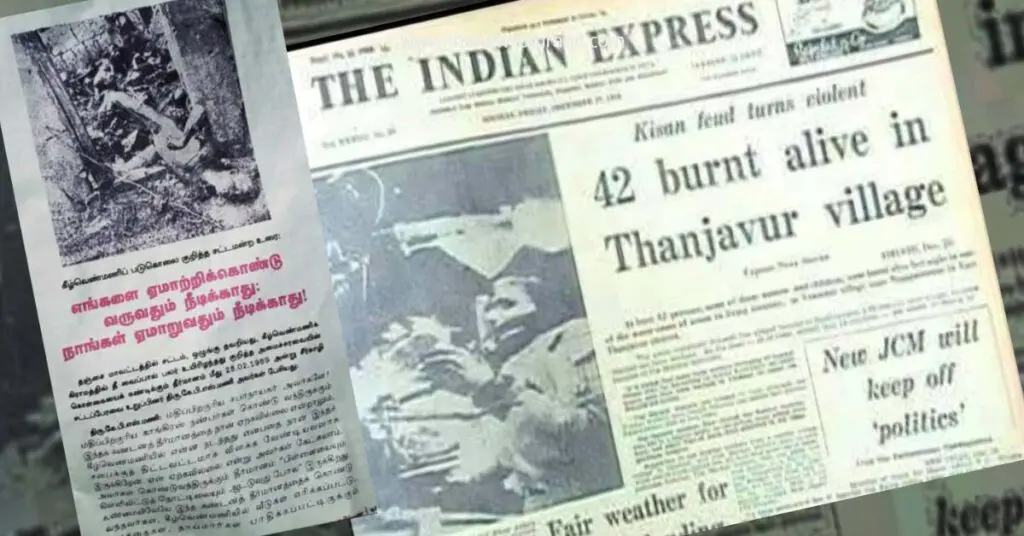

The Keezhvenmani massacre remains an indelible wound in the history of atrocities against Dalits in post-independence India. Also known as the Kilvenmani massacre, this tragic incident occurred in Kizhavenmani village, 8 km from Kilvelur, Nagapattinam District, Tamil Nadu, on December 25, 1968. During this event, 44 people, including 16 women and 24 children from Dalit agricultural families, were brutally burnt alive by landlords and their henchmen. However, it goes beyond being merely a class clash; politics and caste/class issues are deeply entwined in this historical tragedy.

As time has passed, inadequate documentation and conflicting narratives have shrouded the incident in mystery and uncertainty, making it increasingly challenging to discern the true details of what transpired.

The area was a major rice-producing region, with a significant portion of land owned by temple trusts. A small percentage of wealthy households controlled a large share of cultivated land, while a significant 41% of people were landless laborers, mainly belonging to the Dalit community (considered untouchables). Dalit laborers, often bonded, faced extreme poverty and discrimination.

The Communist movement gained momentum, leading to the abolition of the zamindari system and the introduction of protective acts like the Tanjore Pannaiyal Protection Act, 1952 (later repealed). In 1966, a spike in rice prices led Dalit laborers to demand better wages. The landowning class, fearing loss of control, formed the Paddy Producers Association (PPA) to counter Communist movements. The PPA resisted laborers’ demands and tried to coerce them into joining their union. When local laborers resisted, clashes ensued, resulting in the death of an outsider laborer and three members of the Communist Party-led Agricultural Workers Association.

Landlord Gopalakrishna Naidu, the mastermind behind the 44-farmer Keezhvenmani Massacre, openly threatened the village with arson during a PPA meeting in November 1968. The agricultural workers’ association sought protection from the Chief Minister, indicating escalating tensions.

According to eyewitnesses, on December 25, 1968, at around 10 pm, the landlords and their 200 henchmen arrived in police lorries and surrounded the hutments, cutting off all routes of escape. The attackers shot at the laborers, mortally wounding two of them. Laborers and their families could only throw stones to protect themselves or flee from the spot.

Many women, children, and some old men sought refuge in small huts. However, the attackers surrounded them and set fire to the huts, burning them alive. The fire was systematically stoked with hay and dry wood. Two children thrown out from the burning hut in the hope that they would survive were thrown back into the flames by the arsonists. Of the six people who managed to come out of the burning hut, two were caught, hacked to death, and thrown back into the flames. Shockingly, the attackers immediately walked to the police station and, to everyone’s dismay, their request was granted.

After the Keezhvenmani massacre, Chief Minister C. Annadurai sent ministers to the site, expressed condolences, and promised action. Landlords initially convicted in the event had their verdict overturned on appeal. Irinjur Gopalakrishnan Naidu, accused of orchestrating the massacre, was acquitted in 1975 but later murdered in 1980 in a revenge attack.

The situation hasn’t significantly improved. A 2016 report reveals a high number of cases under the Prevention of Atrocities Act against Dalits and Adivasis in Tamil Nadu. According to National Crime Bureau statistics, every day witnesses alarming incidents against Dalits—two houses burned, three women raped, two murders, and eleven beatings. What makes it worse is the understanding that only a tiny percentage of these crimes get officially recorded.

Remembering Keezhvenmani calls us to break the collective silence enabling prejudices against Dalits, from horrific violence to insidious daily injustices. The anniversary offers an opportunity to acknowledge oppression in all its forms, recognize its roots in an unjust social order, and take action against marginalization—whether through major events of the past or minor acts of bias still pervasive today. This solemn occasion must prompt society to check itself and resolve to speak out, so we may put an end to systemic oppression and secure justice.