1393 Ramadan War and dreams shattered- Memoirs of Refai Taha

Looking back at 1393 Ramadan (1973 October) war, I remember the first statement released by the command of the Egyptian military saying : “Aircraft of the Zionist enemy had struck our forces east and west of Suez canal. Our aircraft has repulsed this aggression and has driven them away from even above Sinai. ”

It seemed that they had begun to learn the art of framing statements that would look making military position appear legitimate and logical as arising from the right to self-defence. This formulation bore meaning that the matter began as defence but developed into chasing Zionist aircraft to the east of Suez canal over Sinai. After some time, came the second statement, talking about success of Egyptian forces in striking a blow to the enemy forces and that it was now in Sinai and has been able to cross Suez canal. This statement amounted to a declaration of war. It was this, which ignited the morale among the ranks of Egyptian populace. Thus public started raising slogans for Jerusalem and about their refusal to stop the war before liberation of Palestine.

Initially, this innate and spontaneous call spread among the people. It was as if there was a hidden feeling shared by all of them that this war may stop before liberation of Jerusalem. Perhaps, loss of trust of the Arab populace about their rulers had prompted them to not be convinced, even at the moment of war, that achievement of their goal would be pursued. Perhaps, this may have other explanations too – it gives room for sociologists and political psychologists to delve upon.

I found myself at the university with three or four students from different faculties – Sciences, Commerce and Engineering – for our induction. Together, we quickly agreed to organise a demonstration at the university the following day demanding persistence of that war. Though unforeseen, the war did persist. Thus, demonstrations demanding continuation of the war lost its relevance. People were wondering, what they could do further. It goes without saying that in the early hours popular upheaval had already done what was easily possible. People frenziedly flooded hospitals to donate their blood. The burning conscience that haunted those who did not participate in the war hastened them to ‘shed’ their blood – if it could be said so – in solidarity with those fighting the war in Sinai. Three days further, with the war continuing and people donating blood, ideas of volunteering in the war and assisting those fighting in the battlefronts propped up and became popular.

Despite all this, trust of people in the rulers was far from perfect. People were following news on foreign radio broadcasts from BBC, VOA and Monte Carlo, to affirm reality of Suez canal crossing and deployment claims of Egyptian army. Remains of the media deception of 1967 war was alive in the minds of the people. This time it seemed true. Egyptian forces claimed penetrating 10 km deep into eastern Sinai. Syrian army claimed to be advancing to liberate Golan heights. Reports indicated that the Egyptian forces were readying to continuing their advance into Mitla Pass!

Although Egyptian forces, as learnt later, did not plan to go beyond these 10 km, and originally, they did not plan to march onto Mitla pass. Foreign radio stations perhaps sought to provide grounds and impetus for armoured tanks battle that Zionists were mobilising for.

We later learn that while Egypt possessed less than four hundred tanks, media was galore about the largest tank battle, portraying a scenario of about a thousand Egyptian tanks facing a thousand Zionist tanks in Sinai. This gave greater impetus to the high morale of Egyptian people; to this, people added their own other exaggerations. This tank battle supposedly ends with capture of a Zionist commander, Assaf Yaguri, whose picture and picture of some of his soldiers were shown on newspapers and television screens in Egypt. Public morale soared ever higher, and convinced them that things were going well or even better than expected.

Many important specifics about this stage have fallen out from my memory. I could still affirm that public morale remained high until Sadat’s speech in the People’s Assembly on October 16, ten days after outbreak of the war, in which he raised the bogey of peace and, later, convened a peace conference. With this, public morale was broken. We entered a phase in which we began to hear people say : ‘We forfeit blood of the martyrs’ and similar expressions.

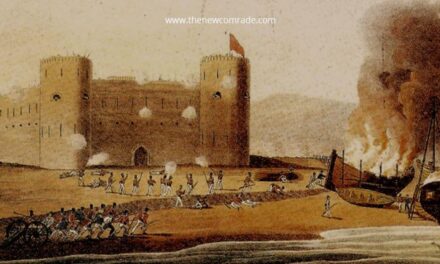

Within few hours after Sadat’s speech, news of the enemy breaching in began to leak out. Fighting had begun at the edge of Suez Canal. Hopes built up with earlier reports were dashed down. Radio stations were broadcasting news of Zionists invading Golan heights again. Balance of the battle were tilted. Zionists regained bridles of the battle. Then came the news of fighting in Suez. Television and radio stations reported that the then Prime Minister of the Zionist entity – Golda Meir – was visiting her forces on frontlines and declaring that she was fighting from the mainland of Africa!!

Sadat once again appeared before media and downplayed importance of the breach. Radio stations then reported that Egyptian forces were still present at the east of Suez canal in Sinai, but that there were also Zionist forces west of the canal. Egyptian army was no longer seen a victor with such a stalemate. Sadat justified this situation saying that it was a tactic and that what the Zionist forces achieved was not a strategic victory. He added that they were more besieged than the Egyptian forces, and thus it established superiority of the Egyptian forces.

However, statements issued by Egyptian military then were clear vacillator on those days – October 22, 23, and 24, corresponding to last days of Ramadan 1393. It was clear with the calls from various quarters for a ceasefire. Any person amongst us, during that period, could easily notice the state of panic in Egyptian media. I do not know if this was the general situation inside the army at that time. However, – as we learnt later – this had reflected on the ground situation as well. Zionist forces were able to advance on the Suez route and were able to besiege the Third Army in south-west Sinai. Egyptian regime expressed eagerness for a ceasefire, more than ever. Zionists had taken in the first blow and now regained control of the situation.

In addition to the collective psychological breakdown when ceasefire was accepted, details regarding differences in the army leadership leaked out – between Chief of Staff, Saadeddine Chadli, Minister of War, Ahmed Ismail and Sadat. From the moment of ceasefire, or even from the moment Sadat began talking about peace, opposition against him started to escalate. University campuses were one of the most important theatres that witnessed fierce opposition to Sadat.

The leftists led a massive campaign denying that Sadat was a war hero or even a peace hero, and that he only sold the cause to Americans. This statement was underpinned when Sadat later declared that 99 percent of game cards were in the hands of Americans. This was further corroborated when US President Richard Nixon, visited Cairo in the spring of 1974 CE. This visit reflected that Egypt had turned to the American camp and abandoned the Soviet camp.

Thus, the Ramadan war, that began with optimism, ended in a result that no one expected.

There are several questions raised in this regard: Was it, from the very outset, a war intended for a departure from particular political position, rather than being for liberation – as was claimed? Was this outcome pre-planned by senior political leaders? Or did it begin as a war of liberation and then end up with the afore-mentioned departure and closure of the file of supposed conflict with Zionists and opening the files of normalisation and surrender with it? All of these are left to the historians to ponder upon.

My admission to the University was in conjunction with this war. My days in the university were linked to the opposition that emerged throughout various universities against Sadat’s policy. This was a dramatic development for me – a departure from the era of Gamal Abdul Nasser during which opposition was dealt with extreme high-handedness even in a remote villages to an era in which opposition was tolerated in huge and central arenas.

This was accompanied by another dramatic development at my personal level. A son of a remote and obscure village found himself suddenly in a huge city like Asyut – it was something like a civilisational shock! This son of a small school with limited resources and subject to regulations found himself in an expansive university with lax rules and restrictions! This son of a smaller classroom found himself in a spacious and awesome auditorium! This student accustomed to dealing with teachers in school found another type of teacher, in personality, style as well as with the nature of a university professor! This son of a village, morally disciplined with gender segregation, encounters co-education, added to the absence of any parental control, something which, he had been long accustomed, to the extent of it becoming ingrained in his psyche.

Had it not been for the existence of “sections”, all resemblances between school and university would have been lost. These sections reminded us of the small classes of the school and the limited number of students therein.

I needed more time to understand this change in my life and to familiarise with this society that was totally new to my perceptions. However, life does not leave time for anyone – soon I entered fray in the initial days of university and found myself engaged in a clash with a law professor over Sharia.

[Refai Ahmed Taha Musa (also known as “Abu Yaser” and “Esam Ali”) was born in 1954 CE, he graduated from Asyut University (Faculty of Commerce). He was associated with the ruling Arab Socialist Union party of Gamal Abdul Nasser during while at school and transformed to Islamic activism during university days. He went on to become one of the founders of Gama’a el-Islamiya (Islamic Group – EIG). He spent considerable period in prisons of Anwar el Sadat & Hosni Mubarak and in various countries in exile. He was martyred in an American drone attack in Idlib, Syria in 2016, where he was involved in reconciliatory efforts between various revolutionary groups. He lived free in his native during the short-lived revolutionary period]

Compiled and edited by Mohammed Elhamy

Author Profile