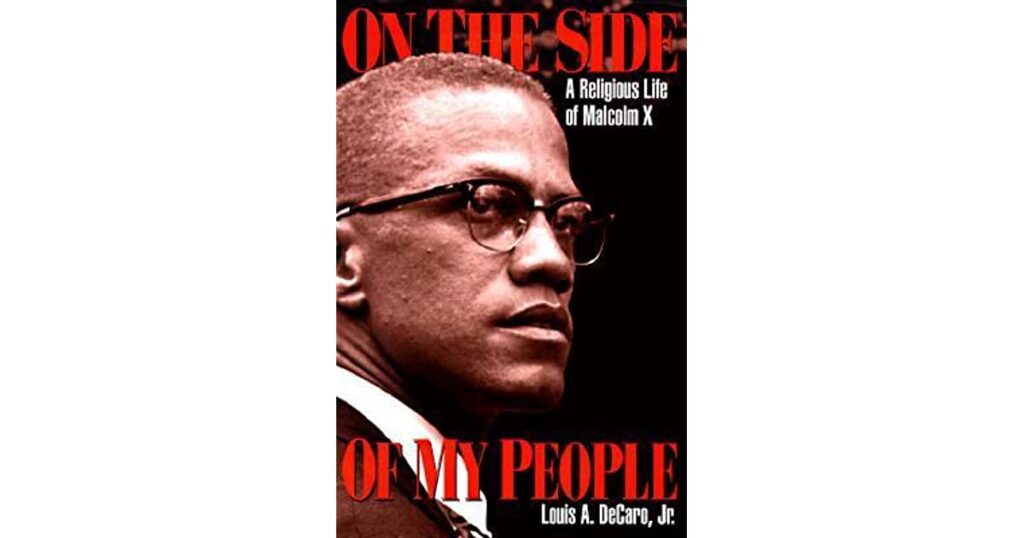

This period in Malcolm’s life came to an end when he was arrested for robbery and sentenced into prison in 1946. Manning Marable, in his controversial biography on Malcolm, analyses his imprisonment in relation to how his relationship with a White woman was a grave crime in the face of the Judiciary than the act of robbery itself.9 Malcolm would later acknowledge in his autobiography about how the convict “never will get completely over the memory of the bars.”10 It was during his stay in the Massachusetts state prison that he would go through the first conversion in his life. This conversion was the first in his life in relation to the conversions and intellectual developments that went through in the later periods of his life. Louis DeCaro’s work on the religious life of Malcolm is centered on the two major conversions in his life, the latter being his embracing of the orthodox or Sunni Islam. It would be through his brothers Reginald and Philbert Little that Malcolm come to know of Elijah Muhammad. This prison experience would bring about consequential psychological changes in Malcolm. Malcolm’s co-prisoner Jarvis would remark on Malcolm’s life in prison: “His extroverted life was taken completely away from him and his introvert part began to come forward. That’s what he used to tell us”. During this time, Malcolm started reading and made use of the prison library. He staunchly participated in debate clubs in the prison. Malcolm’s conversion to Nation of Islam and the ideas of Elijah Muhammad was a process that lasted months characterized by his intellectual activity in the prison and written exchanges with Elijah Muhammad himself.11

In 1952, Malcolm was released from prison. Without wasting further time, Malcolm met face-to-face with his mentor and joined the Nation. In 1953 Malcolm received the name ‘X’ from Elijah Muhammad, which he would carry with him until his death. He says in his autobiography: ‘For me, my “X” replaced the white slave master name of “Little” […]. The receipt of my “X” meant that forever after in the NOI, I would be known as Malcolm X’. Malcolm’s rise as a leader of Nation is rather dramatic. Fuelled by his intellectual experience from prison readings and speaking in debate clubs, Malcolm rose as a popular spokesperson and minister in the Nation in no time.

For the first 4 years, Malcolm formed and led temples in New York, Philadelphia and Boston. And in the following years, Malcolm would go through several instances that will bring the popular and FBI’s attention towards him. During this time, he spiritedly talked about integration and separation. By March 8, 1964, Malcolm was officially separated from the Nation of Islam. Some of the events that led to Malcolm’s split would be discussed in detail.

to be continued…

References

- Whereas Ibn Khaldun uses both of these terms in relation to interpret rise and fall of dynasties and groups in Islamic history, McCloud expertly incorporates the terms as that which pertain to different aspects of the “conception and constitution of community life.”

- Keita Davis, 16.

- Ibid, 17.

- Curtis, Islam and Black America, 15.

- Curtis explains this tension in his own words: “The tension exists between the idea, on the one hand, that a religious tradition is universally applicable to the experience of all human beings and the idea, on the other hand, that a religious tradition is applicable to the experience of one particular group of human beings”.

- Curtis, Islam and Black America, 83-4.

- Payne, 531.

- On this early period of Malcolm, see Malcolm X and Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Ballantine Books, 1987), 1–22. See also Carson, Malcolm X, 57–58; DeCaro, On the Side of My People, 38–43; and Wolfenstein, The Victims of Democracy, (Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 1981),42–152.

- 136Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. (New York: Viking, 2011)

- Malcolm X and Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Ballantine, 1992), 152.

- On this period in Malcolm’s life, see Malcolm X, Autobiography, 39–190; Kelly. Robin, Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class. ( Free Press, 1994)161–182; Carson, Malcolm X, 58–60; and DeCaro, On the Side of My People, 73–85.